A journey back in time to explore some the most iconic artworks of the ancients.

I recently wrote about some of the instruments that shaped humanity and realized that amidst the development of civilization, a core element of society was blooming. The birth of arts and culture among ancient civilizations was, to a large extent, linked to royalty, religious beliefs, and a growing concern for the afterlife. But many political and even provocative artworks were created in ancient times. Ancient art has had a profound impact on society.

I have always found art to be one of the most fascinating aspects of ancient culture. Join me on this art history tour as I travel, not just back in time, but around the world, as I explore some of the most notable artworks from the ancient world.

Dancing Girl

Our journey begins in the Bronze Age when a dazzling civilization was established along the basin of the Indus River between 7000 and 600 BCE. The Indus Valley Civilization was home to around five million people and spanned much of what is now South Asia.

The progressive society made impressive strides in technology and development. Among their many trades and talents were handicraft and metallurgy. This brings us to one of the largest settlements in the valley. Mohenjo-Daro, meaning “mound of the dead,” is now an important archaeological site in Pakistan. But in its heyday, it was a bustling metropolis making it one of the first major cities in the world.

Among the many notable artifacts found amidst its ruins was a unique bronze statue of a young woman. She has a thin physique, prominent facial features, and exceptionally long arms and legs. The nude girl is adorned only with a necklace and twenty-eight bangles donned in a curiously uneven fashion. And she appears to be clutching something in her left hand. But perhaps her most intriguing aspect is her confident yet almost nonchalant pose, which prompted the name Dancing Girl. It is unclear whether the depiction was indeed of a dancer. But musical instruments recovered from the region reveal a culture with an appreciation for the entertainment arts. Either way, Dancing Girl was an impressive find.

The captivating statue was sculpted using the lost-wax casting technique, and it exhibits a great deal of skill and fine craftsmanship. Dancing Girl is on display at the National Museum in New Delhi.

The Bust of Nefertiti

The name Nefertiti means “the beautiful one has come.” But the Great Royal Wife of the Pharaoh Akhenaten was likely more than just a pretty consort. Theories suggest that Nefertiti ruled as co-regent alongside Akhenaten and may have become a Pharaoh herself after his death. The royal couple reigned in one of the wealthiest and most influential periods in the history of Ancient Egypt. During their reign, they revolutionized the Egyptian belief system by switching from a polytheistic religion to the worship of the sun god, Aten.

The Bust of Nefertiti was the work of the renowned royal sculptor Thutmose. The limestone sculpture was coated in layers of stucco and finely painted in shades of blue, yellow, red, black, and white. The famously missing left eye sparked many debates and theories, but historians are still unclear why the left quartz inlay was never added.

The bust was discovered in the workshop of Thutmose along with several other similar unfinished works. But this was by far the most exquisite and perfectly captured the regal beauty and poise of the iconic queen. The nineteen-inch sculpture showcases immaculate craftsmanship, symmetry, and detail. And despite the chipped ears and a few nicks and cracks, it is one of the best-preserved artworks in Egyptian history.

The 3400-year-old sculpture is prominently displayed in a dedicated gallery at the Neues Museum in Berlin, where it is the leading attraction.

Nefertiti was the stepmother of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun, which brings us to the next Egyptian icon.

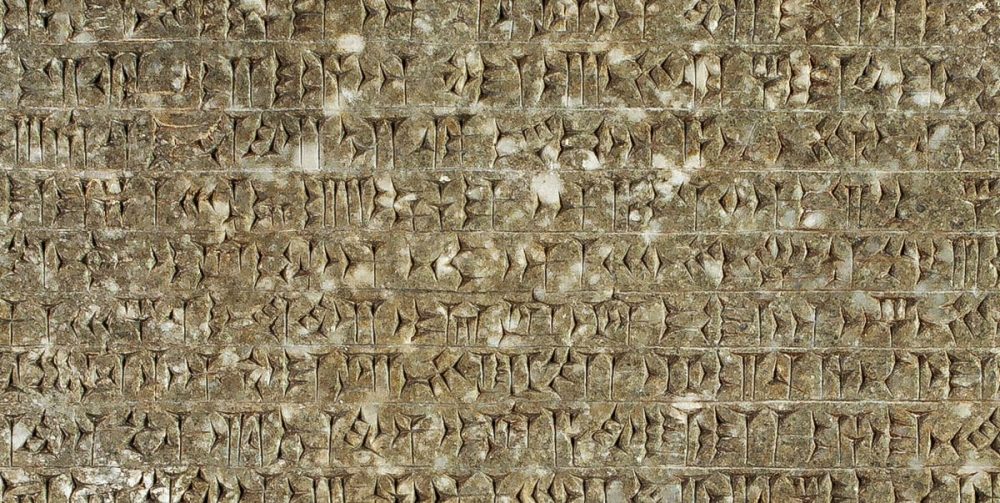

The Mask of Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun is one of the most notable figures of Ancient Egypt. Dubbed “the boy king,” he was only nine when he ascended the throne, and his reign was short-lived, as he died at the age of nineteen, circa 1327 BCE. Interestingly, the young King Tut abolished the monotheistic religion of his father during his reign.

The famous death mask is a trademark symbol of Ancient Egypt. Made of solid gold, the spectacular two-foot-tall artifact is embellished with lapis lazuli, turquoise, amazonite, and obsidian, among other semi-precious stones. The mask enhances the striking characteristics and adornments of the young Pharaoh, from the striped royal headdress and prominent facial features to the narrow, braided beard. Above the forehead are the protective goddesses Wadjet and Nekhbet, depicted by a cobra and vulture, respectively. A spell of protection from the famed Book of the Dead is inscribed on the back and shoulders.

The mask was crafted to resemble Osiris, the Egyptian god of the afterlife, based on the belief that kings preserved in his likeness would rule over the dead.

The Mask of Tutankhamun is one of Ancient Egypt’s greatest treasures. It is housed at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

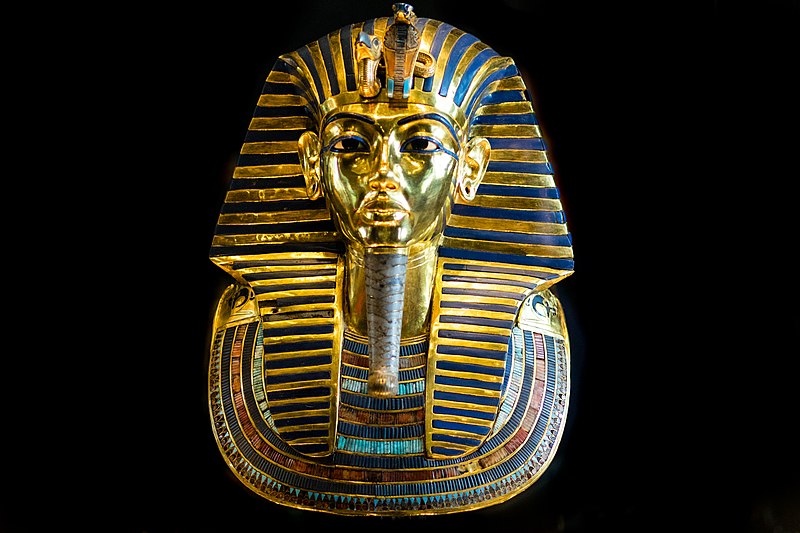

The Royal Standard of Ur

Our journey exploring the artworks of the ancients leads us to one of the greatest civilizations in history. Many Mesopotamian artworks exhibit cultural exchange between the great settlements. Of these, the wealthiest was the Sumerian city of Ur. Located along the Persian Gulf at the convergence of the Tigris and the Euphrates, Ur was an important trading point. It continued to thrive for Millenia, becoming a cultural hub during the Babylonian period before it fell into ruin around 450 BCE.

The ruins became an important archaeological site following the discovery of the Royal Tombs of Ur buried in the sands. Sixteen Kings and Queens were uncovered in the necropolis among a slew of extraordinary treasures, including the Royal Standard of Ur.

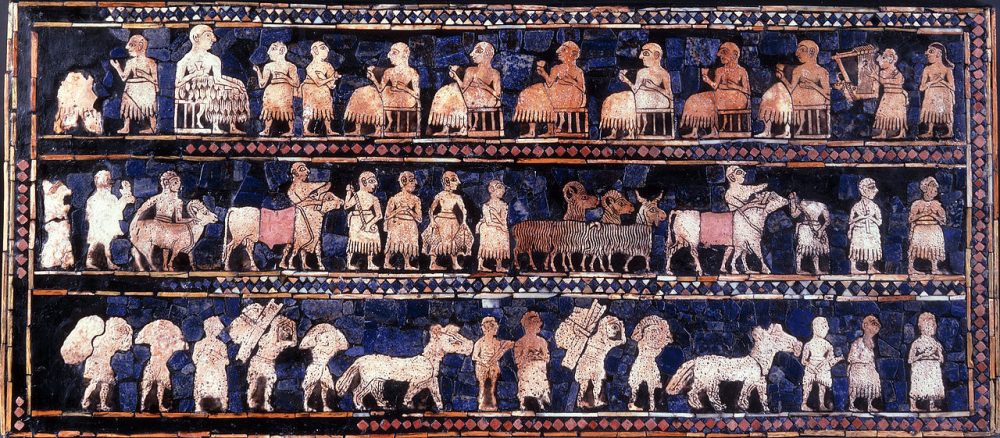

The exquisite twenty-inch artifact is made of wood and decorated in a fine mosaic of shell, lapis lazuli, and red limestone. Beyond the aesthetic appeal lies interesting insights into a rich culture and a chilling glance at Sumerian warfare. Its panels reflect stark contrasts. The “war” panel features brutal images of Sumerian military victory, where chariots trample enemy soldiers while others are killed or presented naked to a spear-wielding king. The “peace” panel depicts a merry banquet scene with drinking, music, and a procession bringing animals and other wares.

There have been many interpretations of the scenes depicted and whether they are connected or meant to illustrate concepts of duality. The artifact gives us a glimpse of a civilization with a vibrant culture and a macabre military code. The Royal Standard of Ur dates back to 2600 – 2400 BCE. It is now in the collection of the British Museum.

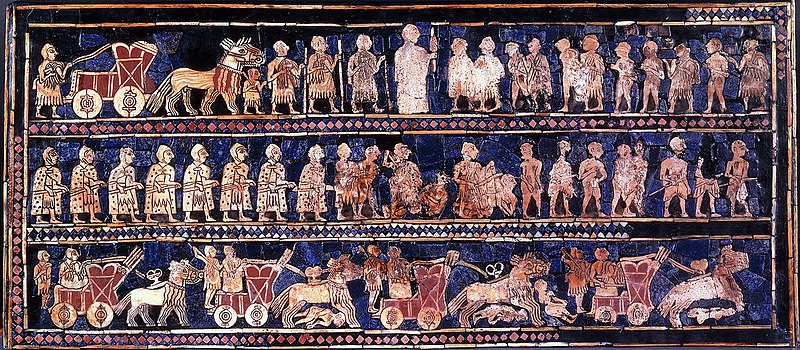

The Stele of Hammurabi

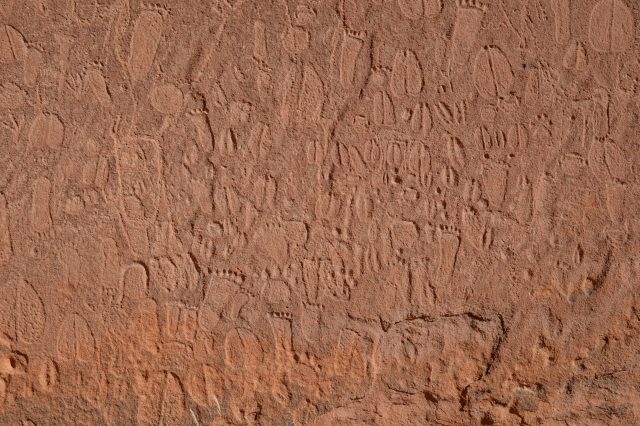

The Mesopotamians are renowned for some of the most notable modern advancements, including the invention of the wheel, the first writing system, and the first written laws. The Code of Hammurabi was one of the earliest legal codes in history and by far the best organized and preserved.

The code was proclaimed by the Babylonian King Hammurabi between 1755 and 1750 BCE. It was inscribed on a seven-foot-tall basalt stele in the shape of a finger. At the top of the stele is a relief carving of Hammurabi receiving the code from a seated Shamash – the Babylonian sun god who is also the god of justice. Beneath the relief, the comprehensive code is inscribed in cuneiform. The inscriptions include a poetic prologue, an epilogue, and 282 laws covering all aspects of Babylonian society, which was surprisingly complex. Although the code includes some brutal punishments, the laws are considered fair and admirable even by modern standards. It even mentions the principle of retribution, better understood as “an eye for an eye.”

Ironically, the Stele of Hammurabi was looted by Elamite invaders 600 years after its creation. It was rediscovered in 1901 and is now safely housed at the Louvre in Paris.

Winged Victory of Samothrace

We leave the cradle of civilization and head out into the Aegean Sea to the Greek Island of Samothrace, where the ruins of an ancient temple complex lie. It is known as the Sanctuary of the Great Gods. For over a thousand years, the initiates of a mystery religion worshipped secret deities and held ritualistic ceremonies at the enigmatic site.

The most notable artifact recovered from ruins was a statue depicting Nike – the Ancient Greek goddess of victory. She was found in three pieces and was missing a wing, along with her arms and head. The missing wing was reconstructed to match the other, but she remains headless and armless. Yet, Nike of Samothrace is considered the greatest masterpiece of its era and is one of the most celebrated sculptures in the world.

The 18-foot statue is believed to have been a tribute to the goddess and a commemoration of a triumphant battle at sea. Her original placement was at the bow of a ship set above an artificial lake. The draping garment hugs her body, sweeping around her legs as it appears to be blown by the wind. Her bold demeanor tells of victory as she balances to keep her composure against the gusts (Janson & Janson, 1962).

The breathtaking marble sculpture exhibits a mastery of form, motion, and dramatic realism. The use of such vivid imagery perfectly embodies the naturalist art movement of the Hellenistic period. But even beyond this, the Victory is one of the greatest works of art to emerge from the Greco-Roman era. The magnificent piece dates back to around 190 BCE and was likely sculpted by battle victors from Rhodes as a gesture to the Great Gods.

Today, the Winged Victory of Samothrace is triumphantly displayed at the top of the Daru staircase at the Louvre.

The Terracotta Army

In the year 246 BCE, Zhou Zen ascended the throne of the Qin State in a war-torn Ancient China at the age of thirteen. Soon after his ascension, hundreds of thousands of laborers were conscripted to build an elaborate necropolis for the young king, who would become the first emperor. Thirty-six years later, the Emperor Qin was buried along with a magnificent replica of his kingdom, complete with treasures, simulated skies and rivers, and the legendary terracotta army.

The life-sized figures vary in height, uniform, and hairstyle depending on rank. There are ten different facial shapes, with each face given individual characteristics. The figures were vibrantly painted in red, blue, green, purple, black, brown, and white. But the paint is believed to have flaked off within minutes of being exposed to the dry Xi’an air.

The army is in perfect military formation and includes chariots, horses, and over 7000 soldiers, most of which originally held real weapons. Interestingly, the figures were manufactured in workshops in an assembly-line fashion similar to modern factories.

The warriors are standing guard outside the tomb, which remains sealed for fear of booby traps and damage to the artifacts within. The stupendous mausoleum complex lies at the foot of Mount Li in the northeast of Xi’an. The Terracotta Army was created to protect the emperor in the afterlife and is one of the most exemplary forms of funerary art in history.

The Aztec Sunstone

Legend has it that our era began when the two gods Quetzalcóatl and Tezcatlipoca sacrificed themselves to create the sun and put it in motion. And to repay the sacrifices of gods, we must offer them sacrifices of our own.

This is one rendition of Aztec mythology pertaining to the origin of the universe. Our last stop is in the historical region of Mesoamerica, where an incredible civilization rose and fell.

It is believed that the Aztec Sunstone was used as a gladiatorial platform for human sacrifices. And it was likely for this reason that it was buried when the Aztec capital fell to Spanish conquerors. The iconic monolith was lost to the earth for two centuries before it was discovered during urban restoration works in 1790. The spectacular piece was originally part of the Templo Mayor. It is roughly 40-inches thick with a 12-foot diameter and weighs about 54-pounds. Its original coloration included bright red, turquoise blue, black, and white.

Carved out of basalt from the Xitle volcano, the intriguing artifact is a complex work of art shrouded in myth and legend. At its core is a record of the cosmic cycles and a cataclysmic history according to Mexica ideology. It depicts the eras, known by the Aztecs as the suns. The symbols illustrate the previous eras, as well as the current, which is believed to be the fifth era or the fifth “sun.” The glyphs on the sunstone indicate how the previous eras came to an end. The central figures form the shape of a glyph called an Olim, which means movement. From this stems the Aztec prophecy that our current era will end in a series of earthquakes.

The central figure is believed to either represent the sun god Tonatiuh, the night sun Yohualtonatiuh, or the earth monster Tlaltecuhtli. It has sinister, sunken eyes and a wide, open gape with its tongue sticking out in the form of a sacrificial knife, suggesting a hunger for sacrifice. On either side of the central figure are clawed hands, each clutching a heart.

The sunstone also bears twenty glyphs which represent the twenty Aztec days, which is why it is often referred to as the Calendar Stone.

The sunstone was created during the reign of the Aztec ruler Moctezuma, between 1503 to 1520 CE. It is the most recognizable work of art by any of the great civilizations of Mesoamerica. The Aztec Sunstone is proudly displayed at the National Anthropology Museum in Mexico.

Join the discussion and participate in awesome giveaways in our mobile Telegram group. Join Curiosmos on Telegram Today. t.me/Curiosmos

Sources:

- Mark, J. J. (2020, October 7). Indus Valley Civilization.

- Mark, J. J. (2014, April 14). Nefertiti.

- Mark, J. J. (2014, April 14). Tutankhamun.

- Mark, J. J. (2011, April 28). Ur.

- Mark, J. J. (2018, April 16). Hammurabi.

- Cummins, E. (n. d). Tutankhamun’s tomb (innermost coffin and death mask)

- Janson, H. W., Janson, A. F. (1995) History of Art. London. Thames & Hudson

- Cartwright, M. (2017, November 6). Terracotta Army.

- Cartwright, M. (2017, September 4). Sun Stone.