For the first time, astronomers have seen a black hole spewing stellar remains three years after consuming the star.

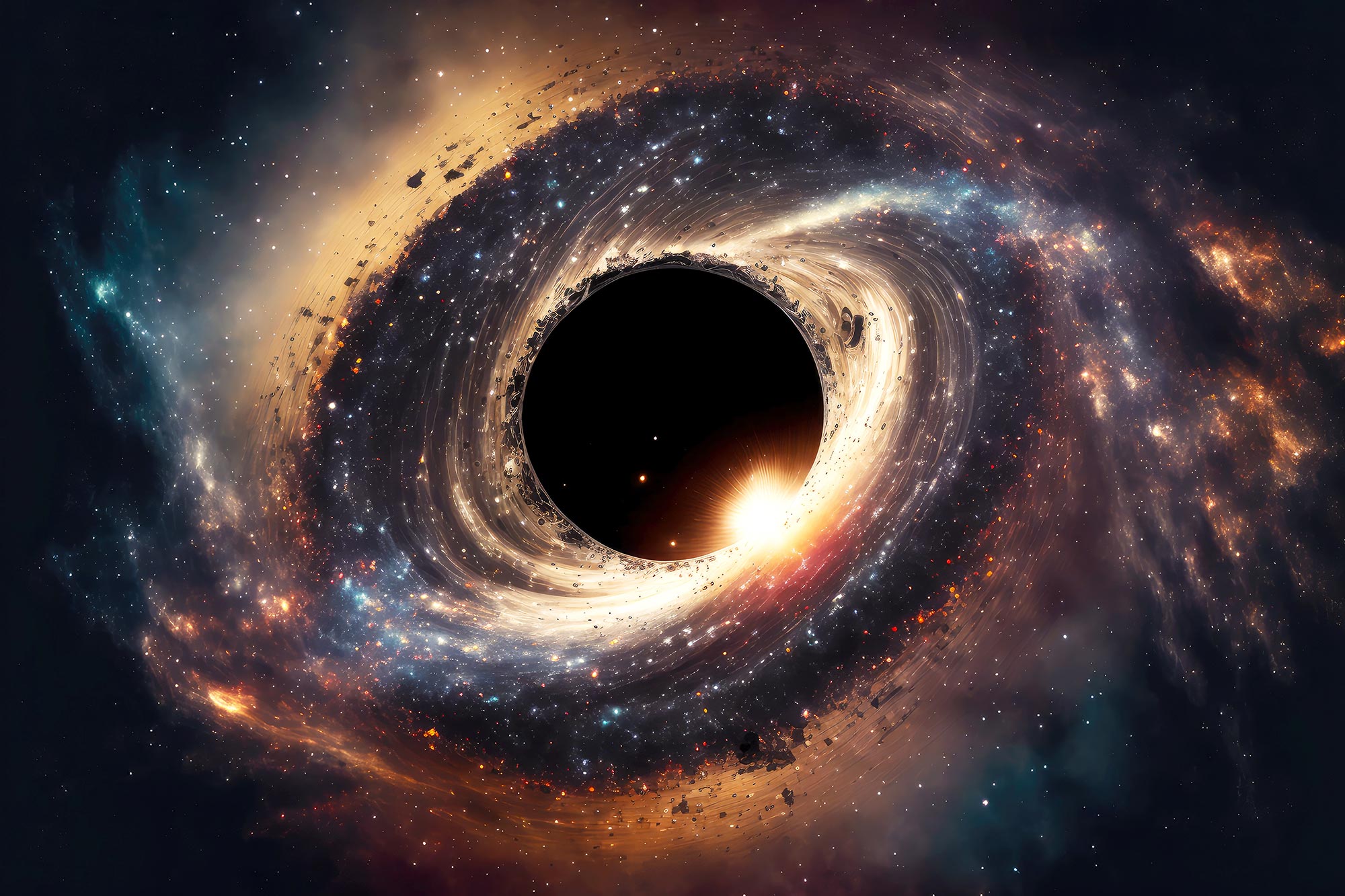

Four years ago, in October 2018, a small star came too close to a black hole located in a galaxy 665 million light years from Earth. It was literally shredded to pieces. As thrilling as it may sound, astronomers occasionally witness violent incidents while scanning the cosmos. So this event was not unexpected. However, what was unexpected was that a few years after the star had been “consumed,” the black hole started “throwing up” stellar fragments. In other words, the black hole was seen burping out parts of the star it had shredded to pieces.

“This was completely unexpected. No one had ever seen anything like this before,” said Yvette Cendes, a research associate at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian (CfA). In conclusion, the black hole is now ejecting material traveling at half the speed of light. However, the reason for the delay is unclear. Scientists may be able to better understand black holes’ feeding behavior by studying these results.

Tidal disruption events

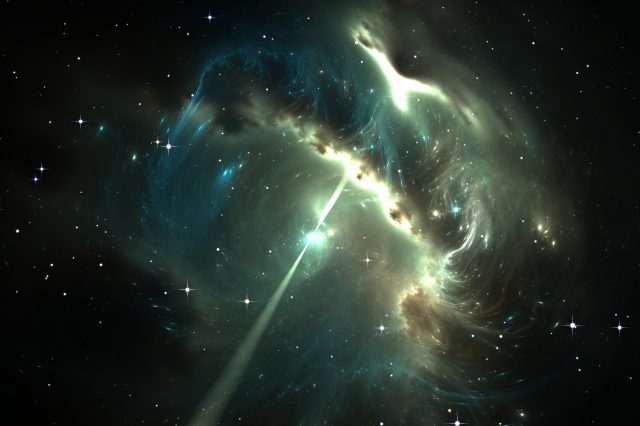

However, over the past several years, the team has observed several tidal disruption events (TDEs). This is when encroaching stars have been spaghettified by black holes. In June 2021, radio data from the Very Large Array (VLA) revealed the mysterious reanimation of the black hole. Immediately, Cendes and the team began examining the event more closely. It was so unexpected that scientists could not wait for the normal cycle of telescope proposals to observe it. They applied for Director’s Discretionary Time on multiple telescopes. “All the applications were accepted immediately,” Cendes said.

Through the VLA, the ALMA Observatory in Chile, MeerKAT in South Africa, the Australian Telescope Compact Array in Australia, and Chandra X-Ray Observatory and Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory in space, the team observed the TDE dubbed AT2018hyz at multiple wavelengths of light. The TDE was the most strikingly observed on radio. “We have been studying TDEs with radio telescopes for more than a decade, and we sometimes find they shine in radio waves as they spew out material while the star is first being consumed by the black hole,” says Edo Berger, professor of astronomy at Harvard University and the CfA, and co-author on the new study. “But in AT2018hyz, there was radio silence for the first three years. Now it’s dramatically lit up to become one of the most radio-luminous TDEs ever observed.”

Cosmic Spaghetti

When he first studied AT2018hyz in 2018 using visible light telescopes, including the 1.2-m telescope at the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory in Arizona, Sebastian Gomez, a postdoctoral fellow at the Space Telescope Science Institute and co-author on the research paper, said it seemed unremarkable. Gomez used theoretical models to calculate that the star torn apart by the black hole was only one-tenth the mass of our Sun.

“ AT2018hyz was monitored in visible light for several months until it faded away, and then it was forgotten,” Gomez said. The emission of light by TDEs is well known. Gravitational forces stretch stars near black holes, or spaghettified them. Astronomers can observe the flash from millions of light-years away. This is possible thanks to the spiraling material heating up around the black hole. Sometimes, spaghettified materials are flung into space again. In many ways, black holes resemble messy eaters – not all the food they consume makes it through their mouths.

Outflows, however, usually develop quickly after a TDE, not years later. “It’s like the black hole has just burped out a load of material it ate a long time ago,” Cendes explains. It is estimated that material is moving at a speed of 50% of the speed of light. Cendes says that most TDEs have outflows traveling at 10 percent of the speed of light. Berger says it’s the first time they have experienced such a long delay between feeding and outflowing. “The next step is to explore whether this actually happens more regularly, and we have simply not been looking at TDEs late enough in their evolution.”

Have something to add? Visit Curiosmos on Facebook. Join the discussion in our mobile Telegram group. Join Curiosmos on Telegram Today. t.me/Curiosmos