A groundbreaking study suggests that the key to unlocking the secrets of Earth’s earliest atmosphere may be found not on our planet, but on the moon. Lunar rocks, untouched for billions of years, could hold remnants of Earth’s ancient atmosphere, offering new insights into the early conditions of our planet’s formation.

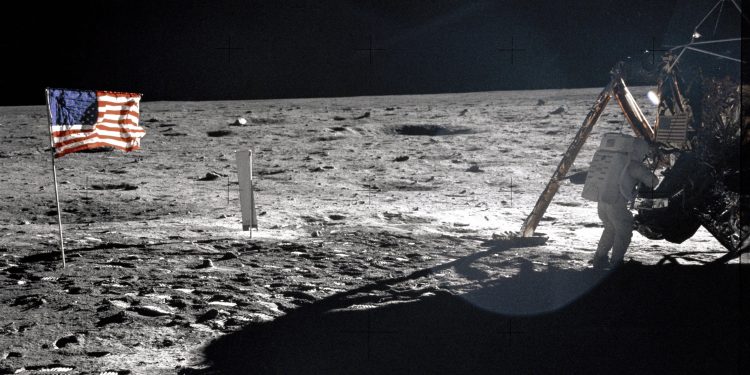

A recent analysis of Apollo mission moon rocks, brought back to Earth over 50 years ago, has revealed new clues about the moon’s past. Early studies had detected traces of magnetism within these rocks, suggesting that the moon may have once had a magnetic field similar to Earth’s. However, new findings indicate that the moon has been without a magnetic field for at least 4.36 billion years, according to the study’s co-author, John Tarduno, a professor at the University of Rochester.

This discovery is significant because, without a protective magnetic field, the moon may have absorbed particles from Earth’s atmosphere, potentially preserving a record of the Hadean eon, a period on Earth for which no direct geological evidence remains.

The Moon’s Quiet History: A Preserved Record

Unlike Earth, which has undergone billions of years of tectonic activity, the moon has remained geologically stable. As a result, layers of lunar regolith (the moon’s surface soil) may have remained undisturbed for billions of years. This geological stillness could provide an unprecedented window into Earth’s past. Tarduno explains that if scientists can locate a region of the moon with ancient regolith, it may hold the key to understanding Earth’s early atmosphere.

Finding this evidence would allow researchers to investigate the composition of Earth’s atmosphere as it existed 4.36 billion years ago—a time when no terrestrial rocks remain to offer clues. “We have no way of measuring the earliest atmosphere on Earth,” Tarduno notes, due to the planet’s active tectonic processes that have erased much of its early geological record.

Magnetic Fields and the Role of Lunar Rocks

Magnetic fields are typically generated by the movement of materials within a planetary body’s core. These fields protect planets from the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emitted by the sun. Certain minerals, particularly iron-bearing rocks, can record the orientation of a magnetic field when they cool and solidify, preserving a snapshot of the conditions at the time.

In their latest study, Tarduno and his team found that even lunar samples believed to be 4.36 billion years old show no signs of an ancient magnetic field. This finding builds on their 2021 research, which established that the moon’s magnetic field had already vanished by 3.9 billion years ago. These results suggest that any magnetization observed in the moon’s rocks may be the result of meteorite impacts rather than a planetary magnetic field.

Implications for Understanding Early Earth and Habitability

The significance of these findings extends beyond just Earth’s early atmosphere. The period in question—known as the Hadean eon—is largely a mystery. Earth’s early environment was far different from today, with a fainter sun and a potentially thick atmosphere of greenhouse gases that would have kept the planet warm enough to support liquid water and, eventually, life.

This ancient atmosphere might have resembled the thick haze seen on Saturn’s moon Titan today, according to Tarduno. This haze would have reflected sunlight, making it even more difficult for early Earth to heat up under the sun’s weaker rays. Understanding how our planet evolved under such conditions is crucial for exploring habitability on other planets.

Tarduno believes that by studying lunar rocks, we might finally gain the insights needed to understand not only Earth’s atmospheric evolution but also how similar processes might unfold on other planets. “If we can’t fully comprehend Earth’s past,” he reflects, “how can we make predictions about the evolution of other worlds?”