Astronomers are on the verge of exploring the atmospheres of Earth-sized exoplanets, thanks to groundbreaking advancements in observational techniques. In a surprising twist, Venus—our inhospitable planetary neighbor—may serve as the ideal testing ground for these methods, offering insights into worlds beyond our solar system. But how can scientists distinguish a Venus-like planet from an Earth-like one when viewed from light-years away?

A recent study led by the Institute of Astrophysics and Space Sciences (IA) tackled this very question by treating Venus as if it were an exoplanet. By analyzing rare data collected during the 2012 Venus transit across the Sun, researchers demonstrated that current techniques for studying large, hot exoplanets can also be adapted for smaller, rocky planets. The findings, published in Atmosphere, mark a major step forward in preparing for the next generation of astronomical instruments.

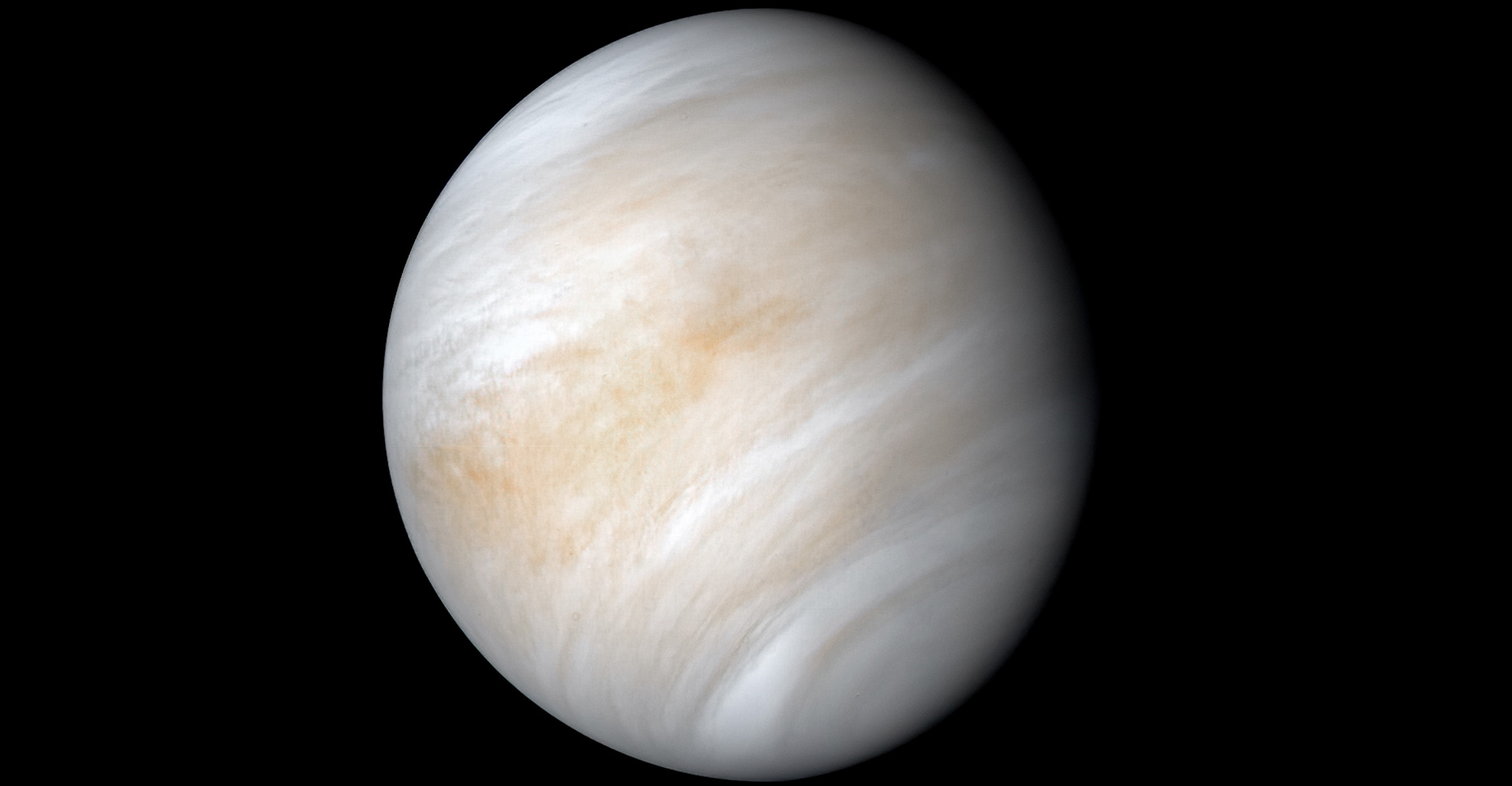

Venus as a Model for Exoplanet Exploration

Venus, though similar in size and density to Earth, has an atmosphere vastly different from our own. Its thick carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere traps heat, creating a greenhouse effect so extreme that its surface can melt lead. This makes it an ideal analog for the first Earth-sized exoplanets scientists are likely to study.

During the 2012 Venus transit, the planet passed directly in front of the Sun, allowing its atmosphere to leave detectable signatures on the sunlight that filtered through it. This technique mirrors how exoplanet atmospheres are studied when they transit their host stars. Molecules in a planet’s atmosphere imprint specific patterns on the starlight, revealing their chemical composition.

“Many of the small exoplanets we’ll study in the coming decades will orbit stars in environments similar to Venus,” says Alexandre Branco, lead author and MSc student at IA and the University of Lisbon. “This work is critical in adapting current techniques to probe these worlds effectively.”

The study confirmed that the methods used for giant exoplanets with hot atmospheres are effective for smaller planets like Venus. The researchers detected faint signatures of carbon dioxide in the data, validating the potential of this approach for distinguishing between planets with atmospheres like Earth’s and those resembling Venus.

Preparing for the Future of Exoplanet Discovery

This research also highlights the challenges of observing smaller exoplanets. Unlike the towering signals from gas giants, the atmospheric markers of rocky planets are subtler, often hidden in observational noise. Yet, upcoming telescopes such as the European Southern Observatory’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) and the European Space Agency’s Ariel mission are designed to meet this challenge. These tools will bring Earth-sized exoplanets within observational reach by the 2030s.

Pedro Machado, a researcher at IA and co-author of the study, emphasized the importance of this work: “The techniques we validated on Venus will directly inform how we study exoplanets. By using these methods, we’ll be able to detect minor chemical components and isotopic variations in planetary atmospheres.”

The study has far-reaching implications, not just for exoplanet science but also for studying planets within our solar system. Similar techniques are already being planned for observations of Jupiter and Saturn as bright stars pass behind them, allowing scientists to study their atmospheres with unprecedented detail.

This work also supports future missions like ESA’s EnVision, which will focus on understanding Venus’ atmospheric evolution. As Pedro Machado explains, “By studying isotopic changes and atmospheric chemistry, we can uncover Venus’ past and compare it to Earth’s history, offering clues about what makes a planet habitable—or hostile.”

As the search for habitable worlds intensifies, Venus provides an invaluable reference point. Its extreme environment offers a stark contrast to Earth’s, helping astronomers refine their techniques and distinguish between the two.

Join the Conversation!

Have something to share or discuss? Connect with us on Facebook and join like-minded explorers in our Telegram group. For the latest discoveries and insights, make sure to follow us on Google News.