Archaeological excavations at Tell Megiddo in Israel have revealed traces of a particular type of cranial surgery that took place around 3,500 years ago, making it the oldest such example found in the region. Moreover, the find may also represent one of the oldest examples of leprosy in the world, as explained by a research paper published in the journal PLoS ONE.

It is well known that ancient civilizations worldwide have practiced cranial trepanation for thousands of years. This medical procedure consists of drilling a hole into the skull. Trepanation is well documented as having been practiced in South America, Africa, Europe, and Asia. Some of the oldest evidence of this type of cranial surgery is believed to have taken place as early as 7,000 years ago in present-day Sudan.

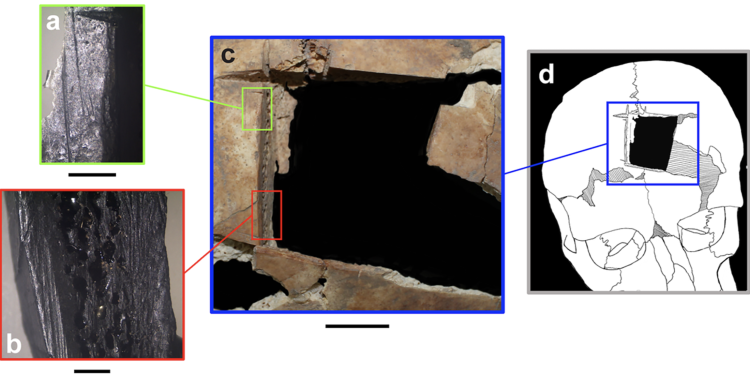

Thanks to recent excavation in the ancient city of Megiddo, there is new evidence that a particular type of trepanation dates back to at least the late Bronze Age. Scientists studied the remains of two upper-class individuals who lived in Megiddo around the 15th century B.C. and discovered that shortly before one of the individuals died, he underwent a specific type of cranial surgery.

Based on DNA testing, it turned out that the two individuals were related — they were brothers. Based on archeological studies, researchers believe that the individuals who lived between 1550 B.C. and 1450 B.C. suffered from different chronic diseases, and one of the brothers underwent ancient brain surgery just before he died. And although such surgeries are found to have taken place around the world, there is rarely evidence of trepanation in the Middle East.

The brothers, who were buried beneath the floor of their family home in the wealthy bronze city, likely held a higher social status that allowed them access to medicine less fortunate people had not. Although they suffered from different diseases, their social status allowed them access to treatments that were otherwise unavailable. But despite their wealth, not even state-of-the-art medicine of the time could help them. According to initial studies, one brother died in his late teens or early twenties and was buried one to three years before the other. The other brother succumbed after the unsuccessful surgery and is believed to have died between the age of 21 to 23. Eventually, the younger brother was exhumed so the two could be buried together.

As explained by the Smithsonian, both siblings suffered from several diseases. Their skeletons, for example, show signs of congenital anomalies. The brother who underwent cranial surgery suffered from a condition in which the bones didn’t fuse together normally during infancy. Furthermore, scientists say that both brothers’ bones show signs of infectious lesions of a disease that was most likely leprosy. The many lesions on the skeletons suggest that both siblings likely lived with various diseases for extended periods of time.

PLEASE READ: Have something to add? Visit Curiosmos on Facebook. Join the discussion in our mobile Telegram group. Also, follow us on Google News. Interesting in history, mysteries, and more? Visit Ancient Library’s Telegram group and become part of an exclusive group.