In a groundbreaking analysis of Martian soil, scientists have discovered the longest organic molecules ever detected on the Red Planet—carbon chains that resemble molecular structures associated with biological activity on Earth. Found in 3.7-billion-year-old clay samples inside Gale Crater, these molecules could reshape the way researchers investigate Mars’s early chemistry and its potential to host life.

The discovery, led by researchers from CNRS in collaboration with teams from France, the United States, Mexico, and Spain, will be published on March 24, 2025, in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (here and here).

What makes this find different?

Organic molecules containing up to 12 carbon atoms in a row were identified—far longer than any previously confirmed on Mars. On Earth, such structures can form through both biological and non-biological processes. However, the presence of these stable, preserved molecules in Mars’s clay-rich terrain is especially compelling.

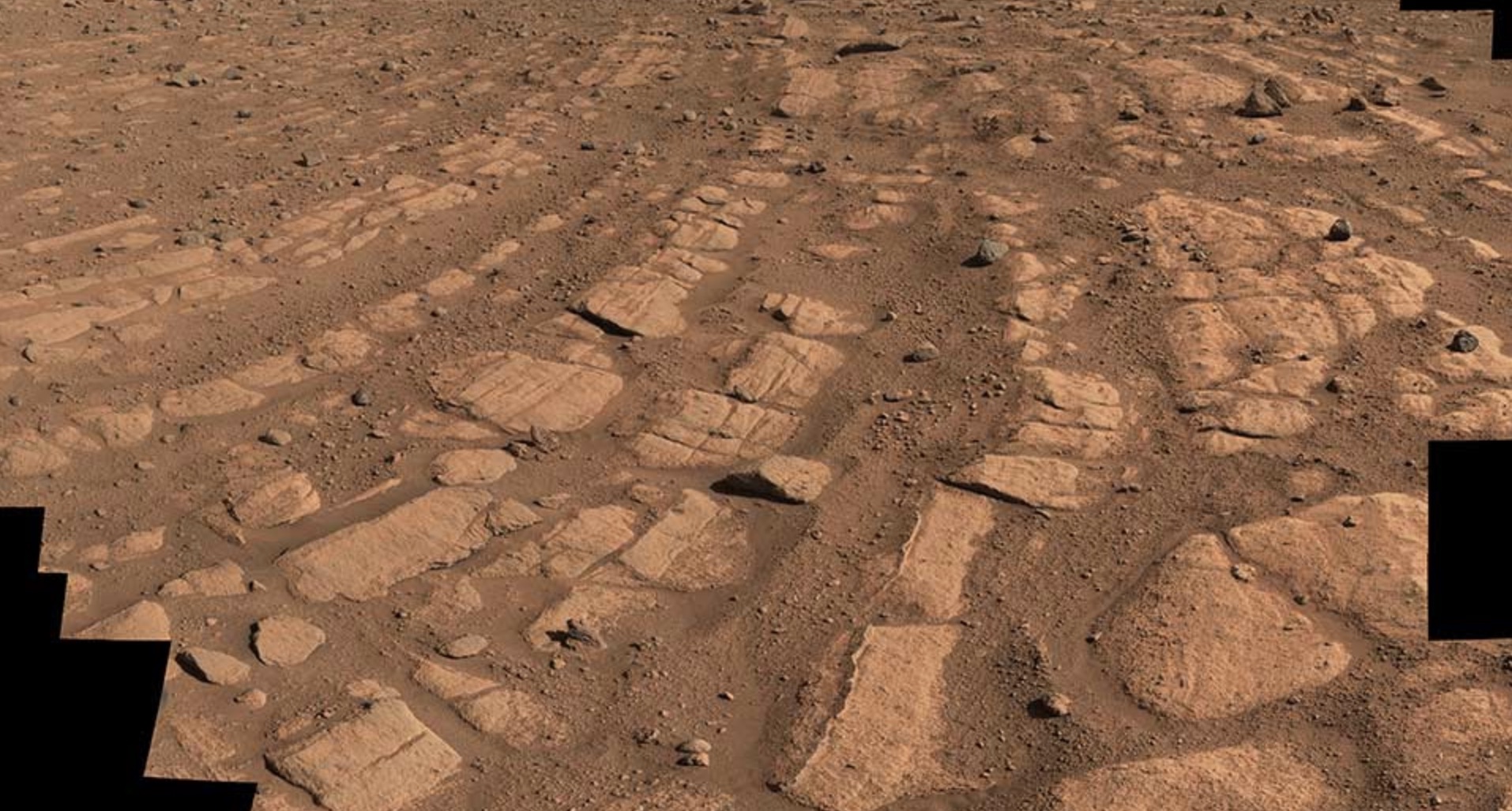

The region where they were discovered has remained geologically inactive and environmentally stable for billions of years. The cold, arid conditions of Mars acted as a natural vault, shielding these delicate molecules from destruction by radiation or erosion.

The data was gathered using SAM (Sample Analysis at Mars)—a compact chemical lab onboard NASA’s Curiosity rover. Since landing in Gale Crater in 2012, Curiosity has used SAM to heat soil samples and analyze their chemical composition using mass spectrometry.

The instrument’s ability to detect longer-chain carbon molecules remotely marks a significant leap for robotic planetary science. Until now, identifying such large organic molecules was thought to be beyond the reach of mobile surface rovers.

How this discovery shapes future missions

This finding comes at a pivotal moment for planetary exploration. Several upcoming missions aim to further explore Mars and other celestial bodies for complex organic chemistry:

-

ExoMars (ESA, 2028): This European rover mission will drill deeper beneath the Martian surface to search for preserved biosignatures.

-

Mars Sample Return (NASA/ESA, 2030s): Designed to bring actual Martian soil samples back to Earth, allowing high-resolution lab analysis of molecules like those just discovered.

-

Dragonfly (NASA, 2034): Headed for Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, this drone will carry an advanced version of SAM to explore Titan’s rich organic environment.

These missions are now better-informed thanks to the organic chemistry insights from Curiosity.

What does this mean for the search for life?

While these molecules alone are not proof of past life, their complexity and preservation point to a chemically rich environment in Mars’s distant past. The fact that they survived for billions of years under Mars’s surface raises new questions:

-

Could similar molecules have formed through biological means?

-

Were conditions on early Mars more favorable to life than previously believed?

This discovery significantly narrows the gap between speculative theories about life on Mars and actual chemical evidence from its surface. As we await new missions to deliver samples or explore other planetary bodies, the presence of such stable organic molecules offers a powerful reminder: Mars still holds many secrets—some possibly tied to the origins of life itself.