Key Takeaways:

- Human habitation in the Pyrenees may have begun earlier than previously thought, with tools dating back 25,000 years found in the Cova dels Tritons.

- Early Homo sapiens adapted to extreme Ice Age conditions in ways that challenge previous theories about human survival and migration.

- The discovery suggests humans shared the caves with predators like leopards and brown bears, complicating our understanding of early human life.

- The find has broad implications for future archaeological studies, opening up new avenues of research into early human resilience in harsh climates.

In a groundbreaking development, archaeologists have uncovered a trove of 25,000-year-old tools in a Pyrenean cave, potentially rewriting the timeline of early human migration into this remote and challenging region. This finding suggests that Homo sapiens may have settled the mountainous Pyrenean valleys thousands of years earlier than once believed, enduring extreme environmental conditions that were previously thought uninhabitable.

The tools, discovered in the Cova dels Tritons, consist of carefully crafted stone blades made from local materials. According to Maite Arilla, a researcher at IPHES-CERCA, these tools bear a striking resemblance to those found in coastal regions. “This new evidence points to a much earlier occupation of the Pyrenees, with technology consistent with the first Homo sapiens in Europe,” Arilla explained.

For years, the extreme cold of the Ice Age was believed to have kept humans away from these valleys until around 20,000 years ago. However, this discovery not only pushes that timeline back but also forces scientists to reconsider how early humans adapted to such harsh conditions.

A Surprising New Chapter in Pyrenean Archaeology

Excavation teams were initially focused on studying the animal life that once thrived in these caves. Previously, the Cova dels Tritons was known primarily as a refuge for predators like leopards and brown bears. Ruth Blasco, another leading archaeologist on the project, expressed her astonishment at the new findings. “We didn’t expect to find evidence of human presence in this cave—until now, it was thought to be used exclusively by carnivores for hunting and hibernation,” she said.

This unexpected discovery adds a new layer to the region’s history, suggesting that early humans found ways to coexist with these predators or perhaps utilized the cave at different times.

Climate and Survival: The Role of Extreme Weather

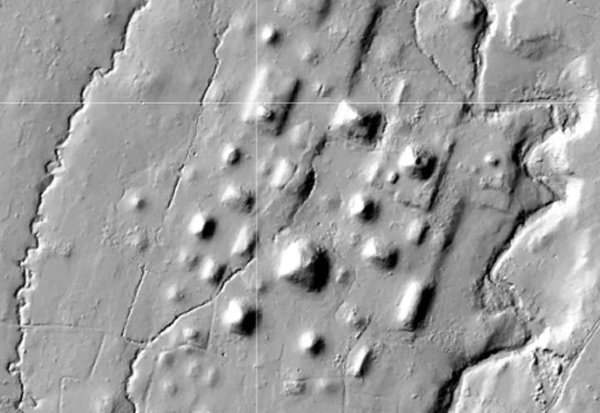

The Pyrenean region, with its dramatic climate fluctuations, presents significant challenges to researchers today, much as it did to early humans. The retreat of glaciers and increasing river erosion make it difficult to study the remnants of past human life. However, the discovery in Cova dels Tritons, along with other findings in nearby caves such as Cova de les Llenes and Cova dels Muricecs, offers a rare glimpse into how these ancient communities survived during one of Earth’s most unforgiving periods.

The Ice Age, marked by drastic shifts in climate, reshaped the landscape and had a profound impact on the survival of species, including Neanderthals, who ultimately disappeared. For Homo sapiens, adaptability to these conditions was crucial. Archaeological evidence, including preserved tools, remains, and environmental samples, has been instrumental in reconstructing these early human strategies for survival.

What’s Next for Pyrenean Archaeology?

This discovery raises critical questions about human resilience and adaptability in the face of extreme climates. As researchers continue to uncover new artifacts in the Pyrenean caves, each finding adds a piece to the puzzle of how early humans lived, hunted, and migrated in Europe during the last Ice Age.

These caves, once thought to have been used only by animals, now offer a deeper understanding of the challenges early humans faced. The artifacts found in the Pyrenees suggest that human ingenuity was not limited by extreme environments but instead thrived in them.

Looking forward, this discovery may lead to a reevaluation of human migration patterns across Europe. It also poses fascinating questions for future archaeological efforts: What other secrets lie buried beneath the caves and valleys of the Pyrenees? How did early humans interact with their environment and the species that shared it? And most intriguingly, how did they survive the Ice Age in regions long considered too hostile for human life?

As research continues, these findings have the potential to reshape our understanding of early human history and provide new insights into the enduring relationship between humans and their environment.