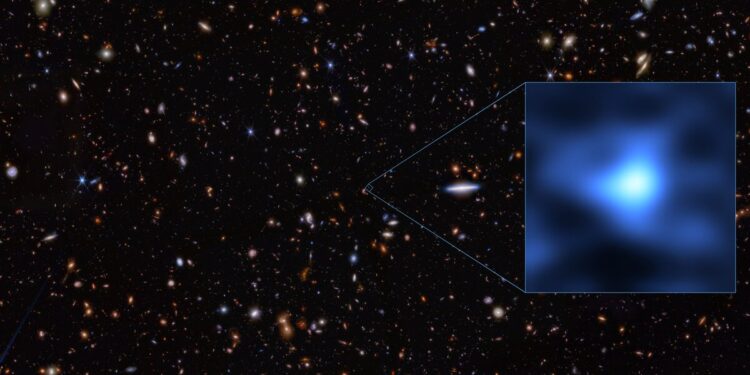

The galaxy, named JADES-GS-z14-0, dates back to a time when the universe was just 294 million years old—barely 2% of its current age. Despite its small size compared to the Milky Way, it’s a cosmic overachiever. Not only is it forming stars at a rapid pace, but it has also been found to contain oxygen, making it the most distant detection of this element to date.

Hydrogen and helium were the only significant elements created during the Big Bang. Heavier elements like oxygen? They come later, forged in the hearts of stars and released into space when those stars die. That’s why finding oxygen in such an early galaxy is surprising—it implies stars had already lived, died, and enriched their surroundings far earlier than anticipated.

“It is like finding an adolescent where you would only expect babies,” said Sander Schouws, a PhD researcher at Leiden Observatory, who led one of the studies.

This discovery paints a dramatically different picture of the early universe. It suggests that galaxy formation wasn’t the slow, gradual process scientists once believed—it was fast, energetic, and chemically active right out of the gate.

What made this discovery possible?

The galaxy was first spotted in 2023 by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), but it was the powerful Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) that revealed its surprising chemical richness. According to the data, JADES-GS-z14-0 contains ten times more heavy elements than scientists expected for a galaxy of its age.

“I was astonished by the unexpected results because they opened a new view on the first phases of galaxy evolution,” said Stefano Carniani from the Scuola Normale Superiore of Pisa, who led the second study.

These findings challenge long-held assumptions and raise new questions. How could such a young galaxy already contain stars old enough to have created oxygen? When did the very first stars form? And could even older, more evolved galaxies be lurking in the cosmic shadows?

A shift in our cosmic timeline

Independent experts are equally intrigued. Gergö Popping, an astronomer at the European ALMA Regional Centre, who was not involved in the research, commented on the groundbreaking results:

“I was really surprised by this clear detection of oxygen in JADES-GS-z14-0. It suggests galaxies can form more rapidly after the Big Bang than had previously been thought.”

The implications go beyond a single galaxy. They touch the very foundation of how we understand the formation of matter, stars, and structure in the universe.

The brightness of JADES-GS-z14-0 makes it an ideal target for future observations. With JWST and ALMA continuing to explore the earliest epochs of the cosmos, scientists are hopeful they’ll uncover even more chemically advanced galaxies in unexpected places. You can read more about the discovery in the studies published in The Astrophysics Journal and Astronomy & Astrophysics.