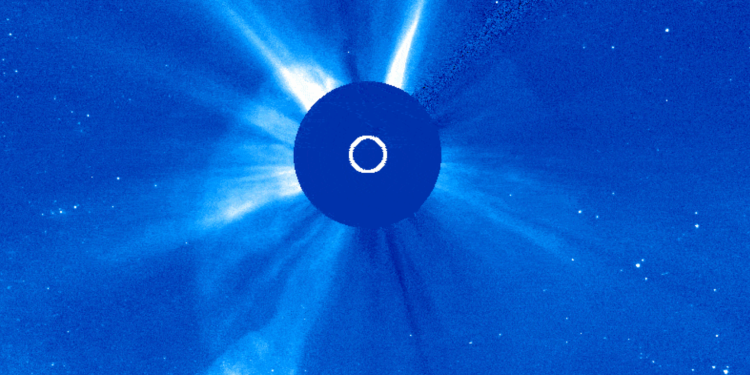

The Sun has once again demonstrated its immense power, as an extraordinarily rare solar event unfolded on December 17. A coronal mass ejection (CME), traveling at more than 3,000 kilometers per second — over 1 percent of the speed of light — erupted from the Sun’s far side. This exceptional phenomenon, which occurs less than once a decade, highlights the dynamic nature of our star and the potential risks it poses to our planet.

Coronal mass ejections are immense bursts of solar plasma and magnetic fields that are ejected into space from the Sun’s corona. While CMEs are not unusual, their intensity and speed can vary dramatically. This recent CME, classified as “extremely rare” due to its extraordinary velocity of 3,161 kilometers per second, stands out as one of the fastest ever recorded. For comparison, most CMEs take several days to reach Earth, but this one would have arrived in just 18 hours if it had been directed toward us.

A Sunspot Stirring Solar Activity

Solar scientists believe this CME is linked to an unusually active sunspot on the far side of the Sun. Sunspots, dark patches caused by intense magnetic activity, are particularly common during the Solar Maximum phase of the solar cycle. Although this specific sunspot has not yet rotated into view, its activity has already been inferred through the series of CMEs observed over the past 10 days. The Sun’s rotation will soon bring this sunspot into view, offering a clearer picture of its dynamics.

The Potential Risks of a Direct Hit

Dr. Ryan French, a solar physicist, explained that if this CME had been Earth-directed, the consequences could have been severe. Such an event would likely trigger a geomagnetic storm capable of disrupting power grids, damaging transformers, and interfering with satellite operations. Beyond technological disruptions, geomagnetic storms also create dazzling auroras visible at much lower latitudes than usual.

The most infamous geomagnetic storm in recorded history, the Carrington Event of 1859, serves as a stark reminder of the risks posed by solar activity. If a similar event occurred today, modern infrastructure would face unprecedented challenges. According to NASA, such a storm could leave tens of millions without power for weeks, disrupting essential services like water supply, communication systems, and transportation. Financial losses from such an event are estimated to range from $0.6 trillion to $2.6 trillion, underscoring the significant stakes involved.

While the December 17 CME was not directed at Earth, it serves as a critical reminder of the importance of monitoring solar activity. Advances in space weather forecasting allow scientists to detect and analyze CMEs in real time, providing valuable insights into their potential impacts. With solar activity expected to peak during the current Solar Maximum, vigilance remains essential to mitigate the risks posed by these extraordinary events.