Andromeda, the closest large galaxy to the Milky Way, has long been thought of as our galactic twin—but new data from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope suggests it’s hiding some major surprises.

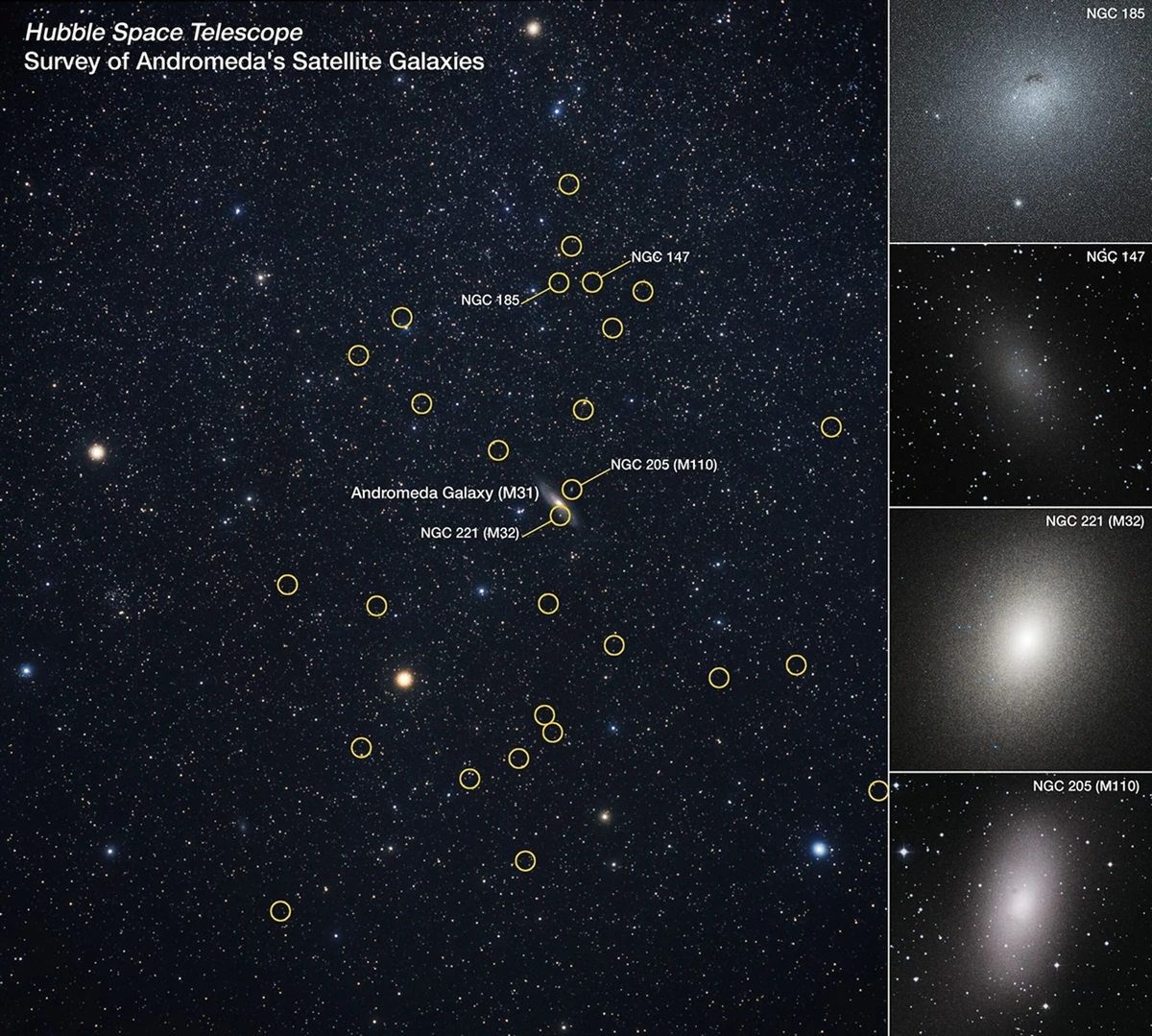

While backyard astronomers see Andromeda as a faint, elongated smudge in the sky, Hubble’s latest observations have revealed a much more bizarre picture. Nearly three dozen small satellite galaxies surround the galaxy, but instead of being scattered randomly, half of them are mysteriously locked into a single plane—moving in the same direction.

“That’s weird. It was actually a total surprise to find the satellites in that configuration and we still don’t fully understand why they appear that way,” said Daniel Weisz of the University of California at Berkeley.

This unexpected discovery, published in The Astrophysical Journal, directly contradicts existing models of galactic evolution. Scientists now believe that something massive and unknown must have shaped Andromeda’s satellite system—but what exactly happened remains a mystery.

Did Andromeda Swallow Another Galaxy?

Astronomers have long suspected that Andromeda had a more violent past than the Milky Way, and these findings add more weight to that theory. Unlike our relatively stable galaxy, Andromeda may have merged with another massive galaxy billions of years ago—an event that could explain its unusual satellite arrangement and larger mass.

“We see that the duration for which the satellites can continue forming new stars really depends on how massive they are and on how close they are to the Andromeda galaxy,” said lead author Alessandro Savino. “It is a clear indication of how small-galaxy growth is disturbed by the influence of a massive galaxy like Andromeda.”

Hubble’s deep survey, which used over 1,000 orbits, also uncovered another major anomaly:

- Some of Andromeda’s dwarf galaxies never stopped forming stars—even when all known models say they should have.

- These galaxies somehow maintained a slow but steady process of star formation for billions of years longer than expected.

“Star formation really continued to much later times, which is not at all what you would expect for these dwarf galaxies,” added Savino. “This doesn’t appear in computer simulations. No one knows what to make of that so far.”

What’s Next? Scientists Are Racing to Find Answers

With so many unexplained patterns surrounding Andromeda, astronomers are now working on a long-term observational campaign to track the exact motions of all 36 of its satellite galaxies.

“Everything scattered in the Andromeda system is very asymmetric and perturbed. It does appear that something significant happened not too long ago,” said Weisz.

In the next five years, Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope will work together to take another set of images, allowing researchers to rewind Andromeda’s history and reconstruct what really happened billions of years ago.

Will this investigation reveal a lost galactic collision? Could Andromeda’s unusual satellite behavior rewrite what we know about galaxy formation? One thing is certain—something strange is happening around Andromeda, and scientists are only just beginning to figure out why.