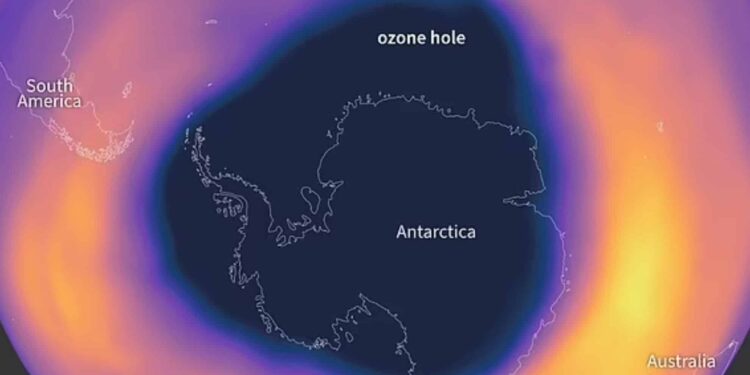

For decades, the hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica symbolized one of humanity’s greatest environmental challenges. New research confirms that our collective efforts to reduce harmful emissions are working, and the ozone layer is on track to fully recover within the next decade.

A study led by researchers at MIT provides the most statistically robust evidence yet that the ozone layer is healing. While previous research suggested a positive trend, this is the first study to confirm, with 95% confidence, that the ozone hole is shrinking due to the reduction of ozone-depleting chemicals.

Susan Solomon, a leading atmospheric scientist and co-author of the study, highlighted the significance of these findings. “For years, we’ve seen qualitative evidence suggesting recovery. This is the first time we’ve been able to quantify it with high certainty,” she explained. “The conclusion is clear: the ozone hole is closing, and it proves that global cooperation can solve environmental crises.”

The Role of the Montreal Protocol

The ozone layer sits between 15 and 30 kilometers (9.3 to 18.6 miles) above the Earth’s surface and acts as a shield, absorbing the Sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation. In the late 20th century, scientists discovered that synthetic chemicals—primarily chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs)—were depleting ozone molecules, creating a massive hole over Antarctica.

These chemicals, once widely used in aerosol sprays, refrigeration, and industrial solvents, released chlorine atoms when exposed to sunlight in the stratosphere. This process accelerated ozone destruction, particularly over Antarctica, where extreme cold and polar stratospheric clouds intensified the effect.

In response, 197 countries and the European Union signed the Montreal Protocol in 1987, banning CFCs and other ozone-depleting substances. This agreement is widely regarded as one of the most successful environmental policies in history.

Why the Antarctic Ozone Hole Was the Most Affected

Antarctica’s unique atmospheric conditions made it particularly vulnerable. During winter, the polar vortex traps ozone-depleting chemicals, and when spring arrives, sunlight triggers reactions that rapidly break down ozone molecules. This is why the ozone hole peaks in size each September as temperatures begin to rise.

Over the last decade, scientists noticed signs of improvement, but natural atmospheric fluctuations made it difficult to determine whether the recovery was a direct result of policy measures or just temporary variability. This new study removes all doubt—ozone levels are rising, and the healing process is progressing as expected.

The Ozone Layer Could Fully Recover by 2035

With 15 years of observational data now available, researchers are confident that the Antarctic ozone hole could disappear completely by 2035 if current trends continue.

“By then, we might witness a year where there’s no depletion at all in the Antarctic. Some of us will live to see the ozone hole gone entirely, and that’s something humanity accomplished together,” Solomon noted.

This milestone not only marks a victory for environmental science but also serves as a powerful reminder that global cooperation can reverse even the most daunting ecological threats.