Astronomers have long suspected that several moons in our Solar System, including those orbiting Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, may conceal vast liquid oceans beneath their frozen crusts. Now, new research suggests that Uranus’s moon Ariel might be offering a rare glimpse into its hidden depths.

Cracks in Ariel’s Surface May Expose Its Interior

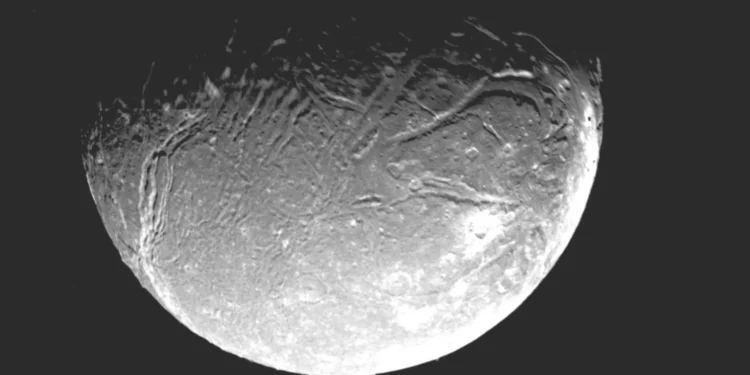

Deep chasms mark Ariel’s surface, and researchers believe these fractures could be transporting material from the moon’s interior to the surface. Among the substances detected is carbon dioxide ice, which suggests the possibility of chemical processes occurring below the crust. If these deposits originated from within Ariel, they may provide a unique window into the moon’s subsurface environment—without the need for complex drilling missions.

“If we’re right, these medial grooves are probably the best candidates for sourcing those carbon oxide deposits and uncovering more details about the moon’s interior,” says planetary geologist Chloe Beddingfield of Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

Unlike other surface features, these chasms appear to be the only structures facilitating material movement from Ariel’s interior, making them particularly valuable for future study.

Earth-Like Geological Processes at Work?

Scientists analyzing Ariel’s terrain have found striking similarities to a geological process observed on Earth known as spreading. This occurs along volcanic ridges where the seafloor slowly separates, allowing molten material to rise and form new crust.

On Ariel, a similar process could be unfolding as warmer material from the moon’s interior forces its way up, splitting the icy surface before filling the cracks. Researchers tested this theory by digitally aligning the two sides of Ariel’s chasms as if “zipping them back up,” and found a perfect match. The presence of parallel grooves along some chasm floors further supports the idea that material has been accumulating over time through repeated geological activity.

Could a Hidden Ocean Be Driving These Changes?

Another factor influencing Ariel’s surface could be gravitational interactions between Uranus and its moons. These interactions, known as orbital resonance, create internal heating that can melt ice and sustain liquid water beneath the crust.

Recent observations from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) provide compelling evidence that a hidden ocean may exist beneath Ariel’s surface. If so, this ocean might be responsible for the carbon dioxide deposits seen within the moon’s deep chasms. However, current data is insufficient to determine the exact size and depth of this possible ocean.

“The size of Ariel’s possible ocean and its depth beneath the surface can only be estimated, but it may be too isolated to interact with spreading centers,” Beddingfield explains.

Despite significant advancements in planetary exploration, much about Ariel remains unknown. While the Voyager 2 spacecraft provided valuable data during its 1986 flyby, it lacked the instruments needed to map the precise distribution of ices on the moon’s surface. Future missions with more advanced sensors will be crucial in determining whether Ariel is truly home to a hidden ocean—and what that might mean for our understanding of ocean worlds beyond Earth.