A groundbreaking study has shed new light on the remarkable expansion of the Clovis culture, North America’s earliest known Paleoindian society. By examining the dietary patterns of a toddler who lived nearly 13,000 years ago in what is now Montana, researchers have revealed that the Clovis people were specialized mammoth hunters. This dietary focus may have been the key to their rapid migration across vast stretches of the continent.

Insights from a Prehistoric Toddler

As revealed by the New York Times, the Clovis culture, renowned for its distinctive tools and projectile weaponry, left behind an extensive archaeological legacy spanning from Canada to Mexico. Despite this widespread impact, human skeletal remains definitively linked to this culture have been scarce. The sole confirmed Clovis individual, a toddler known as Anzick-1, was buried near Wilsall, Montana, around 12,800 years ago. Discovered in 1968 and later reburied in 2014, his remains have provided invaluable insights through genetic and isotopic analysis.

By studying isotopic markers in the boy’s bones, researchers traced his nutrition to his mother, who primarily breastfed him. Astonishingly, nearly 40% of her diet consisted of mammoth meat, supplemented by other large prey like elk, bison, and even an extinct camel species. The almost complete absence of smaller animals and plant matter strongly supports the theory that the Clovis were not general foragers but specialized hunters of megafauna.

James Chatters, one of the study’s authors, explained:

“Because we’re looking at bone protein, which is built up over months, we’re looking at the long-term diet – and what this is telling us is mammoth was a major part of that. It wasn’t just an occasional feast day; it was a normal part of their diet.”

The Key to Clovis Migration

Specializing in mammoth hunting may have given the Clovis people a crucial advantage as they expanded across North America. Ben Potter, another study author, pointed out that their ancestors were already skilled at exploiting mammoths in Eurasia. This expertise allowed them to adapt quickly to their new environment.

“They already knew how to exploit that prey. They’d been doing it for a long time,” said Potter. “So they didn’t have a big learning curve when they moved into a new area.”

Smaller prey species vary greatly by region, requiring localized knowledge and different hunting methods. Mammoths, on the other hand, were consistent in size and behavior across their range, making them an ideal target for a mobile culture.

Mammoths, Climate Change, and Overhunting

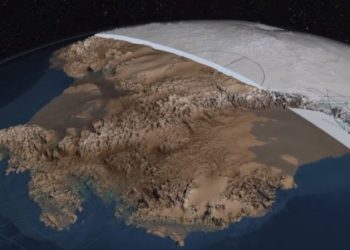

The findings also contribute to the ongoing debate about the extinction of mammoths and other large animals at the end of the Pleistocene epoch, around 10,000 years ago. While climate change likely played a significant role by transforming habitats, human hunting pressure may have compounded these stresses.

“We put back on the table that human hunting pressure could have played a role, particularly in combination with climate change,” Potter explained.

Mammoths were highly mobile animals, migrating across vast distances. Habitat loss due to warming climates could have restricted their movement, making them more vulnerable to skilled hunters like the Clovis people.

Chatters summarized the plight of these ancient giants:

“You’ve got a naive prey under ecological stress. Then you add in these highly capable, very sophisticated, big game hunters, and the outcome is foretold.”

This study, published in Science Advances, highlights the relationship between humans and their environment during a critical period in history, offering profound insights into the challenges faced by both ancient peoples and the megafauna they relied on.