For decades, scientists have searched for a chemical fingerprint that could confirm life exists beyond our planet. But what if one of the most crucial clues has been hiding in plain sight? A groundbreaking study suggests that methane (CH₄), a gas commonly associated with biological activity on Earth, could be the key to detecting extraterrestrial life. Now, a cutting-edge approach could finally make that search more precise than ever.

Why Methane Matters

On Earth, methane is produced by a wide range of biological processes—from microbes deep underground to livestock grazing in fields. While geological activity can also create methane, its presence in a planet’s atmosphere, especially alongside oxygen, could signal active life forms. That’s why a team of NASA-led researchers has developed a powerful new method to analyze this elusive gas in exoplanet atmospheres.

This new method, known as BARBIE (Bayesian Analysis for Remote Biosignature Identification on exoEarths), is designed to cut through the noise and detect methane more accurately than previous methods. Unlike earlier models, which struggled to distinguish methane from other atmospheric elements, BARBIE combines optical and near-infrared (NIR) data to create a clearer picture of a planet’s potential habitability.

A Game-Changer for Space Telescopes

BARBIE’s advanced statistical framework allows astronomers to process massive amounts of observational data quickly. Past studies using similar methods often found that only oxygen-rich atmospheres could be detected in optical wavelengths, leaving too many unanswered questions. By incorporating NIR observations and expanding its parameters, BARBIE could now help reveal the presence of both methane and water vapor—two critical biosignatures.

The implications are massive. NASA’s upcoming Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO), set to launch in the 2040s, will be one of the first missions to directly apply this methodology. Unlike previous exoplanet-hunting missions like Kepler and TESS, which focused on discovering new worlds, HWO’s primary mission will be to analyze the atmospheres of 25 potentially habitable exoplanets. Its powerful instruments will use direct imaging and spectroscopy to search for clear signs of life.

What This Means for the Future of Exoplanet Research

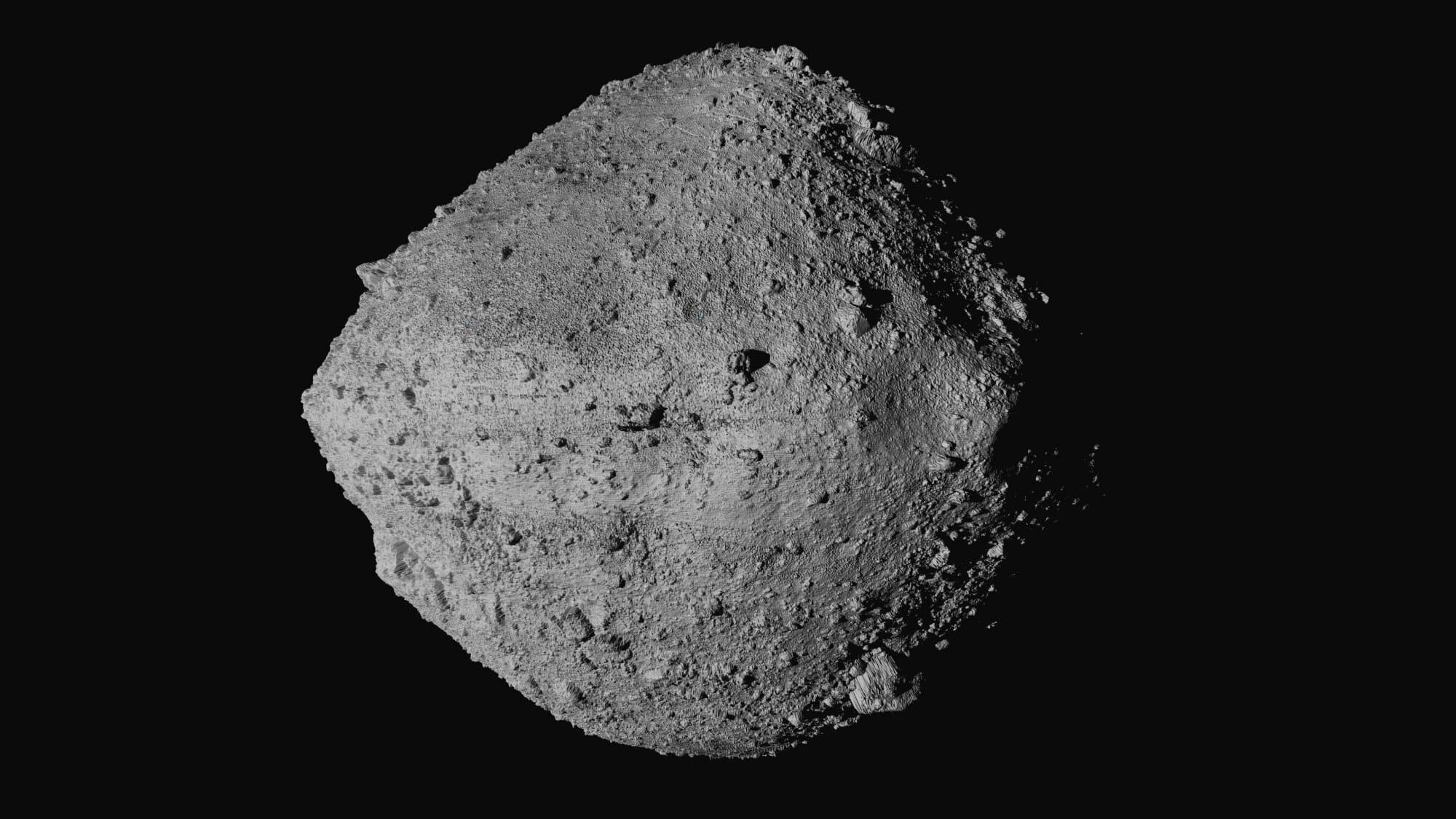

Methane has already raised intriguing possibilities within our own solar system. On Mars, seasonal methane spikes continue to puzzle scientists, while Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, has an entire atmosphere rich in the gas. If methane proves to be a key indicator of biological activity, the search for life on exoplanets could be closer than we ever imagined.

Lead researcher Natasha Latouf from George Mason University explains why this breakthrough is so important in an interview with Universe Today:

“We developed the BARBIE methodology in order to quickly investigate large amounts of parameter space and make informed decisions about the resultant observational trade-offs. Methane is a key contextual biosignature that we would be very interested in detecting, especially with other biosignatures like O2.”

With over 5,800 confirmed exoplanets and more than 200 classified as rocky, Earth-like worlds, the search for alien life is moving faster than ever. The TRAPPIST-1 system, just 40 light-years away, contains several Earth-sized planets in the habitable zone, making it one of the most exciting targets for future missions. Even closer to home, Proxima Centauri b, the nearest known exoplanet, remains a compelling candidate for follow-up studies—though intense radiation from its star poses challenges for habitability.

Could We Find Life in Our Lifetime?

While the search continues, Latouf remains optimistic:

“In my opinion, I think that we will,” Latouf says. “Will that happen in my lifetime? That I’m not sure of—but I do believe we’re going to find life eventually! Although it’ll sound boring the most Earth-like planet I’m interested in is…Earth. We have this wonderful gift in this planet, with all the exact right conditions. We need to be making sure we’re preserving it and understanding our own planet before we dive into the search for others!”

For now, Earth remains the only known planet capable of supporting life. But with new technology, innovative research methods, and missions like HWO on the horizon, the answer to one of humanity’s biggest questions could finally be within reach.