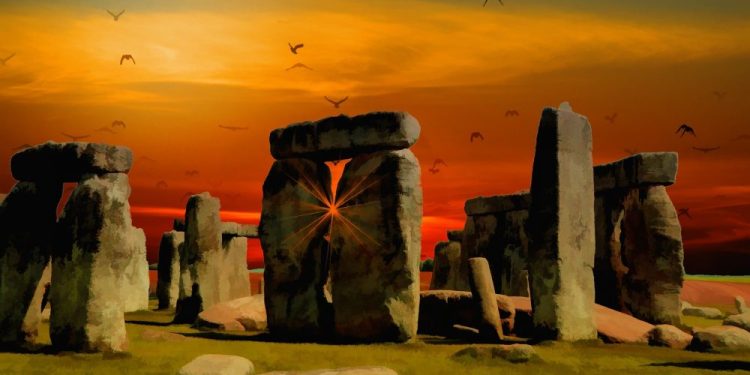

For centuries, Stonehenge has stood as an iconic symbol of prehistoric engineering, shrouded in mystery and speculation. But what if it wasn’t the first of its kind? A recent breakthrough suggests that another stone circle—Flagstones in Dorset—predates Stonehenge by centuries, potentially reshaping what we know about ancient Britain’s ceremonial sites.

A Forgotten Monument Hidden Beneath a Road

Located roughly 78 kilometers (48 miles) southwest of Stonehenge, Flagstones has not been discovered recently. It was first unearthed in the 1980s during construction of a bypass. Despite its significance, development continued, leaving half of the ancient site buried beneath modern infrastructure.

Yet, the portions that remain accessible have provided a wealth of information. Archaeologists have long debated Flagstones’ true purpose and age, comparing its features to other Neolithic and Bronze Age structures.

Dr. Susan Greaney, an expert in ancient British monuments at the University of Exeter, explained:

“Flagstones is an unusual monument. In some respects, it looks like monuments that come earlier, which we call causewayed enclosures, and in others, it looks a bit like things that come later that we call henges.”

Flagstones Predates Stonehenge

Originally, researchers estimated that Flagstones was built around 2900 BCE—the same era as Stonehenge’s earliest phase. Its circular layout, construction using antler picks, and even the burial practices bore striking similarities to the world-famous site.

However, thanks to advances in radiocarbon dating, scientists from ETH Zürich and the University of Groningen conducted a far more precise analysis. The results were astonishing: Flagstones wasn’t built in 2900 BCE but as early as 3650 BCE, with additional features added around 3200 BCE.

This means Flagstones predates Stonehenge by at least 500 years.

Could Flagstones Have inspired Stonehenge?

The implications of this discovery are profound. If Flagstones existed long before Stonehenge, was it a prototype that influenced its more famous counterpart? Or does this mean archaeologists need to rethink the timeline of Stonehenge itself?

According to Dr. Greaney, this finding significantly alters our understanding of prehistoric Britain:

“The chronology of Flagstones is essential for understanding the changing sequence of ceremonial and funeral monuments in Britain. Could Stonehenge have been a copy of Flagstones? Or do these findings suggest our current dating of Stonehenge might need revision?”

This discovery doesn’t just impact how we view Stonehenge—it reshapes the broader narrative of prehistoric Britain. If Flagstones played a role in influencing later sites, it could indicate a longer, more complex tradition of monument-building than previously thought.

Further excavations and studies may reveal even older sites, challenging our perceptions of ancient societies and their architectural ambitions. One thing is certain: history is still being written, and new revelations could change everything we thought we knew about Britain’s past.