For years, astronomers have been captivated by a fundamental question: is the Milky Way galaxy a rare gem in the universe, or is it more ordinary than we think? This journey to uncover the true nature of our galactic home began over a decade ago with the launch of the Satellites Around Galactic Analogs (SAGA) Survey in 2013. The project aimed to study systems of galaxies that mirror the Milky Way, helping us determine whether our galaxy holds a special place in the universe.

Recently, three pivotal research papers emerged from this initiative, offering fresh perspectives on the Milky Way’s uniqueness. These findings were made publicly available on the arXiv preprint server, following the completion of a comprehensive census of 101 satellite systems similar to our own. What they found could change the way we understand our galaxy’s role within the cosmic web.

What Are Satellite Galaxies?

Just like moons orbit planets, smaller galaxies—called satellites—orbit larger ones, known as host galaxies. These satellite galaxies are gravitationally bound to their hosts, influenced by the massive presence of both the central galaxy and its surrounding dark matter.

In our Milky Way, some of the most famous satellite galaxies are the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) and Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC), both of which can be seen with the naked eye from the Southern Hemisphere. However, many more faint satellite galaxies exist, orbiting unseen except through powerful telescopes.

The SAGA Survey’s mission was clear: study these satellite systems around galaxies that have stellar masses comparable to the Milky Way. Led by Yao-Yuan Mao from the University of Utah, along with collaborators Marla Geha (Yale University) and Risa Wechsler (Stanford University), the team aimed to uncover whether the Milky Way’s satellite system was unique or typical of galaxies of its size.

The Milky Way Might Be an Outlier

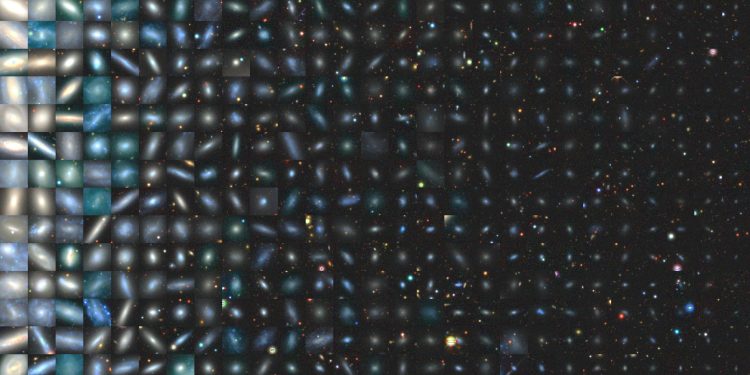

In the first study, Mao’s team revealed some intriguing results. After studying 378 satellite galaxies across 101 Milky Way-like systems, they found that the number of confirmed satellites per system varied significantly, ranging from zero to 13. The Milky Way, with four confirmed satellite galaxies, falls comfortably within this range—yet there’s a twist. According to Mao, the presence of the Large Magellanic Cloud complicates the picture.

Their research indicated that systems hosting a massive satellite, such as the LMC, generally have more satellites overall. This makes the Milky Way somewhat of an outlier, as it has fewer satellites than expected for a galaxy with such a large companion.

One reason for this discrepancy could be timing. The Milky Way acquired the LMC and SMC relatively recently in cosmic terms, meaning it hasn’t had as much time to collect additional satellites compared to other systems. This discovery highlights the complex interactions between host galaxies and their satellites, offering a fresh lens through which to view the Milky Way.

Why Do Some Galaxies Stop Making Stars?

The second study, led by Geha, delves into an equally fascinating question: what causes satellite galaxies to stop forming stars? Known as “quenching”, this phenomenon is critical to understanding galaxy evolution. Geha’s team found that satellites closer to their host galaxies were more likely to have their star formation quenched. This suggests that the environment surrounding a galaxy plays a significant role in determining whether it continues to birth new stars or falls dormant.

The third study, led by Yunchong (Richie) Wang, takes the SAGA data and applies it to improve models of galaxy formation. Their research predicts that quenched galaxies should also exist in more isolated areas of space, a theory that future astronomical surveys may be able to test. This is a significant leap forward in our understanding of how galaxies evolve over time, especially in relation to their environments.

A Treasure Trove for Astronomers

Beyond these groundbreaking discoveries, the SAGA team has gifted the broader astronomical community with a wealth of data. As part of their study, they have published redshift measurements—critical data for determining the distance of objects in space—for about 46,000 galaxies. This treasure trove will allow researchers to explore a range of questions beyond satellite galaxies, making it a valuable resource for years to come.

As Mao puts it, “Finding these satellite galaxies is like finding needles in a haystack. We had to measure the redshifts of hundreds of galaxies just to identify one satellite.” Thanks to their perseverance, the cosmic haystack has yielded precious insights that could reshape our understanding of galaxy formation and evolution.

With these revelations in hand, the Milky Way might not be as special as we once thought—or it could be a rare case in a universe filled with diversity. Either way, the SAGA Survey has opened up exciting new avenues for exploration, and future studies will continue to refine our picture of the galaxy we call home.