Recent genetic studies of ivory artifacts unearthed across Europe provide compelling evidence that Norse hunters ventured into North American waters and interacted with Indigenous peoples over 500 years before Columbus’ arrival in the Americas. The findings, which focus on the analysis of walrus tusks, indicate that these early explorers were active in North Atlantic waters, particularly around present-day Canada, as far back as 985 CE.

Tracing the Origins of Ancient Walrus Ivory

Researchers conducting isotopic and genetic analysis of the ivory artifacts identified the source of the tusks as walruses inhabiting the waters near modern-day Greenland and Canada. This discovery sheds new light on the extent of the Norse trade networks, suggesting that these early hunters faced arduous journeys and challenging climates, possibly leading to contact and trade with Indigenous communities.

Walrus ivory was highly valued in medieval Europe, where it was traded extensively, with Norse traders playing a crucial intermediary role. However, until now, the exact origins of this ivory remained a mystery. The study’s findings raise intriguing questions about the sustainability of walrus hunting and whether the Norse maintained direct contact with Indigenous Arctic populations or relied on other forms of trade.

The Greenland Norse and the Expansion of Hunting Grounds

As demand for ivory surged in medieval Europe, Norse settlers established themselves in southwestern Greenland as early as 985 CE. Armed with advanced maritime technology for the time, these “Greenland Norse” expanded their hunting territories, targeting fertile walrus populations.

Though evidence of Norse settlements in North America, such as the famed L’Anse aux Meadows site, exists, this research marks the first genetic link that suggests interactions between Norse explorers and Indigenous North Americans. Until now, there was no solid proof of trade or contact between these groups during this early period.

The Study: A New Look at Norse-Indigenous Interactions

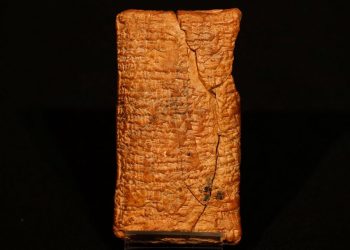

Leading the research, a team of scientists from the University of Copenhagen, led by Emily Johana Ruiz Puerta, analyzed ivory artifacts dated between 850 and 1350 CE. Their goal was to trace the origins of walrus tusks that reached Europe via Greenland. The researchers utilized advanced genomic sourcing methods, comparing the DNA from these ancient tusks to modern walrus populations.

This analysis revealed distinct patterns, showing that the Greenland Norse methodically expanded their hunting range, eventually depleting local walrus populations and pushing their activities further into North American waters. By 1120 CE, the study found that over half of the ivory tested came from the northern waters of the Davis Strait, a vast hunting ground shared with Indigenous groups.

Did Norse Hunters Trade with Indigenous Peoples?

While the study concludes that large-scale trade between the Norse and Indigenous groups may have been unlikely before 1120 CE, it opens the door to the possibility that the two groups interacted. The evidence points to overlapping hunting territories, suggesting that encounters may have occurred, particularly as the Norse expanded their range.

The Greenland Norse likely knew of the Inuit and Tuniit peoples, and the initial encounters may have prompted exploration into formalized trade. However, what the Norse might have offered in exchange for ivory remains unclear. The researchers also tested the limitations of Norse seafaring technology, noting that their ships were likely constrained by both time and cargo capacity, making long-range hunts increasingly impractical.

A Narrow Window for Exploration

With the harsh Arctic environment and limited ice-free seasons, the Greenland Norse faced significant challenges during their long-range expeditions. The study found that the hunters had as little as two weeks to collect ivory before being forced to return. This limited time, combined with the small size of their communities and restricted cargo space, may have led the Norse to consider trading with Indigenous groups as an alternative to direct hunting.

Although the study offers compelling genetic evidence, the researchers emphasize that more archaeological findings are necessary to confirm direct interactions between the Norse and Indigenous North Americans. However, the expanding range of walrus hunting suggested by the data makes it increasingly likely that such contact did occur centuries before Columbus’ arrival.

The study concludes by suggesting that these interactions if confirmed, could represent one of the earliest examples of “circumpolar globalization,” as groups from across the Atlantic Ocean reconnected after tens of thousands of years of separation.