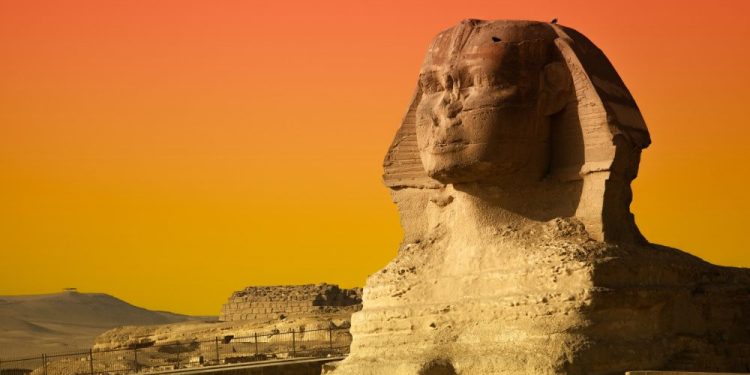

The Great Pyramids of Giza stand as one of humanity’s most ambitious engineering feats, but just a short distance away, the Great Sphinx holds an even deeper mystery. Unlike the carefully placed limestone blocks of the pyramids, this colossal lion-bodied statue with a human face may not have been entirely sculpted by human hands. Instead, some experts suggest that natural forces could have played a key role in shaping its form long before ancient Egyptian artisans refined its appearance.

A Theory That Challenges Traditional Views

For decades, scholars have debated whether the Great Sphinx was carved entirely from a solid rock formation or whether nature itself provided the initial shape. In 1981, geologist Farouk El-Baz proposed that the ancient Egyptians may have worked with pre-existing formations shaped by desert winds rather than sculpting the monument from an unaltered block of limestone. His idea gained little traction at the time, but recent scientific experiments suggest he might have been onto something.

A team of researchers from New York University, led by physicist Leif Ristroph, conducted a fascinating experiment in 2023 to test this hypothesis. Their study, published in Physical Review Fluids, used fluid dynamics to simulate how natural erosion could lead to sphinx-like formations in the landscape.

To explore the effects of erosion, the researchers crafted miniature lion-like structures using bentonite clay—a material that erodes in water similarly to how wind wears down desert rock. They placed a harder, non-erodible plastic object at the front of the clay mounds to represent areas of more resistant rock. When water flowed over these formations, something remarkable happened: the surrounding clay eroded away while the harder material remained, forming a shape strikingly similar to a sphinx.

As Ristroph explained, the fluid not only removed softer material but also adjusted its course around the resistant sections, further refining the shape. This process closely resembles how wind sculpts geological features in arid regions, such as yardangs—sharp, wind-carved ridges found in many deserts, including Egypt’s Western Desert.

Could the Sphinx Have Started as a Naturally Shaped Yardang?

The findings support the idea that the Great Sphinx may have originated as a naturally occurring yardang, which was later refined by ancient stonemasons into the legendary guardian we see today. The researchers even introduced dye into their water experiments, revealing how wind patterns might have accentuated features like the neck and paws by accelerating erosion in certain areas.

If true, this would mean that the Egyptians did not build the Sphinx entirely from scratch but rather enhanced an existing natural formation, a process that would have significantly reduced the effort required to carve such a massive structure.

While this theory does not disprove the traditional belief that the Sphinx was carved directly from limestone, it adds a new layer to its already enigmatic history. Whether shaped by wind before human hands refined its features or entirely sculpted by ancient builders, the Great Sphinx remains one of the world’s most iconic monuments, continuing to captivate millions of visitors each year.