Around the world, ancient myths describe devastating events—floods, fire from the sky, days of darkness, and the collapse of entire civilizations. These stories have often been treated as fiction or metaphor. But what if they preserve clues about a forgotten cycle of global cataclysms?

Instead of isolated folklore, many of these myths may represent fragmented memories of real events that occurred long before modern history began. And instead of being random, those events may have followed patterns. Some researchers now argue that we are missing an ancient understanding of how destruction comes not just once, but again and again.

Ancient stories that echo the same warning

Cultures that never interacted still left behind remarkably similar tales. Flood myths exist on every continent. The Epic of Gilgamesh in Mesopotamia, the story of Noah in the Middle East, the legend of Manu in India, and the flood narratives among the Hopi, Maori, and Yoruba people all describe overwhelming deluges that erased earlier worlds.

These are not tales of heavy rain or local disasters. They describe oceans rising over mountains, entire lands disappearing, and only a handful of survivors rebuilding what was lost.

Many traditions also speak of fire from the sky. Norse mythology ends in flames. Zoroastrian teachings include a world-cleansing fire. The Aztecs believed one of their previous suns ended in flames. Some Aboriginal Australian stories describe stars falling and setting the land alight.

Darkness is another common thread. Egyptian texts mention days without sunlight. Hindu scriptures speak of an age of darkness, Kali Yuga. The Bible refers to the sun being darkened. In Mesoamerican myth, some world ages ended in a darkened sky and the absence of light.

These themes—water, fire, and darkness—are found across ancient myth, separated by geography and language. The repetition suggests more than coincidence. It hints at cultural memory of a forgotten cycle of global cataclysms.

Not linear, but cyclical time

Ancient civilizations did not always see time the way modern cultures do. Today we think in terms of progress and linear development. But in many ancient traditions, time moves in great cycles, each ending in destruction before renewal.

In Hindu cosmology, the Yuga cycle describes four ages. Each age sees a decline in morality and order, ending with devastation before the return of the golden age. According to some interpretations, we are nearing the end of Kali Yuga, the darkest phase.

The Aztecs described five previous suns, each representing a world age. Four have ended in catastrophe. The fifth, our current age, is believed to end with earthquakes.

Plato described a lost civilization—Atlantis—that fell in a single night of floods and earthquakes. He claimed this was not unique but part of recurring global resets known to Egyptian priests. He spoke of time as containing repeated “cataclysms” that wiped clean the memory of humanity.

These ideas all reflect an awareness of a forgotten cycle of global cataclysms. Civilizations were seen not as permanent, but as vulnerable to periodic collapse.

Earth’s long rhythms and forgotten science

Some researchers believe these myths preserve real events—possibly triggered by natural cycles we’ve only recently begun to understand.

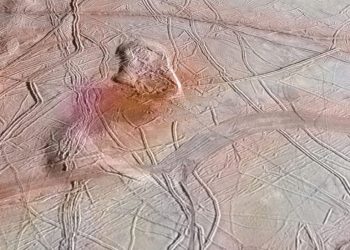

One of these is Earth’s axial precession, a 26,000-year wobble that shifts the position of stars in the sky over time. Some ancient sites, like the Sphinx and Stonehenge, appear to align with stars in ways that match not the present sky, but the sky of ancient epochs. This has led to speculation that ancient cultures were tracking time on cosmic scales.

Another candidate is cosmic impact. The Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis suggests that around 12,800 years ago, a fragmented comet struck Earth, causing sudden cooling, mass extinctions, and enormous fires across North America. This timing aligns closely with many flood myths and with the end of advanced prehistoric cultures like the Clovis.

Even solar activity might play a role. Some traditions describe the sun behaving strangely—growing dark, changing color, or acting violently. These could be ancient observations of solar flares, magnetic disruptions, or atmospheric changes following comet impacts.

While mainstream science debates these theories, the ancient stories do not shy away from describing worldwide destruction. The key question is whether they are describing fiction—or a pattern we have forgotten.

Myth as encoded memory

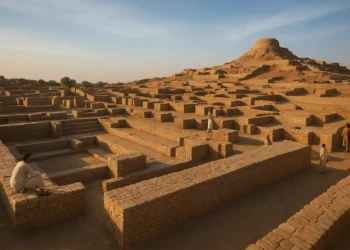

Writers like Graham Hancock, Randall Carlson, and others have popularized the idea that myths are not superstition, but information preserved through symbolism and story. They argue that ancient structures, oral traditions, and ritual calendars were part of a global system meant to remember past cataclysms. One example according to some authors is Göbekli Tepe.

Many ancient monuments are aligned with stars, solstices, or equinoxes. Some appear to be maps of the sky or calendars tracking long cycles. Petroglyphs and sacred texts often describe disasters in symbolic terms—dragons, floods, heavenly fire—that may represent real events experienced by ancient people.

While these theories are controversial, they force us to ask difficult questions. Why do myths around the world describe similar events? Why do so many refer to a world before the current one? And why were ancient people so focused on preserving this knowledge?

Perhaps they were trying to pass on more than culture. Perhaps they were trying to warn us.

A message for the present age

Modern life feels stable—until it doesn’t. Earthquakes, volcanoes, solar flares, asteroid near-misses, and rapid climate shifts all remind us how fragile civilization really is.

The ancient world may have known this better than we do. Their stories speak not only of disaster but of recovery. The survivors of the last cycle built again. They told their children. They carved the warnings into stone.

Maybe myths are more than imagination. Maybe they are fragments of a survival manual.

The forgotten cycle of global cataclysms might not be a relic of the past. It might be a reality we are part of, one we no longer see because we stopped looking. The ancient world remembered. The question is whether we are still capable of doing the same.