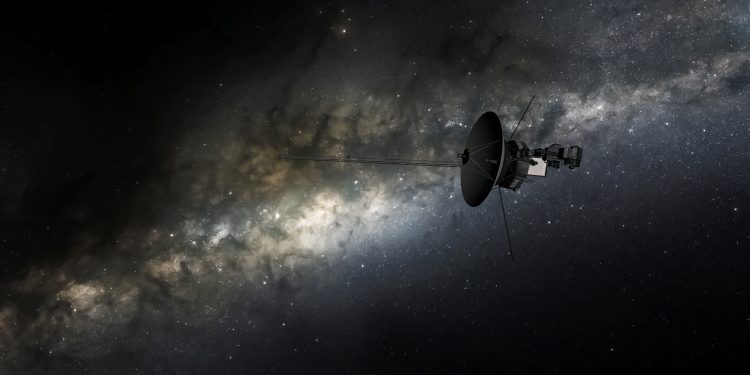

In a fascinating achievement, a group of amateur astronomers in the Netherlands has successfully captured a faint signal from NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft, currently located an astonishing 24.9 billion kilometers (15.5 billion miles) away from Earth. Using the Dwingeloo radio telescope, a facility now preserved as a national monument, the astronomers proved that even non-professional enthusiasts can contribute to exploring the cosmos.

Launched in 1977 alongside its twin, Voyager 2, Voyager 1 has been traversing the outer reaches of our Solar System for nearly five decades. During its journey, the spacecraft has delivered groundbreaking data about Jupiter, Saturn, and interstellar space. However, its age and limited resources have begun to take a toll. To extend its operational life, NASA has deactivated several scientific instruments and dealt with technical glitches, including a six-month period last year when the spacecraft sent unintelligible data back to Earth.

Most recently, on October 19, communication with Voyager 1 was lost entirely. In a surprising turn of events, the spacecraft’s onboard systems autonomously resolved the issue by switching to an alternative transmitter, the S-band, which had not been used since 1981. NASA’s engineers were initially unsure whether this weaker transmitter could overcome the vast distance, but the Deep Space Network (DSN) successfully detected the signal.

Amateur Astronomers Step Up

What makes this recent detection extraordinary is that it wasn’t carried out by NASA’s powerful DSN alone. Amateur astronomers, using the much smaller Dwingeloo radio telescope, also managed to pick up Voyager 1’s faint signal. This feat required overcoming significant technical challenges. According to the C.A. Muller Radio Astronomy Station (CAMRAS), the telescope’s dish is not optimized for the higher frequencies used by Voyager 1. To compensate, the team added a new antenna and used orbital predictions to account for the Doppler shift caused by the relative motion of Earth and the spacecraft.

“By correcting for the Doppler shift, we were able to see the signal live in the observation room,” CAMRAS shared in a blog post. “Subsequent analysis confirmed that the frequency shift matched Voyager 1’s orbital trajectory.”

At four times the distance of Pluto, Voyager 1’s signal took over 23 hours to reach Earth. This accomplishment places the Dwingeloo telescope among a select few instruments capable of receiving data from the spacecraft.

Meanwhile, NASA continues efforts to restore Voyager 1 to optimal functionality. Engineers have successfully reactivated the primary X-band transmitter, and the spacecraft has resumed data collection using its four remaining operational scientific instruments. Despite its advanced age and dwindling power reserves, Voyager 1 may still have a few years left to provide invaluable insights into the universe beyond our Solar System.