Long before written language or organized religion, early humans were already crafting symbols of identity, ancestry, and the unknown. Among the most enigmatic artifacts from this period are a small group of objects few have ever seen: ancient stone masks carved over 9,000 years ago.

In a remote part of the southern West Bank near Pnei Hever, one such mask was unearthed — a rare and haunting relic of a culture just beginning to settle into agricultural life.

The design of devotion

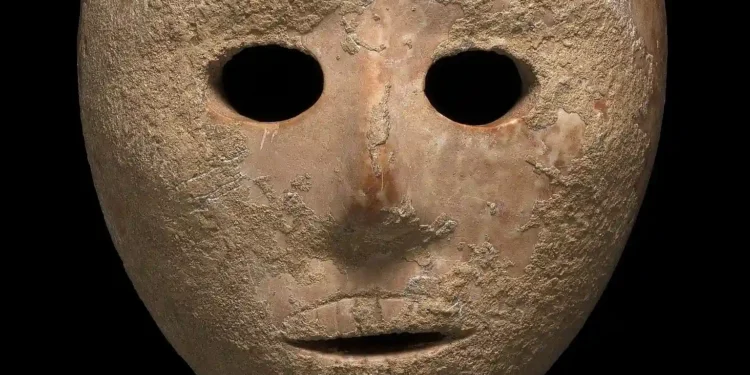

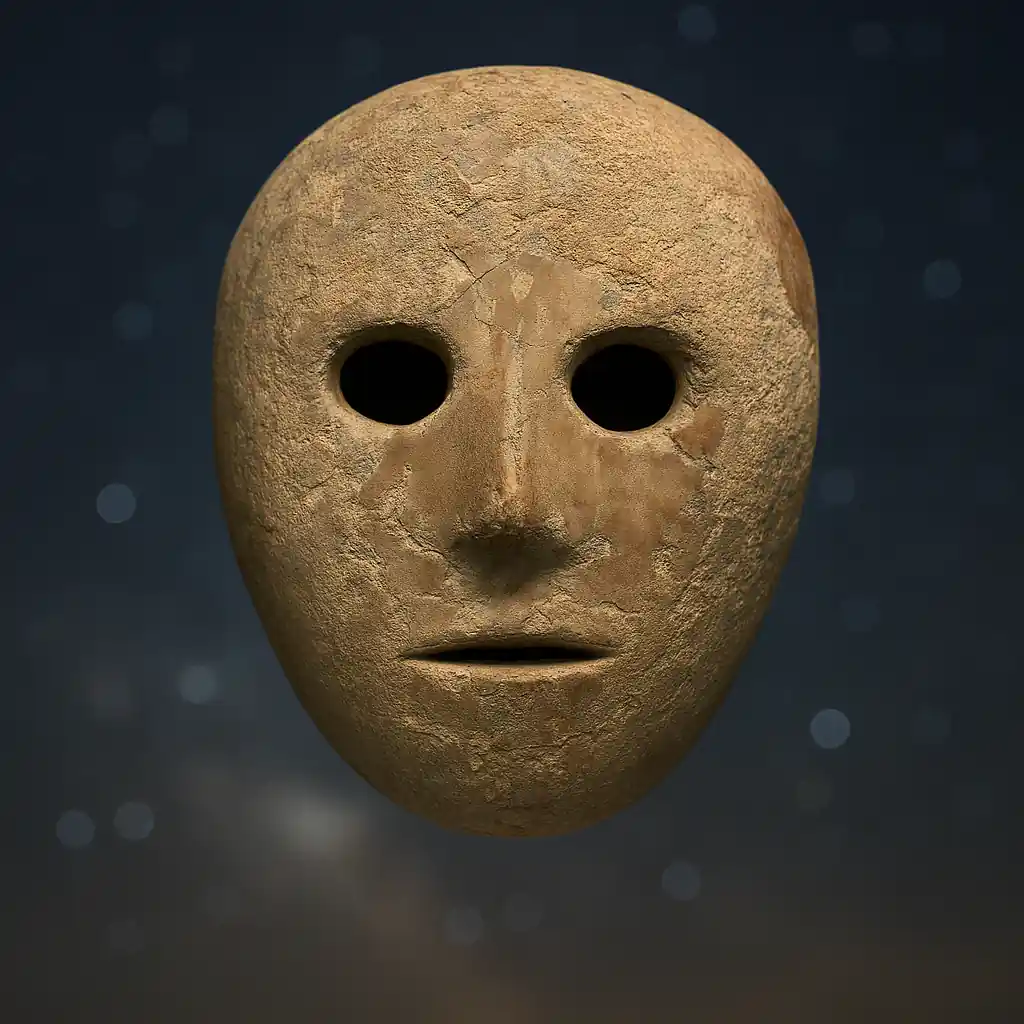

Carved from limestone and polished to near perfection, the mask is life-sized, with deep eye sockets, a pronounced nose, and subtle cheekbones. Four small holes around its edges suggest it was meant to be worn — or perhaps displayed — during rituals. Its surface, now weathered, was likely painted in vivid colors, long since lost to time.

What sets this ancient stone mask apart is not just its craftsmanship, but its rarity. It is one of only 15 ancient stone masks ever discovered — and one of the few whose origin and context are clearly known.

Ronit Lupu of the Israel Antiquities Authority described the find as extraordinary:

“The stone has been completely smoothed over, and the features are perfect and symmetrical, even delineating cheekbones. Discovering a mask made of stone at such a high level of finish is very exciting.”

A glimpse into Neolithic ritual

This ancient stone mask dates to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period, a time of monumental change in human society. As communities began domesticating plants and animals, the shift from hunter-gatherer life to settled farming was not only economic — it was spiritual.

According to Omry Barzilai, head of the IAA Archaeological Research Department, these masks are closely tied to the emergence of organized ritual:

“Stone masks are linked to the agricultural revolution… accompanied by a change in social structure and a sharp increase in ritual-religious activities.”

Alongside plastered skulls and human figurines, these ancient stone masks appear to have been used in ancestor worship — ceremonies designed to connect the living with the dead, maintain family heritage, and perhaps invoke protection or fertility.

Many of the skulls from this era were buried beneath homes, deliberately shaped or decorated — a symbolic reminder of the enduring presence of one’s lineage. Masks like the one from Pnei Hever may have played a similar role.

A legacy carved in stone

Far from being simple artifacts, these masks reflect the beliefs and emotions of a society just beginning to shape its connection to the dead — and to the divine.

With only 15 known to exist worldwide, their scarcity makes them even more remarkable. Most were found without clear archaeological context, passed down through private collections, or discovered by chance. Only a few, like the one unearthed near Pnei Hever, come with verified provenance, allowing scientists to link them to a specific time, place, and cultural shift.

Their faces — stylized but unmistakably human — may represent the dead, the divine, or something in between. They were likely used in rituals that helped people connect with ancestors or mark seasonal transitions in a world newly shaped by agriculture and permanence.

What they offer isn’t just insight into early art, but into the birth of symbolism, memory, and belief itself. Through these stone faces, we glimpse the dawn of a human consciousness that was beginning to ask bigger questions — and carve the answers into stone.