Have you ever wondered why Niccolo Machiavelli has been amongst the most analyzed and talked about philosophers in the entire history of humanity? We will provide you with our version of the answer. It’s pretty simple.

Niccolo Machiavelli has made some of the most controversial, atrocious, and ferocious comments and theories in the world, making common sense and showing the world’s reality as a whole. He was never afraid to speak his mind, and he never accepted the approach of sugarcoating the truth.

Who is Niccolo Machiavelli?

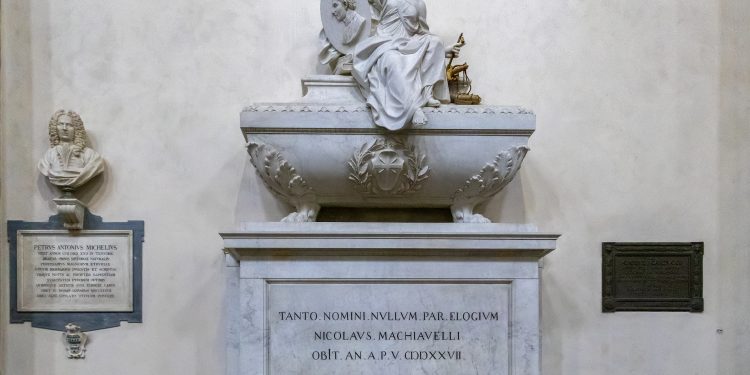

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli was born in May of 1469 and died around June 1527. He was an Italian author, historian, and diplomat, while the most important of his work was being a philosopher. He was blessed enough to have been part of the Renaissance, and we are fortunate enough to possess his work concerning the political societies of that time.

Enough of the generalities. He is best known for his political treatise The Prince (Il Principe), published in 1532. In this particular work, he focuses his analysis on three major topics of political life. Firstly, how one should get power in politics and how he could maintain it. Secondly, whether a ruler should be able to control luck and fate and how it affects his reputation. Finally, how are deception and lying the best way for a ruler to gain popularity, not based on his political action but on his conception and appearance as a political ruler?

Today, we are analyzing his work as far as the war and force in a political community are concerned. The following points will be concise and clear, aiming at helping you understand his controversial and, at times, misunderstood position on the well-being of a political community.

Machiavelli on War & Command

1. “There is no avoiding war, it can only be postponed to the advantage of your enemy.”

If you think that as a ruler, you will always keep your hands clean and never have to use your army to fight your enemy, you are highly mistaken, and frankly, for Machiavelli, you have chosen the wrong path to follow.

Politics is the world of war. Avoiding war will only give an advantage to your enemy. Why? Because the opposing side might have already understood the business of politics and, most importantly, the next point of the analysis.

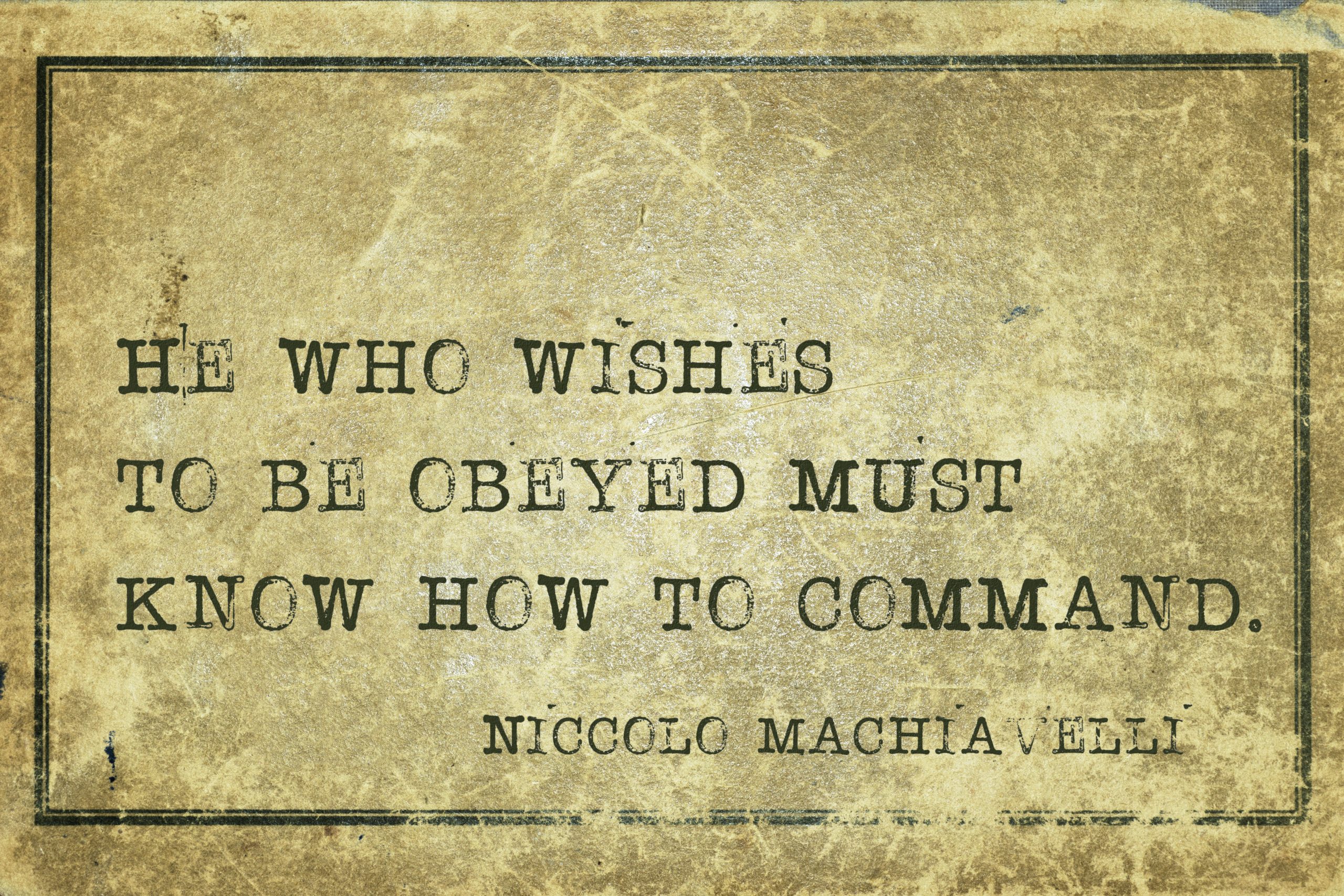

2. “He who wishes to be obeyed must know how to command.”

Why? Because people fearing you is better than people loving you. And why’s that? Because you always need a small portion of the people to be with you or you have to control the army, even a small portion of it. Hence, you always have the resources to command the people if something goes wrong.

For Machiavelli, politics is strongly connected to commanding. People won’t always listen to someone who only asks to be obeyed. People will have to be hesitant to act unjustly or wrongfully because they have someone who can command as the ruler.

Fundamental Political Problem

3. “There is simply no comparison between an armed man and one who is not. It is simply unreasonable to expect that an armed man should obey one who is unarmed, or that an unarmed man should remain safe and secure when his servants are armed.”

With this quote, Machiavelli can just sum up the reality in politics since the beginning of the time that such an institution existed. Why are so many governments failing? Because there’s no balance between the man who is unarmed and thinks that the armed man will obey his order and the man who is armed and believes that the unarmed man feels safe.

In reality, the unarmed man isn’t taking action because he is afraid for his life, and the armed man will never obey someone who doesn’t pose any real threat to him.

Philosopher’s Approach to Starting the War

4. “You must know, then, that there are two methods of fighting, the one by law, the other by force: the first method is that of men, the second of beasts; but as the first method is often insufficient, one must have recourse to the second”

Since the beginning of politics, there has always been an actual misunderstanding. Negotiations will get you anywhere you want to go, and force is never the thing to do. Well… although it might be correct, it’s not always efficient.

Sometimes, political rulers have to be beasts and not always men, especially when dealing with other beasts or the first approach has failed.

5. “Wars begin when you will, but they do not end when you please.”

Machiavelli wasn’t always portraying the image of a cold-hearted human being who is numb to ideas such as war, loss of life, and uncontrollable use of force. Here is a prime example. It’s the most logical statement that you will probably find in this article, but it’s the truest and most accurate one.

With everything going on in the contemporary world, the quote is self-explanatory.

6. “Before all else, be armed.”

That’s another pretty self-explanatory statement too!

Machiavelli’s Deontology

7. “A battle that you win cancels all your mistakes.”

The reasoning behind this approach? That you will never be able to cover the love of the people for glory and power with any other action that is more of a peaceful path. You will never be able to make people remember you for something unfortunate. If you lost the war against a great enemy of your country, you can never correct that. And this goes both ways.

No matter how many things you did wrongfully in the past as a ruler, winning a war is avenging you for the rest of your political life. This is why some of the most potent and capable leaders have lost a battle and people forgot about them. They associate them with a negative notion in the same way that people might honor ruthless weak politicians who made the country glorious.

8. “So far as he is able, a prince should stick to the path of good but, if the necessity arises, he should know how to follow evil.”

The introduction covers this topic. It’s related to the use of power and war as a way of controlling your fate while at the same time respecting the demand for peace that people might have. Manage to let the people lose but while you are in power, let them believe that you won’t be unwilling to follow the evil route if you and your nation are in danger, either by your people or the enemy.

Machiavelli’s Myth

9. “Therefore, it is unnecessary for a prince to have all the good qualities I have enumerated. But it is very necessary to appear to have them.”

One of the controversial approaches we were talking about during the introduction. It’s strange to hear a political philosopher like Machiavelli supporting such a viewpoint. On the other hand, it’s true and the political world has confirmed it; the people getting to power don’t have to be the best.

They have to show and make the world believe they are the best. Politics is pretty simple. You have to know how to play the game. That entails learning how to break the rules effectively and without anyone noticing.

10. “The ends excuse the means.”

We are concluding with probably the most exciting thing you will learn today. Machiavelli never said that ‘the ends justify the means.’ He said that ‘the ends excuse the means.’

What’s the difference? In the case of the former, the result of the actions would be able to make the means right and not wrong; it would justify them. As far as it concerns the latter, the standards are always improper, even if the results are positive. Nonetheless, people can excuse the foul means. They cannot make them morally right.

Croce, Benedetto, 1925, Elementi di politica, Bari: Laterza & Figli.

Dietz, Mary G., 1986, “Trapping the Prince: Machiavelli and the Politics of Deception,” American Political Science Review, 80(3): 777–799. doi:10.2307/1960538

Dyer, Megan K., and Cary J. Nederman, 2016, “Machiavelli against Method: Paul Feyerabend’s Anti-Rationalism and Machiavellian Political ‘Science,'” History of European Ideas, 42(3): 430–445. doi:10.1080/01916599.2015.1118335

Von Vacano, Diego A., 2007, The Art of Power: Machiavelli, Nietzsche, and the Making of Aesthetic Political Theory. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Wood, Neal, 1967, “Machiavelli’s Concept of Virtù Reconsidered”, Political Studies, 15(2): 159–172. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.1967.tb01842.x