The idea that ancient builders could move stones heavier than jumbo jets without modern cranes or engines seems impossible at first glance. Yet across the world, enormous monuments like Baalbek’s temple platform, the walls of Sacsayhuamán, and Egypt’s unfinished obelisks stand as lasting evidence of extraordinary engineering. How ancient engineers moved stones that today would challenge even heavy machinery remains one of archaeology’s most enduring and fascinating questions.

How ancient engineers moved stones

New research over the past few years has added fresh insights into these mysteries, revealing just how much ancient civilizations knew about materials, labor, and physics — knowledge that continues to astonish modern experts.

The incredible stones of Baalbek

In Baalbek, Lebanon, the ruins of the Temple of Jupiter are built on some of the largest stones ever used in construction. The most famous, the so-called “Stone of the Pregnant Woman,” weighs approximately 1,000 tons. In 2014, archaeologists uncovered an even larger block nearby, still partially buried, weighing an estimated 1,650 tons. For comparison, a fully loaded Boeing 747 can weigh up to about 400 metric tons. Some of these stones are more than four times heavier.

The question of how these stones were quarried, transported, and precisely placed without the benefit of industrial equipment remains unsolved. However, recent theories suggest that a combination of simple but effective methods could have been used. Archaeologists believe that the stones were shaped carefully at the quarry site itself, reducing the need for complex transportation over long distances. From there, ancient builders may have created massive earthen ramps to allow the blocks to be dragged or slid into place.

Labor forces likely numbered in the thousands, and new experimental studies show that lubrication — using water, oil, or clay on pathways — dramatically reduces friction, making it feasible to move enormous loads with coordinated team effort. Though no definitive proof has surfaced, the emerging picture is one of methodical planning, not magic. It was not a single “lost technology” but a combination of well-understood techniques, enormous manpower, and careful preparation.

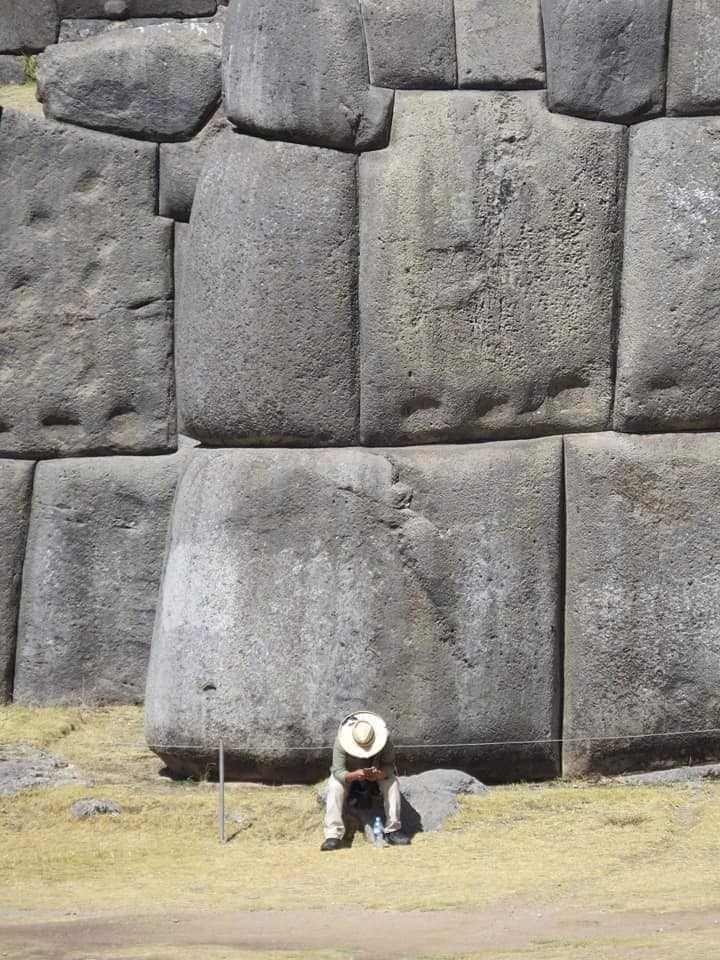

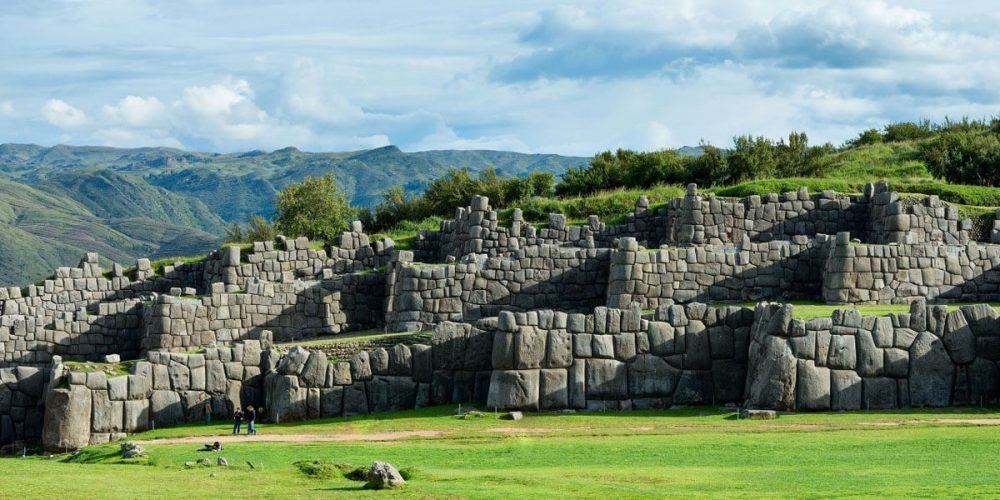

Sacsayhuamán and the mystery of perfect fits

Thousands of miles away in Peru, the ancient fortress of Sacsayhuamán presents a different but equally stunning mystery. High above Cusco, massive limestone blocks — some weighing over 120 tons — are fitted together so precisely that even a knife blade cannot be inserted between them. The stones are irregularly shaped, yet they lock together perfectly, providing seismic resistance that has helped the walls survive countless earthquakes over the centuries.

Studies suggest that the stones were quarried several kilometers from the construction site, shaped using harder stones as tools, and transported across challenging Andean terrain. Despite the absence of the wheel for heavy loads in the Incan world, builders likely used ramps, sledges, and rolling methods combined with ingenious use of manpower and an intimate understanding of balance, gravity, and material properties.

Recent archaeological work, particularly field studies completed between 2020 and 2024, has revealed that traces of quarry roads and prepared transportation paths are more extensive than previously thought. These findings support the idea that Sacsayhuamán was not a miracle of unknown technology, but a triumph of careful planning, adaptive techniques, and extraordinary labor coordination.

Lessons from Egypt’s unfinished obelisk

In Egypt’s ancient granite quarries at Aswan, a single stone reveals more about ancient engineering than any other: the unfinished obelisk. Still attached to the bedrock, it lies cracked and abandoned — a frozen moment in time that offers a rare glimpse into construction practices otherwise lost to history.

Had it been completed, the obelisk would have stood about 42 meters tall and weighed an estimated 1,200 tons, making it the largest known stone ever intended to be quarried by human hands. For comparison, it would have been almost twice as heavy as any of the blocks at Baalbek.

What makes this site extraordinary is the presence of visible tool marks and quarrying methods. Archaeologists have found that workers used dolerite pounding stones, harder than the granite itself, to carve deep trenches along the sides of the obelisk. The surfaces are pitted with thousands of impact scars where hammerstones chipped away the rock bit by bit.

Some researchers suggest that the workers might have combined mechanical hammering with heating techniques, such as lighting controlled fires to fracture the granite along specific lines. Once enough space was created around the obelisk, it would have been detached from the bedrock, likely using wooden levers and wedges.

Yet the real challenge would have come next: moving the massive stone from the quarry to the Nile, and then to its intended temple site. Ancient tomb paintings depict sledges being dragged across lubricated tracks, with laborers pouring water in front of the runners to reduce friction. Experiments carried out in the 21st century have shown that wetting the sand can halve the effort needed to pull heavy sledges, offering practical validation of these ancient depictions.

However, no sledges, winches, or lifting devices from the Old Kingdom have survived, leaving historians to rely on clues and inference. The exact methods for loading such a massive object onto riverboats — and the designs of those boats themselves — remain speculative. Could vessels of wood and rope construction really have borne the weight of an obelisk over a thousand tons? If so, how were they reinforced against splitting or sinking?

The unfinished obelisk stands today not as a failure, but as a rare survival of an ancient engineering attempt interrupted mid-process. It reminds us that these colossal achievements were not guaranteed, and that even the greatest builders faced setbacks that left mysteries for us to ponder thousands of years later.

The enduring mysteries that defy easy answers

Even after decades of research, no single theory fully explains how ancient civilizations moved stones heavier than today’s largest aircraft. Instead of one lost technique, we see glimpses of many: quarry-side shaping, massive earthen ramps, wooden sledges sliding over wetted tracks, and perhaps ingenious use of levers and rollers. But questions remain.

At Giza, some granite blocks weighing over 20 tons were transported from Aswan, more than 800 kilometers away. Archaeologists believe they floated them down the Nile on massive boats — yet the exact designs of these vessels are still unknown. Could they truly have borne such weight without sinking? No ancient boat large enough has ever been found.

At Sacsayhuamán, in the thin air of the Andes, the fitting of colossal stones without mortar continues to puzzle engineers. How did they lift and position blocks so perfectly, across rugged mountain terrain, without the wheel or draft animals?

Other sites raise equally fascinating questions. In Japan, the megaliths of Ishibutai Kofun hint at advanced lifting techniques. In Easter Island, the moai statues — some weighing over 80 tons — were somehow moved across rough volcanic landscapes. Each culture, in its own way, unlocked physical secrets we still struggle to fully understand.

What binds all these mysteries together is not a lost super-technology. Human brilliance is applied in ways adapted to time, place, and challenge. They planned, adapted, experimented, and persevered.

Today, we can only stand in awe. These builders moved the immovable, shaped the unshapable, and dared to create monuments that outlast empires. Perhaps the real mystery is not how they moved these stones, but how they believed they could in the first place.