At first glance, the ancient Chinese and Maya civilizations couldn’t be more different — separated by vast oceans, isolated by time, and shaped by their own distinct environments. But archaeological work in Honduras has reignited an old question: could the ancient Chinese and Maya similarities hint at something deeper, possibly even a shared cultural ancestry?

Ancient Chinese and Maya similarities?

This idea isn’t just speculation. And it also does NOT mean that these two ancient civilizations had contact in ancient times. But what is a fact is that Chinese archaeologists working at the ancient Maya site of Copán have uncovered sculptures and architectural features that closely resemble those of China’s Neolithic Liangzhu Culture, particularly in terms of symbolic decorations and mythical creatures. Among the most striking parallels are depictions of the feathered serpent god Kukulkan, which bear a resemblance to ancient Chinese dragon imagery — both powerful symbols connected to sky, water, and divine authority.

These discoveries have renewed interest in the “China-Maya continuum” — a concept proposed in the 1980s by Chinese-American archaeologist Kwang-Chih Chang. He suggested that both cultures might share shamanistic roots dating back to Paleolithic ancestors, long before the rise of formal states. While Chang never claimed direct contact, he believed these ancient echoes of belief and ritual could leave visible traces in art, cosmology, and symbolism.

More recently, archaeologists have noted additional similarities. One example is the Maya calendar, which bears conceptual resemblances to the Chinese calendrical system, specifically the 10 Heavenly Stems and 12 Earthly Branches. Both systems reflect a cyclical view of time — a rare feature in early civilizations and one that may point to deeply rooted, shared cosmological ideas.

Migration, Not Communication

According to Li Xinwei, lead archaeologist from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), there’s still no evidence of direct contact between the two ancient civilizations. Instead, the similarities may be the result of shared Paleolithic ancestry. Early humans who migrated across the Bering Strait from northern and eastern Asia into the Americas some 15,000 years ago may have carried with them certain cultural traits — oral traditions, symbols, and spiritual beliefs — which then evolved independently into what we now recognize as the Chinese and Maya civilizations.

Li emphasized that these findings don’t suggest cultural borrowing or diffusion across oceans, but rather parallel evolution from common ancestral roots.

Copán: A Meeting Ground of Ideas

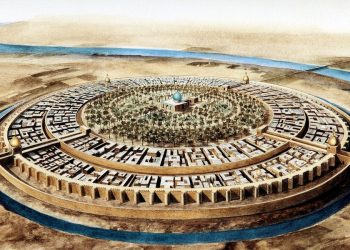

The site of Copán, often referred to as the “Athens of the Maya world,” has become a focal point for this line of inquiry. Long known for its intricate stonework and ceremonial architecture, Copán has now yielded even more fascinating material under the care of the Chinese archaeological team.

Working at a 4,000-square-meter residential complex once home to local aristocracy, the Chinese team uncovered a large royal tomb and symbolic motifs such as crossed torches — imagery linked to Maya kingship. Their analysis of jade relics, depictions of the lightning god Kawiil, and regional building layouts has further highlighted the sophistication of this ancient city, and its potential connection — however remote — to distant civilizations.

The ancient Chinese and Maya similarities challenge how we think about cultural development. They remind us that human creativity, myth-making, and ritual often follow similar paths — even when separated by oceans and millennia. And while the connections may not point to direct communication, they hint at something even more profound: a shared symbolic language stretching back into prehistory.

Additionaly, According to Xinwei, genetic studies have revealed that both the ancient Chinese and Mesoamerican peoples may share distant ancestry — a deep-rooted connection that predates the rise of their civilizations. What fascinates researchers is how this shared foundation could give rise to two remarkably advanced yet geographically isolated cultures. Li suggests that understanding how groups with common cultural genes followed such different evolutionary paths — and still arrived at similar spiritual, architectural, and calendrical systems — opens a new chapter in the study of global ancient history.