You’ve heard the story of Egypt’s pyramids. Majestic stone giants rising from the sands of Giza, said to be tombs for the pharaohs. Yet despite over a century of exploration, no pharaoh has ever been found inside the Great Pyramid, nor in the other two. These iconic structures continue to puzzle archaeologists and historians alike.

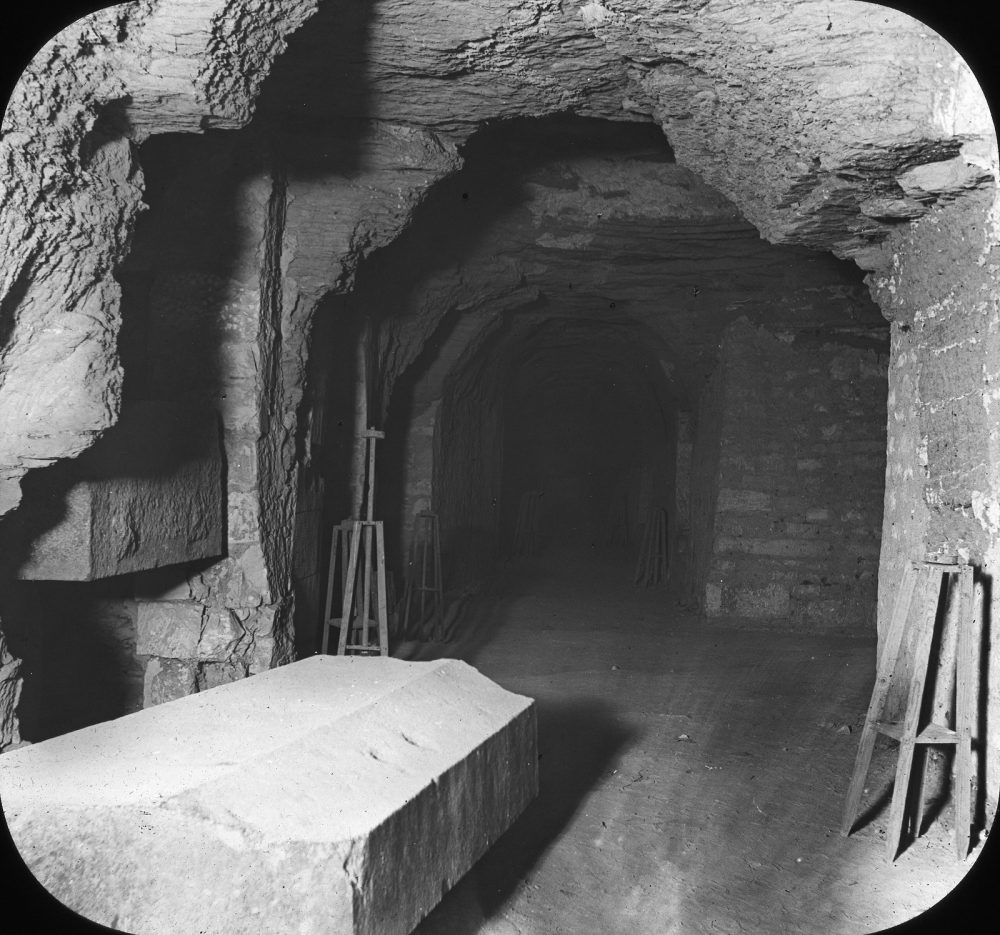

But just south of Giza, buried beneath the desert at Saqqara, lies a site that raises even more questions. Beneath the surface is a dark, silent corridor carved into limestone. Lining its sides are massive granite coffins, each weighing up to 80 tons. There are no mummies inside. No names. This is the hidden chamber of giant sarcophagi — a mystery that Egyptologists still cannot fully explain. And it is called the Serapeum of Saqqara.

A hidden chamber of giant sarcophagi: the Serapeum of Saqqara

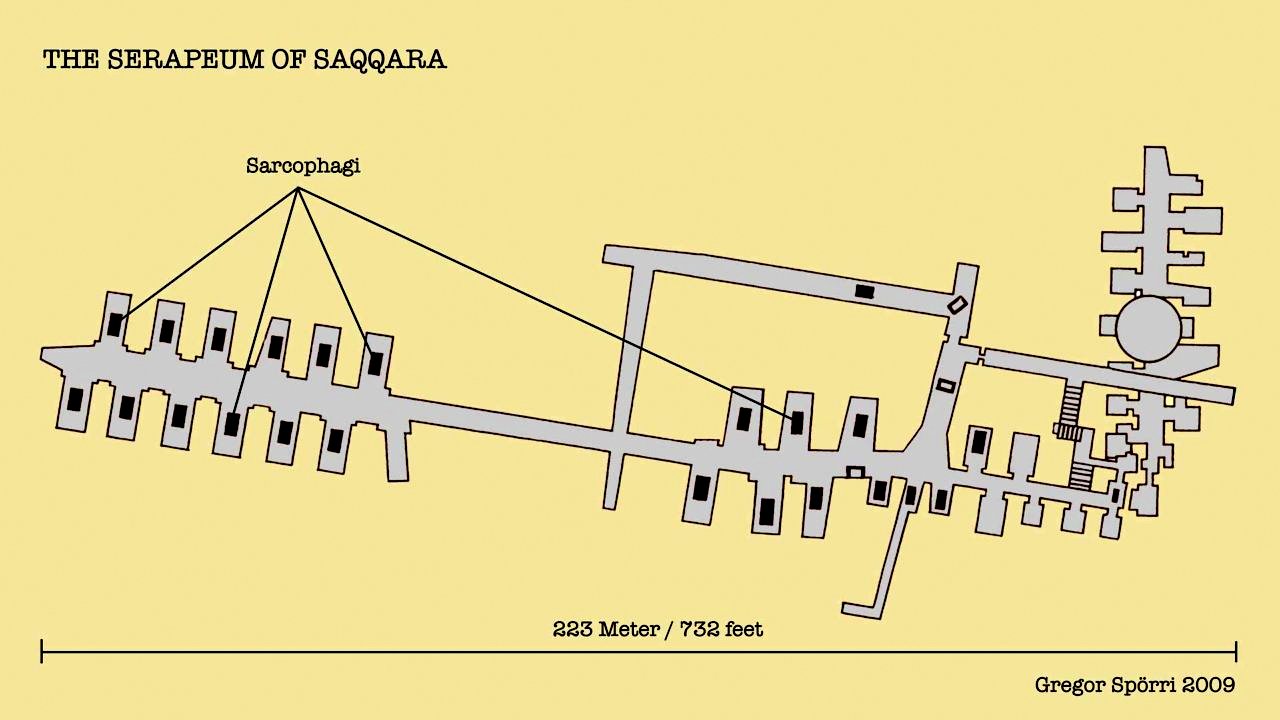

The Serapeum is located in the ancient necropolis of Saqqara, not far from the Step Pyramid of Djoser, which is believed to be the oldest known pyramid in Egypt. The site was first excavated in 1850 by French archaeologist Auguste Mariette, who followed clues from ancient texts describing burials of sacred bulls.

What he found shocked even the experts of his time. A long subterranean tunnel, more than 100 meters in length, with side chambers carved into the limestone walls. Inside those chambers rested 24 enormous sarcophagi made of solid granite and basalt. They were smooth, polished, and almost entirely unmarked.

According to traditional interpretations, the Serapeum was a burial place for the Apis bulls — animals considered sacred and believed to be earthly incarnations of the god Ptah. When an Apis bull died, it was embalmed and buried with rituals worthy of royalty. The site was in use for centuries, with burials spanning multiple dynasties, especially around the 13th century BCE.

While inscriptions and evidence of Apis bull burials exist in earlier sections of the Serapeum, the main chamber that holds the largest sarcophagi is mostly unmarked. Only four of the twenty-four boxes include any inscriptions, and most contain no remains or only fragments. None display royal seals, and nearly all are completely anonymous.

The sarcophagi: size, material, and unanswered questions

Each sarcophagus in the Serapeum is a technical and logistical marvel. Carved from single blocks of solid stone, many were made of granite or basalt. Several archaeological sources, including site studies and Egypt tour literature, suggest that much of the granite was quarried in Upper Egypt, most likely in the region of Aswan, known since antiquity for its high-quality red granite. Transporting these blocks nearly 800 kilometers to Saqqara, then lowering them into an underground labyrinth, remains one of the greatest engineering feats of the ancient world.

Each sarcophagus weighs between 60 and 80 tons, and some of the lids are estimated to weigh as much as 25 to 30 tons. The sheer scale alone would have required careful planning, skilled labor, and a method of transportation capable of moving massive stone over long distances. The mainstream view holds that workers used barges to float the stones up the Nile before hauling them overland to Saqqara. From there, they would have needed ramps, sledges, and perhaps water to reduce friction as the boxes were lowered into the underground vault.

Once in place, the craftsmanship displayed is difficult to ignore. The interior walls of the sarcophagi were hollowed out with precision, their surfaces polished to a smooth finish. In some cases, the interiors reflect light. The joints between lid and base are so perfectly aligned that they appear almost seamless. Engineers and stoneworkers continue to examine how such work could have been done using the copper tools typically associated with the time.

What makes these sarcophagi even more puzzling is their anonymity. Unlike most Egyptian tombs, which feature hieroglyphs, prayers, names, or funerary art, the majority of these granite boxes are completely bare. Only four out of the twenty-four discovered in the main chamber bear any inscriptions at all, and those are inconsistent in quality. Bear in mind that some seem to be professionally engraved, others crudely scratched, possibly added long after the boxes were built.

The Serapeum of Saqqara presents a unique archaeological enigma. While it was the designated burial site for the sacred Apis bulls, many of its massive granite sarcophagi were found empty or contained only minimal remains.

Out of the 24 surviving sarcophagi, only four bear inscriptions, leaving the majority unmarked. This absence of identifying information is particularly intriguing, considering the ancient Egyptians’ detailed burial customs, which often included extensive inscriptions and rituals to honor the deceased and ensure their journey to the afterlife. The silence of the Serapeum’s sarcophagi continues to challenge our understanding of ancient Egyptian funerary practices and beliefs.

How were they transported and placed underground?

One of the biggest questions, and one of my favorite.

Moving a single 70-ton sarcophagus carved from granite would be difficult even with today’s equipment. At the Serapeum, workers managed to transport more than twenty of them into narrow underground corridors cut into limestone. These passageways are just wide enough to fit the boxes, leaving little room for error. How this was done over 2,000 years ago remains one of the most difficult questions in Egyptian archaeology.

The most widely accepted view is that the sarcophagi were pulled on wooden sledges across prepared paths. Ancient artwork shows similar methods used for statues and stone blocks. To make the haul easier, workers may have poured water onto the sand or mud under the sledges to reduce friction. Once inside the tunnel system, the burial chambers were likely filled with sand. By slowly removing the sand, workers could lower the sarcophagus into place with control and stability.

This method could work, but it would have required coordination, precise planning, and a large labor force. The smallest mistake during transport could damage the stone or block the passage entirely.

The carving of the granite poses another challenge. At the time, Egyptian tools were made of copper, dolerite, and quartz-based abrasives. Using these, workers could pound, saw, and grind the granite, but the process was extremely slow. Some of the sarcophagi in the Serapeum have mirror-like finishes inside, with clean lines and sharp edges that suggest a high degree of care. Modern experiments have shown that similar results can be achieved with sand and repetitive effort, but it can take weeks or even months to shape a single surface.

What continues to puzzle researchers is the purpose behind this effort. Most of the sarcophagi are completely unmarked. They contain no names, no hieroglyphs, and no decoration. Many were found empty. For a culture that often covered tombs in prayers and symbols for the afterlife, this silence is hard to explain. The builders had the skill to make these coffins extraordinary but left behind no message to tell us why.

Were these sarcophagi really made for bulls — or were they built for something else?

According to mainstream Egyptology, the massive granite sarcophagi in the Serapeum were intended for the burial of Apis bulls. These animals were considered sacred in ancient Memphis, and believed to be living manifestations of the god Ptah. When one died, it was embalmed, wrapped in linen, and buried with ritual honors. Several known Apis bull burials have been discovered at Saqqara, and some of the older tunnels within the Serapeum do contain inscriptions and remains consistent with this practice.

But the theory does not explain everything.

Many of the largest sarcophagi in the main vault were found empty. Others held only bone fragments or material too deteriorated to confirm what had once been inside. The boxes themselves are massive, much larger than what would be needed to hold a fully grown bull and any accompanying burial items. Even more puzzling is the total lack of decoration. In ancient Egypt, even the simplest tombs were typically inscribed with names, prayers, protective texts, or images of the person buried. These granite coffins have none of that. Most are completely blank, carved and polished with great care, then sealed and left without a single word.

Here are a couple of questions that I have asked… If these were truly used for the burial of sacred animals, why are they anonymous? If they were never used, why go to such extraordinary lengths to build and install them?

Now I might add that questions like these have opened the door to other interpretations. Some researchers have suggested that the sarcophagi may have been made for high-ranking individuals, not animals and that their names were either removed intentionally or never inscribed. Others believe the coffins served symbolic or ceremonial purposes unrelated to physical remains. They may have represented containers for something sacred or even served as cenotaphs.

Cenotaphs are basically empty tombs meant to honor an unseen presence.

A more controversial view suggests that the Serapeum is much older than we think. Now, according to this idea, the Apis cult may have reused an existing structure, and the sarcophagi were originally made for reasons lost to history. Supporters of this theory often point to the precision and scale of the workmanship as something that exceeds what should have been possible with the known tools of the time.

These alternative ideas remain on the fringe, and most scholars approach them with caution. But even among Egyptologists, there is no full agreement about how or why the largest sarcophagi were made. The site raises more questions than it answers.

What makes this hidden chamber so unique

When most people think of ancient Egypt, they picture the pyramids of Giza. These massive stone structures rise above the desert and have come to symbolize the entire civilization. For generations, they have been called tombs. Yet to this day, not a single royal mummy has been found inside the Great Pyramid, nor in the pyramids of Khafre or Menkaure. This absence has led many scholars to question long-held assumptions about their original purpose.

The Serapeum at Saqqara presents a different kind of mystery. Unlike the pyramids, it is hidden beneath the surface, cut deep into the rock. There are no grand facades, no towering monuments, and almost no inscriptions. What it holds instead are enormous granite sarcophagi, carved with exceptional skill and placed with care, but left almost entirely anonymous.

The Serapeum of Saqqara remains an enigmatic site. While it is traditionally considered the burial place for the sacred Apis bulls, the main chamber’s massive granite sarcophagi present several mysteries. Many of these sarcophagi lack inscriptions, names, or recorded rituals that would typically accompany such significant burials in ancient Egypt. This absence of identifying information is unusual, given the Egyptians’ meticulous burial practices and the importance they placed on the afterlife.

There are no clear instructions from the past explaining what these boxes were for or why they were made so large. The engineering behind them is impressive, but the purpose remains unknown.

This silence is what draws attention. Most Egyptian tombs speak clearly. They name the dead, describe their lives, and ask for safe passage into the afterlife. The Serapeum does none of this.

What was meant to be placed inside these coffins? Who ordered them to be made? Why were they buried so carefully, and then left unmarked? The answers have not been found. Until they are, this hidden chamber remains one of the most interesting places in the history of ancient Egypt.