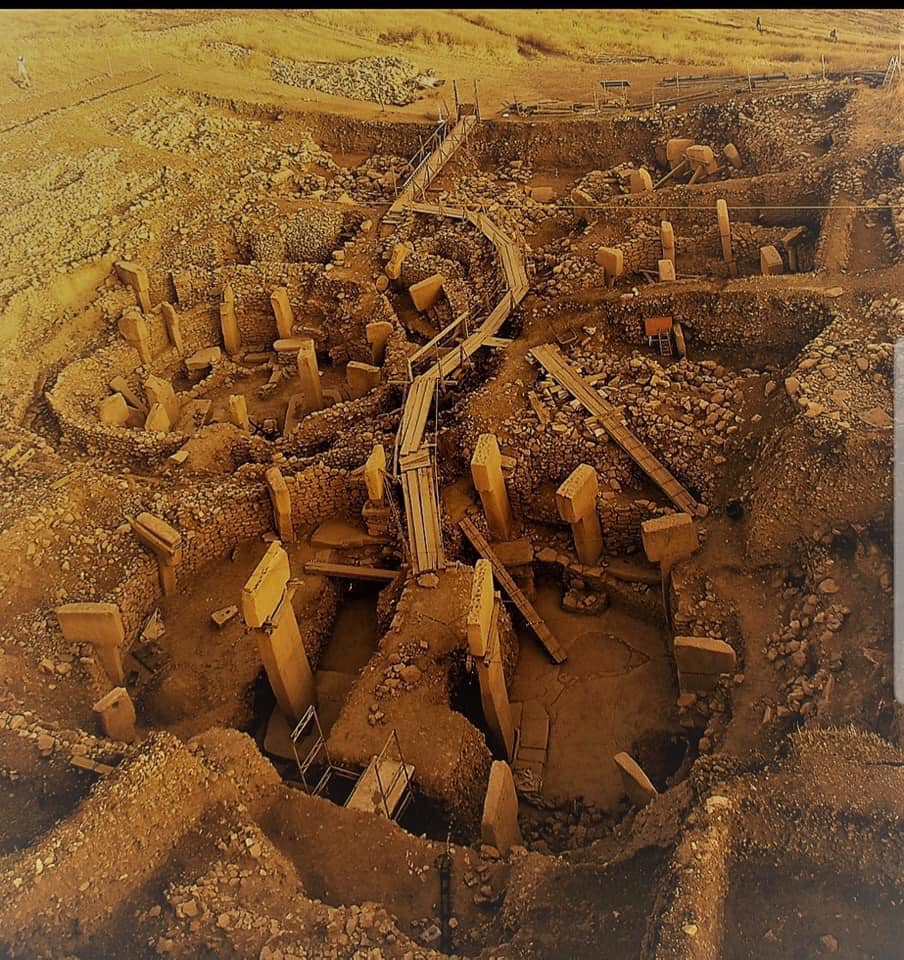

Göbekli Tepe is one of the most remarkable ancient sites on Earth, and it stands out not only because of its age but also because its very existence challenges our understanding of history. The intricate carvings found at this 12,000-year-old monument in Turkey may mark solar days and years, potentially making it the oldest solar calendar ever discovered.

Recent research suggests that these carvings could represent a system for tracking time, with symbols marking significant astronomical events, including the summer solstice. If these interpretations are correct, this would place the calendar thousands of years ahead of any other known solar calendar, offering new insights into early human civilization.

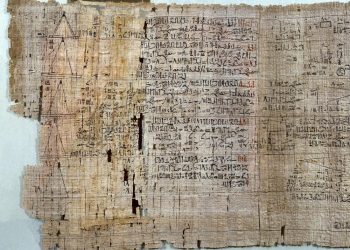

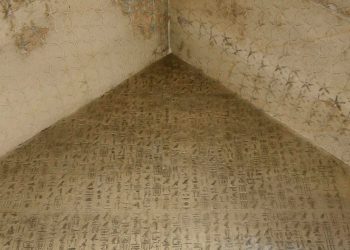

A study published in Time and Mind by researchers from the University of Edinburgh explores this possibility in detail. They propose that the repeated “V” shapes carved onto the pillars at Göbekli Tepe might represent individual days, with one pillar even accounting for 365 days. The summer solstice, in particular, seems to be highlighted by a “V” around the neck of a bird-like figure, indicating its importance to the ancient observers.

The implications of these findings are profound. The researchers suggest that the inhabitants of Göbekli Tepe were keen sky watchers, possibly motivated by a catastrophic comet strike around 10,850 B.C., which may have triggered a mini-ice age. This event could have spurred the development of new religious practices and agricultural advancements as the community sought to adapt to the changing climate.

In addition to tracking solar movements, the carvings at Göbekli Tepe appear to record lunar cycles, predating other known calendars by millennia. The researchers also hypothesize that these ancient people may have had an early understanding of Earth’s interaction with comet fragments, a concept confirmed by modern science.

To support their theory, the team points to another pillar at the site that seemingly illustrates the Taurid meteor stream, believed to be the source of the ancient comet strike. This suggests that the ancient civilization was not only recording the passage of time but doing so with remarkable precision, long before the advancements of later civilizations such as ancient Greece.

The discoveries at Göbekli Tepe raise compelling questions about the origins of timekeeping and the sophistication of early human societies. Whether this monument truly represents the world’s oldest solar calendar remains a topic of debate, but it undeniably offers a fascinating glimpse into the minds of our ancient ancestors.