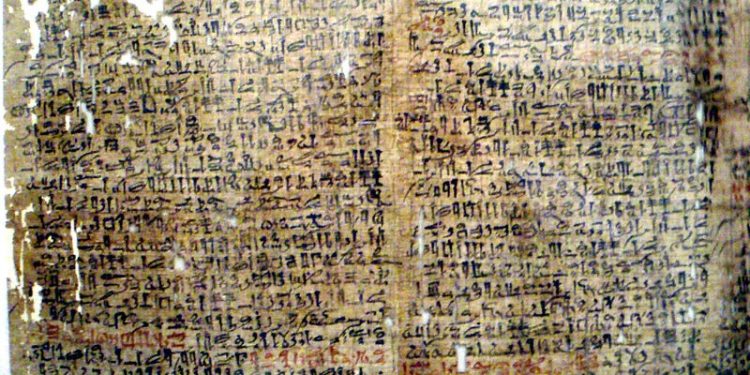

Ancient Egyptians loved their stories. Storytelling was a big part of their everyday life and we can clearly see that in the countless papyri and artifacts found in the past couple of centuries.

When it comes to ancient Egyptian storytelling, no document goes further back than the Westcar Papyrus known for its magical stories.

So long after its discovery, we still know almost nothing about the origin, purpose, and nature of the papyrus, but one thing is for certain – it was one of the reasons for the uprising interest in Ancient Egypt.

1. The Westcar Papyrus is known as the oldest collection of stories

The Westcar Papyrus is at least 3500 years old. Historians claim that it was created during the Second Intermediate Period of Ancient Egypt or some time between 1782 – 1570 BC making it the oldest example of such papyri.

2. The Westcar Papyrus consists of five stories

The Westcar Papyrus contains five stories written in twelve columns with priestly signs. According to the text, the stories were told in front of the royal court of Pharaoh Cheops by his sons. That is why the actual stories are dated to the time of the fourth dynasty of Ancient Egypt, a period known as the “Golden Age” of the Old Kingdom.

3. All stories revolve around magic and enchantment

Each of the stories is filled with magical and miraculous events. Each vignette describes the actions of priests or magicians from the period of the 4th Dynasty.

4. The first story is almost entirely gone

The Westcar Papyrus is surprisingly intact as a whole apart from the first story. Only several lines in the beginning and the end remain which were enough for historians to understand the subject of the story.

5. Due to the nature of the stories, they are believed to have been propaganda in favor of the kings of Egypt

Knowing that the stories include a fair amount of magic and enchantment, there is a theory that suggests that they were created sometime between the Second Intermediate Period and the Third Intermediate Period to legitimize the power of the pharaohs.

In other words, the theory suggests that there is little truth in the actual stories and we can consider them as fairy tales.

6. The Westcar Papyrus was further damaged by archaeologists

Archaeology in the early 19th century was not as advanced which lead to numerous occasions of damaged artifacts. One such artifact was the Westcar Papyrus which allegedly was damaged by archaeologists who tried to preserve it using wrong techniques.

7. Henry Westcar never mentioned anything about the discovery

We now know that Henry Westcar discovered the papyrus in 1824 but it remained a mystery for several decades. It is unknown why he hid his discovery but it is a fact that he did not mention it on any occasion and did not write about it in any of his journals.

8. The papyrus could potentially be a copy of an older document

The papyrus itself was written in much lower quality handwriting than most ancient papyri that are found. Moreover, it is full of errors that you wouldn’t normally see in an official document. This has led to the theory that it may have been made by a student who copied it from another original document.

9. The Westcar Papyrus was written on an old papyrus

Another reason why historians believe that it is not the work of a professional is the actual papyrus scroll that it was written on.

Research and examinations have found signs of a previous document underneath the writing we see today. This means that it was written over a previous text which was a common practice in Ancient Egypt since papyrus scrolls were expensive materials.

10. The Westcar Papyrus is now on display at the Berlin Museum

The Westcar Papyrus has been on display at the Berlin Museum since the end of the 19th century after it became an actual subject of interest and was translated in German for the first time.