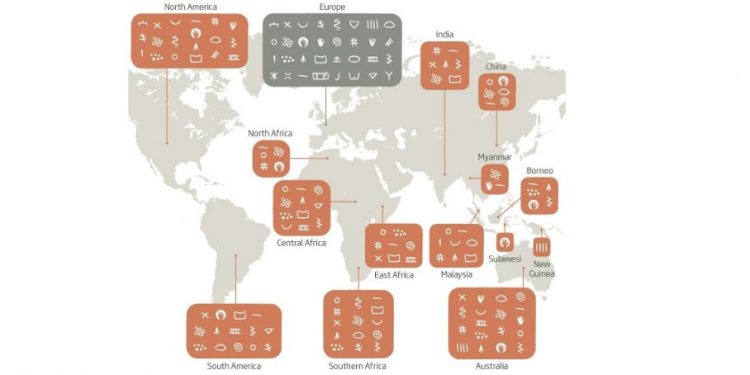

The idea that cave symbols form a global language isn’t just speculative anymore. Ancient cave symbols found across Ice Age Europe may be more than primitive art—they could represent the earliest form of human communication, predating written language by tens of thousands of years.

Are ancient cave symbols the first traces of a global language?

For decades, scholars have agreed that the world’s first writing system emerged in ancient Sumer around 3,400 BC. But what if that timeline is wrong—or at least incomplete? New research suggests that ancient cave symbols from around 40,000 years ago may actually represent the earliest known form of symbolic communication, one that may have spread across continents before the first cities were ever built.

That’s exactly what paleoanthropologist Genevieve von Petzinger is investigating. Working out of the University of Victoria in Canada, von Petzinger has spent years documenting prehistoric cave markings—specifically, 32 recurring geometric symbols found in Ice Age cave art across Europe. These aren’t animal drawings or figurative art, but abstract signs: zigzags, triangles, crosses, grids, dots, and stencils.

And they show up everywhere.

From France to Spain, from southern Europe to as far as Africa, the same symbols appear again and again, carved or painted onto cave walls as early as 40,000 BC. According to von Petzinger, this repetition points toward something deliberate—perhaps even a proto-writing system that existed long before anything resembling formal script.

A prehistoric code hidden in plain sight

In her groundbreaking book The First Signs: Unlocking the Mysteries of the World’s Oldest Symbols, von Petzinger argues that these markings are far more than decoration or ritual scrawlings. She believes they may represent a kind of symbolic “code”—a mental dictionary passed down through generations of early Homo sapiens as they migrated from Africa into Europe and beyond.

“This does not look like the start-up phase of a brand-new invention,” she explains. The widespread use of these 32 consistent ancient cave symbols suggests that they were part of a shared system—perhaps the very foundation of written communication as we know it.

Between 2013 and 2014, von Petzinger traveled to over 50 Paleolithic cave sites in France and southern Europe. She meticulously catalogued every symbol she encountered, paying close attention to how the signs were arranged and repeated. Her research revealed distinct patterns: for example, hand stencils frequently appear alongside dot clusters, especially in artwork dated to 40,000 BC.

Other forms—like Penniforms, or feather-shaped marks—start appearing around 26,000 BC in northern France before spreading west into Spain and Portugal. This progression suggests not only symbolic meaning, but also evolution, as if early humans were refining how they communicated visually across generations.

Could early humans have shared a symbolic language?

The idea of a cave symbols global language may sound radical—but it’s gaining traction. Francesco d’Errico, an archaeologist at the University of Bordeaux, points to evidence that symbolic expression predates even Homo sapiens. A zigzag carved into a shell by Homo erectus in Java 500,000 years ago may be the earliest known example of deliberate symbolic behavior.

“The ability of humans to produce a system of signs is clearly not something that starts 40,000 years ago,” d’Errico says. “This capacity goes back at least 100,000 years.”

This suggests that early humans—and possibly their hominin ancestors—may have used symbolic markings to communicate ideas, concepts, or identity long before formal writing systems emerged.

And if von Petzinger is correct, it means that many cave symbols weren’t isolated expressions. Instead, they may be the fragments of a lost symbolic system that spread across continents—an early visual language that connected distant groups of humans long before trade, roads, or cities.

What were these ancient messages trying to say?

While von Petzinger stops short of calling these symbols a “language” in the linguistic sense, the implications are enormous. The fact that specific combinations of signs appear repeatedly suggests intention and consistency. In some ways, they resemble early alphabets—compressed systems designed to store and transmit meaning.

What did they mean? That remains a mystery. But many of the symbols appear in consistent pairings or sequences, suggesting rules or syntax. Some may have represented names, places, rituals, seasons, or even instructions. Others may have served as clan symbols or territorial markers.

What’s clear is that prehistoric humans weren’t simply painting for the sake of art—they were communicating.

As more caves are explored and more ancient markings are documented, researchers may someday piece together a fuller picture of what these early humans were trying to say. For now, these symbols stand as a bridge between visual art and written language—a reminder that the history of human communication is far older and more complex than we once believed.