Ancient civilizations left behind stone structures so precise and so massive that they still baffle modern engineers. These weren’t just heavy blocks stacked into place, some were carved with smooth finishes, perfect symmetry, and angles that rival today’s machine work. From Egypt to India, the evidence points to ancient stone-cutting secrets we still haven’t figured out.

How did they shape granite boxes with mirror-flat faces? How did they carve temples into single mountains? And how did they create interlocking stone blocks so perfect that not even a razor blade fits between them?

Let’s take a closer look at four of the most mysterious sites in the world.

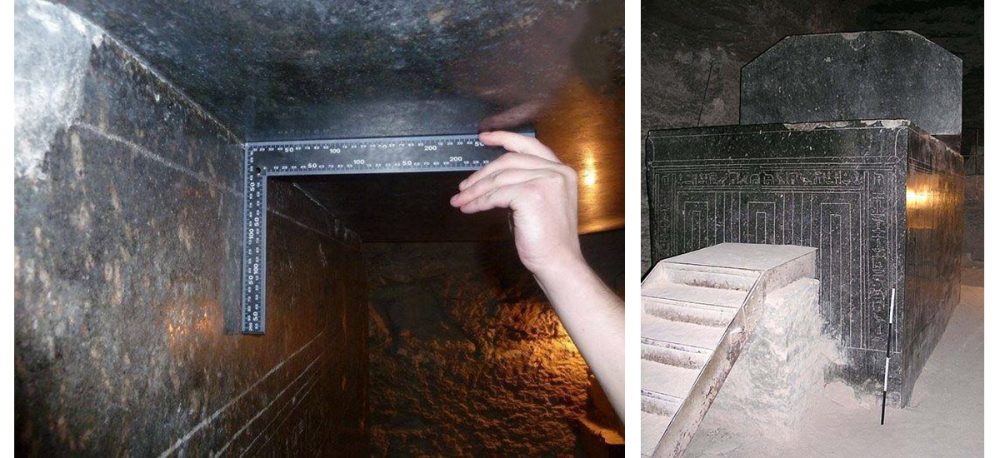

The Serapeum of Saqqara reveals ancient stone-cutting secrets in Egypt

Hidden beneath the sands of Egypt lies the Serapeum of Saqqara, a network of underground tombs that hold 24 massive granite sarcophagi. Each one weighs up to 70 tons and was carved with astonishing precision.

The granite used for these boxes came from Aswan, more than 500 kilometers away. Transporting these blocks was a feat in itself. And even some of the stones used to build the Great Pyramid of Giza came from Aswan. Anyway, what puzzles engineers most is how the ancient builders shaped them. The corners are razor-sharp. The interiors are polished flat. Tool marks are rare, and when they appear, they don’t match what we’d expect from primitive copper chisels.

Some researchers believe abrasive slurries were used, while others suggest lost tools or methods that we no longer understand. Whatever the case, the Serapeum offers some of the strongest evidence of ancient stone-cutting secrets that remain unsolved. Oh and, it is also one of my favorite sites from ancient Egypt.

Puma Punku shows laser-like precision

In the highlands of Bolivia, at the site of Puma Punku, lies another mystery carved in stone. The site features blocks made of diorite and andesite, which by the way are materials nearly as hard as diamond. Yet the stones are shaped with 90-degree angles, straight channels, and perfect joins.

Some blocks at Puma Punku resemble puzzle pieces. They interlock with such precision that they seem machined. The cuts are clean and consistent, and in some cases, tiny drill holes suggest advanced boring methods.

How did the builders cut such hard stone with no steel tools? And how did they move and position the blocks so that they fit perfectly, without mortar? These questions remain central to the study of ancient stone-cutting secrets. How did the ancient builders achieve such precision? When looking at some of the stones, they almost seem as if they were shaped and worked on by a laser. Now obviously that was not the case, which leads me to question if there are certain techniques from Puma Punku that were lost in time and we no longer understand.

Kailasa Temple in India is an ancient masterpiece

At Ellora in Maharashtra, India, the Kailasa Temple rises from the bedrock, not built, but carved from a single mountain. This massive temple was excavated from the top down. Entire halls, columns, staircases, and statues were carved into place with remarkable symmetry.

Archaeologists estimate that over 200,000 tons of stone were removed during the temple’s creation. But how they did it remains unclear. No inscriptions describe the process. No tools have been found nearby. And no known method could explain the speed and accuracy needed to complete the structure in a reasonable timeframe.

The Kailasa Temple represents one of the most stunning examples of ancient stone-cutting secrets. It’s not just the scale, but the planning, the design, and the flawless execution that make it so extraordinary and blows my mind.

Yangshan Quarry reveals a project that could never be completed

In China, near the city of Nanjing, lies the Yangshan Quarry. It holds the largest known unfinished stone project in the world, a stele base weighing more than 16,000 tons. The block was partially carved from the mountain, but never removed.

Why? Likely because once they finished cutting it, they realized it would be impossible to move. The size alone makes it unmanageable, even with today’s technology.

But the story doesn’t end there. The quarry shows signs of precise shaping and leveling. The fact that the builders began such an ambitious project suggests they either overestimated their capabilities, or had access to methods and knowledge now lost to time.

Are these sites proof of ancient lost knowledge?

Many traditional explanations involve copper chisels, hammers, and patience. But these theories fall short when faced with hard stones like granite and diorite. Modern tests have shown that copper tools wear down quickly and cannot create the clean finishes seen in ancient sites.

Alternative theories suggest the use of vibration-based cutting, high-speed drills, or abrasive compounds. Others speculate that we’ve lost entire branches of ancient engineering knowledge.

What is certain is that ancient stone-cutting secrets continue to resist simple answers. These sites raise serious questions about what early civilizations knew — and how much we’ve forgotten.

Until the secrets are revealed, the mystery remains

Despite decades of study, no modern team has successfully replicated what ancient builders achieved with the tools we’re told they had. The precision, scale, and execution seen at places like Saqqara, Ellora, and Puma Punku continue to challenge both engineering logic and archaeological theory.

These structures were not trial-and-error attempts. They required planning, knowledge of geometry, and a level of control over stone that suggests either a lost technique or a very different understanding of material science.

Until those methods are identified through evidence—not speculation—the question remains open. Were these builders simply far more advanced than we give them credit for? Or are we missing an entire chapter of human history?

Whatever the answer, one thing is clear. The ancient stone-cutting secrets scattered across the globe deserve serious, open-minded investigation. They are not just puzzles from the past. They may be the key to understanding who we were—and how much we’ve forgotten.