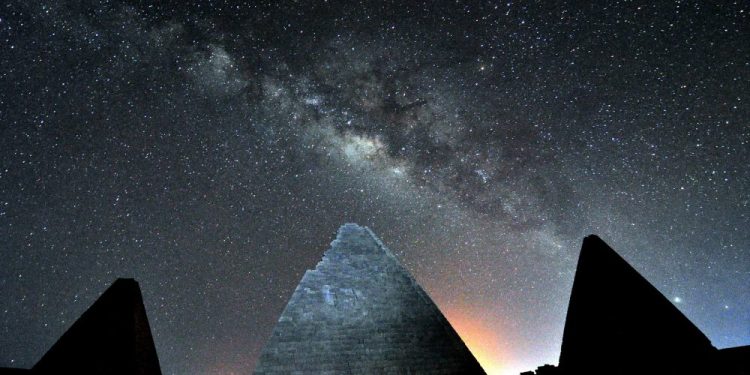

Unlike the Egyptian Pyramids, which supposedly served as tombs where the kings were ‘buried’ inside the monuments, the Pyramids of Sudan have a key difference: the tombs of the pharaohs were placed beneath the structure, instead of inside them.

It is beneath these ‘forgotten pyramids’ where a group of archeologists exploring Sudan’s hot desert has made a mind-boggling discovery.

Thousands of years ago, Nubia’s land was home to the Black Pharaohs and a collection of ancient pyramids that were equally fascinating, although not as big as the Egyptian ones.

Some of these pyramids were explored, partially at least, by archeologists several decades ago.

One of these pyramids, belonging to a ruler called Nastasen, was explored around a century ago. It was forgotten and buried by the sands again.

Exploring the Pyramid

Packed with diving gear and their must-have archeological tools, experts wanted to take a glimpse inside the tomb of the ancient Pharaoh.

But the mission was far more complicated than it sounds.

To get to the tombs, the archaeologists had to overcome several obstacles.

The biggest one was water: To access the passageways and chambers beneath the Pyramid, researchers had to dive through mud-filled water.

Luckily for them, the tomb that they were now exploring was already entered by George Reisner, a Harvard Egyptologist that had visited Nuri a century ago.

The interior of the ancient burial had briefly been excavated by Reisner and his team.

Reisner had visited Nuri, located on the west side of the Nile, discovering a burial chamber beneath the Pyramid of Taharqa, the largest of the 20 pyramids that served as tombs for the Kushite royalty.

His discovery changed how we see the Nubian Pyramids and revealed new mysteries that were waiting to be brought to the general public’s attention.

Reisner and his team also succeeded in mapping more than 80 royal Kushite burials, a quarter of which are topped by Pyramids, explained archeologist Kristin Romey, who details their journey in an article by National Geographic.

Thanks to Reisner’s work, archeologists knew that many of the burials were filled with water, making traditional archeological excavations an impossible task.

Reisner and his team excavated Nastasen’s Pyramid briefly.

According to his notes, one of his team members entered the tomb, making his way to the final chamber.

There, he managed to dig a small pit in the corner, eventually collecting small figurines, placed there to be used in the Pharao’s afterlife. The items were collected, and Reisner and his team left. The tomb was eventually forgotten briefly, as it was buried under the golden sands.

Archaeologists and National Geographic grantee Pearce Paul Creasman decided to follow Reisner’s footsteps and enter the tomb.

It was precisely in the Pyramid belonging to Nastasen. After accessing a submerged tunnel and three chambers filled with water, that underwater archeologists discovered a treasure-trove of artifacts inside the submerged tomb of a Pharaoh called Nastasen, ruler of Nubia and the Kush Kingdom from around 335 BC to 315 BC.

After making it through a staircase leading to the tomb of Nastasen, archaeologists encountered an underground water table.

To go further, they needed to put on their diving gear and work some underwater archeology.

Packed with oxygen tanks and archeological tools, they wanted to see what the tomb was like.

Led by Creasman, the team made their way into the unknown.

“There are three chambers, with these beautiful arched ceilings, about the size of a small bus, you go in one chamber into the next, it’s pitch black, you know you’re in a tomb if your flashlights aren’t on,” Creasman revealed in an interview with the BBC News. “And it starts revealing the secrets that are held within.”

“Creasman and I both trained as underwater archaeologists, so when I heard that he had a grant to explore submerged ancient tombs, I gave him a call and asked to tag along,” she wrote. “Just a few weeks before I arrived, he entered Nastasen’s tomb for the first time, swimming through the first chamber, then a second, then into a third and final room, where, beneath several feet of water, he saw what looked like a royal sarcophagus. The stone coffin appeared to be unopened and undisturbed,” revealed archeologist Kristin Romey, in an article on National Geographic.

Water levels were high and resulted from what experts described as the “rising groundwater caused by natural and human-induced climate change, intensive agriculture near the site, and the construction of modern dams along the Nile.”

Nonetheless, the scientists made their way into the tomb, eventually surfacing with fragments of gold foil that once covered figurines inside the ancient tomb.

The third and final chamber beneath the Pyramid is where experts believe the Pharaoh is buried.

Creasman and Romey acceded the chamber in their diving gear and floated just above the 2,300-year-old undisturbed sarcophagus of Nastasen.

Now, packed with experience and knowing what to expect, their aim is to return to the site in the future and attempt to excavate the burial chamber in what they themselves argue is an audacious and logistical challenge.

To learn more about the Nubian Pyramids and their priceless treasures, visit nuripyramids.org.

Join the discussion and participate in awesome giveaways in our mobile Telegram group. Join Curiosmos on Telegram Today. t.me/Curiosmos