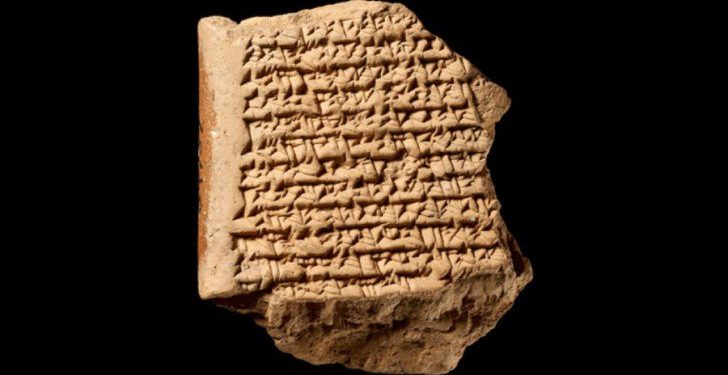

Ancient Babylonian astronomers were tracking Jupiter’s movements long before Europe invented calculus—and one clay tablet may prove it. Known today as the Babylonian map of Jupiter, this 2,000-year-old artifact shows how early sky-watchers used geometry to follow the planet’s path across the night sky.

It’s one of the most important discoveries ever made in the history of science—and most people have never heard of it.

A lost technique hiding in plain sight

For decades, scholars had studied a set of cuneiform tablets unearthed in modern-day Iraq during the 19th century. They knew these tablets held astronomical data, but one shape on a particular tablet left researchers puzzled: a trapezoid.

That mystery lingered until 2015, when historian Matthieu Ossendrijver of Humboldt University in Berlin pieced the puzzle together. After examining high-resolution photos of five Babylonian tablets stored at the British Museum, he discovered something remarkable.

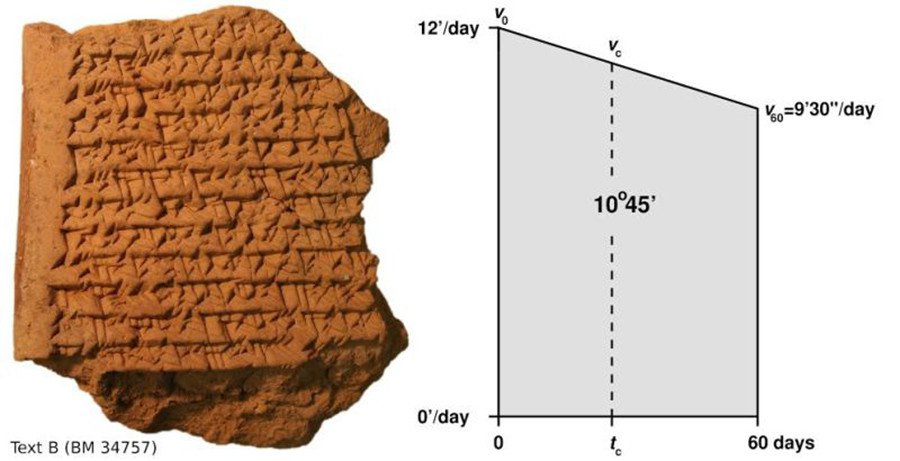

That trapezoid wasn’t decorative—it was mathematical. It allowed Babylonian astronomers to calculate the distance Jupiter traveled in the sky over a period of time. In modern terms, they were using geometry to calculate the area under a velocity-time graph—a key concept in integral calculus.

The Babylonians were doing real math

The Babylonian map of Jupiter wasn’t just an observation log—it was a working mathematical model. The astronomers divided time into intervals, measured how far Jupiter moved, and used a trapezoid to estimate the planet’s changing velocity.

They weren’t just tracking positions; they were modeling motion.

This breakthrough pushes back the timeline of abstract mathematical thinking by over a thousand years. Until this discovery, historians believed the use of geometry for such purposes began in 14th-century Europe. The Babylonians were doing it in the 2nd century BCE.

Why they tracked Jupiter so closely

In Babylonian culture, Jupiter was more than just a planet—it was linked to the god Marduk and considered a powerful omen. Its movements were thought to predict earthly events, from weather patterns to royal successions.

Understanding Jupiter’s position wasn’t academic—it was essential. It shaped beliefs about agriculture, economics, and the fate of empires.

That’s why these astronomers went beyond simple arithmetic. The techniques preserved in the Babylonian map of Jupiter were tools of influence and divination, wrapped in mathematics.

The fifth tablet that unlocked it all

Ossendrijver had been studying four Babylonian tablets for years, but something about them never quite added up. Then he came across a fifth tablet—known as BM 40054—and everything clicked. The strange trapezoid carved into the stone finally made sense. It wasn’t just a symbol; it was a working diagram used to calculate how far Jupiter had moved across the sky.

That was the missing piece. The Babylonians had figured out a way to track Jupiter’s motion using geometry—specifically, the area of a trapezoid—over 1,400 years before anything like that appeared in Europe. They weren’t just jotting down observations. They were doing real math.

The implications are huge. This single tablet pushed the history of mathematical astronomy back by over a millennium. It showed that ancient Mesopotamian scholars were far more advanced than we’ve given them credit for.

And maybe the wildest part? This breakthrough wasn’t uncovered in some new dig. It was sitting in a museum the whole time—waiting for someone to look at it with fresh eyes.