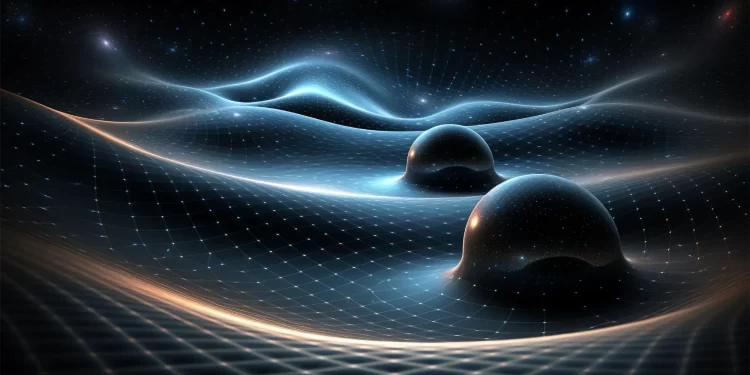

Gravitational memory may be the missing key to unlocking the hidden history of black hole mergers. Scientists have long searched for evidence that massive cosmic collisions leave a permanent imprint on spacetime. A groundbreaking new study suggests that these elusive traces could be hidden in the cosmic microwave background (CMB)—the oldest observable light in the universe.

What is Gravitational Memory?

Gravitational waves—ripples in spacetime caused by black hole mergers, supernovae, and other cataclysmic events—were first detected by LIGO in 2015. However, these waves may also leave behind a permanent shift in spacetime, known as gravitational memory. Unlike gravitational waves that pass through the universe, gravitational memory remains embedded in the fabric of space itself.

This effect is extremely difficult to detect because it is far weaker than the waves that create it. But if we can find evidence of gravitational memory, it could open an entirely new way to study black hole mergers and the evolution of the cosmos.

The Cosmic Microwave Background as a Hidden Archive

The cosmic microwave background (CMB) is the oldest radiation in the universe, dating back 13.8 billion years. It is essentially the first light ever emitted, carrying imprints of the earliest moments of the cosmos. According to a team of researchers from the Niels Bohr Institute in Denmark and the University of Valencia in Spain, this relic radiation might contain traces of gravitational memory.

As gravitational waves travel through space, they interact with photons, subtly altering their paths and wavelengths. These tiny distortions could be recorded in the CMB, providing a hidden record of every black hole merger that has ever occurred.

If this theory is correct, then analyzing temperature variations and polarization patterns in the CMB could allow scientists to reconstruct ancient cosmic events—even those that occurred billions of years ago.

Why This Discovery Would Change Astrophysics

Detecting gravitational memory would be a breakthrough in gravitational wave astronomy. Here’s why:

- It could reveal the mass, energy, and distances of ancient black hole mergers.

- It may help scientists refine models of cosmic evolution.

- It could provide insights into early-universe phenomena beyond what telescopes can detect.

Unlike traditional gravitational wave detectors, which rely on current mergers, the CMB may hold a historical record of collisions spanning billions of years.

The biggest obstacle to confirming gravitational memory is its weak signal strength. Even the most advanced observatories, such as LIGO and Virgo, have been unable to detect it. The next generation of gravitational wave observatories—including NASA’s Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA)—might finally have the sensitivity needed to uncover these cosmic imprints.

As the researchers put it, “The entire merger history of black holes is written in the cosmic microwave background, waiting to be discovered.” If this theory holds, then studying gravitational memory could revolutionize our understanding of black holes and the structure of the universe.