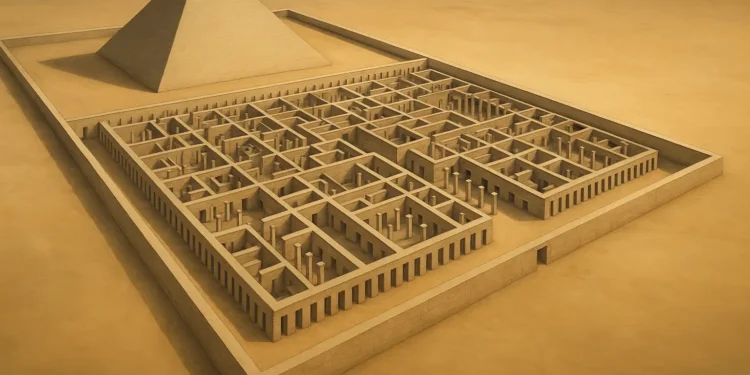

Herodotus described an Egyptian labyrinth so extraordinary that he claimed it surpassed even the pyramids in complexity and grandeur. Said to contain thousands of rooms, marble-covered halls, and a hidden pyramid, the labyrinth was once a wonder of the ancient world—yet today, no fully intact structure matching his account has ever been found.

A forgotten wonder recorded by the father of history

Herodotus, often called the “father of history,” journeyed to Egypt in the 5th century BCE and wrote extensively about its monuments, customs, and mysteries. Among his most fascinating accounts is a description of a colossal labyrinth located near the Faiyum Oasis, not far from the Nile. His depiction was detailed and specific—far from hearsay.

In Histories Book II, he wrote:

“There I saw twelve palaces regularly disposed, which had communication with each other, interspersed with terraces and arranged around twelve halls. It is hard to believe they are the work of man. The walls are covered with carved figures, and each court is exquisitely built of white marble and surrounded by a colonnade… Near the corner where the labyrinth ends, there is a pyramid, two hundred and forty feet in height, with great carved figures of animals on it and an underground passage by which it can be entered.”

Herodotus described a staggering 3,000 rooms—half above ground, half below—guarded and inaccessible to ordinary people. His awe was clear. He wrote that even the pyramids did not surpass the grandeur of the labyrinth.

Herodotus wasn’t the only witness

Other ancient writers confirmed seeing—or at least knowing about—this labyrinth. The geographer Strabo, writing in the 1st century BCE, also mentioned it, noting that it was partly ruined in his time but still impressive. Diodorus Siculus and Pliny the Elder also referenced the structure in their works.

Strabo wrote:

“They made a building, a work beyond description… It is hard to believe that it is the work of men.”

This suggests the labyrinth was not only real but remained at least partially visible centuries after it was built.

Where was this Egyptian labyrinth?

Most researchers associate Herodotus’s labyrinth with the ruins at Hawara, near the pyramid of Amenemhat III, a pharaoh of Egypt’s 12th Dynasty (circa 1850 BCE). In the 1880s, famed archaeologist Flinders Petrie excavated the site and confirmed that an enormous structure once stood there. He found stone foundations and walls indicating a large, complex layout—likely the remains of the labyrinth Herodotus described.

However, what Petrie uncovered was only the base. The superstructure described by Herodotus, with white marble colonnades and intricate carvings, had been dismantled over the centuries, its stones reused for other buildings. Still, the size and location matched the ancient descriptions closely.

A pyramid with hidden connections?

One of the most mysterious parts of Herodotus’s account is his claim that a pyramid stood at the end of the labyrinth—one that could be entered through an underground passage. He even relayed reports that the subterranean chambers were connected to the pyramids of Memphis.

Modern archaeology has not verified such connections. No tunnels have been found linking the site at Hawara to any pyramids in Memphis, which is about 100 kilometers north. It’s possible that Herodotus was either repeating local legends or misinterpreting complex architecture. Still, the pyramid described near the labyrinth likely corresponds to the pyramid of Amenemhat III, which still stands today, though weathered and partially collapsed.

What did the labyrinth contain?

Herodotus noted that only priests were allowed into the underground chambers, and he was not permitted to enter them himself. He did not describe their exact contents, but the fact that they were sealed and inaccessible implies they may have held something of importance—perhaps royal tombs, religious records, or sacred texts.

Other writers claimed that the labyrinth housed documents from Egypt’s earliest dynasties and possibly even predynastic times. However, no inscriptions or papyri have ever been recovered from the site to confirm such claims.

What is known is that the labyrinth likely served multiple functions—religious, ceremonial, and administrative. Given its proximity to the pyramid of Amenemhat III, it may have formed part of a broader funerary complex.

The decline of the labyrinth was likely gradual. Natural erosion, looting, and centuries of stone quarrying likely erased the structure above ground. By the time of Strabo, it was already in ruins. Today, the ruins at Hawara are still visible, but only traces of the once-great labyrinth remain.

Even so, Herodotus’s vivid account and the corroboration by later writers suggest that it truly existed. The Egyptian labyrinth of Herodotus might not have vanished entirely—but much of it remains buried, waiting for a new generation of archaeologists to uncover more.