We wake up to buzzing alarms, track our days with smartphone calendars, and count every second with atomic precision. But none of this would exist without a much older story — one written not in code or paper, but in the sky.

How did prehistoric people track time and eternity?

Long before clocks or calendars, prehistoric people tracked time in ways we’re only beginning to understand. They followed the Moon through its phases, watched the Sun carve paths across the seasons, and marked time with stones that still stand thousands of years later.

They didn’t measure time. They lived inside it.

From shadow-casting pillars in the desert to spirals carved deep in cave walls, the prehistoric people left behind more than just artifacts — they left clues to a cosmic awareness that modern science still struggles to explain.

Reading the Sky How the Sun and Moon Taught Time

Before there were cities, even before farming took root, there was the sky. The Moon, with its reliable cycle of waxing and waning, offered early people a natural clock. A full lunar cycle lasts about 29.5 days — close to a modern month — and this rhythm shaped everything from travel to hunting, even menstruation and mythology. Lunar calendars were used by early hunter-gatherers and persisted for millennia. In fact, some of the oldest known markings on bones — like the 20,000-year-old notches found on the Ishango bone in Central Africa — appear to track the phases of the Moon.

But the Sun offered a second layer of time: the year. Ancient observers noticed that it rose and set at slightly different points along the horizon each day, reaching extremes at the solstices and balancing out during the equinoxes. Across the world, people placed markers — standing stones, passage graves, carved lines — to capture these solar moments. Sites like Newgrange in Ireland (built around 3200 BCE) are aligned so precisely that on the winter solstice, the rising sun pierces a dark passage and illuminates the burial chamber within.

These were not random alignments. They were calendars in stone.

Stone Shadows and the Birth of the Sundial

Some of the earliest timekeeping wasn’t about years — it was about hours.

A vertical stick planted in the ground casts a shadow, and that shadow moves predictably with the Sun. This is the basis of the gnomon, the ancestor of the sundial. Ancient builders used this simple principle to track daily time long before the invention of mechanical clocks.

But these were more than tools — they were symbols of order. In ancient Egypt, obelisks rose from temple courtyards not only as monuments, but as solar markers. Their shadows crawled across carefully designed pavements, dividing the day into parts and signaling times for prayer, ritual, or rest.

Even older evidence comes from Nabta Playa, a stone circle in Egypt’s Nubian Desert. Dating back to at least 6,000 BCE, it features alignments with stars and possibly the summer solstice — making it one of the world’s oldest known astronomical sites. In the Andes of Peru, Chankillo — a mysterious site with thirteen stone towers on a ridge — served as an ancient solar observatory around 300 BCE. As the Sun rose along the horizon throughout the year, it would appear between different towers, effectively turning the landscape into a living calendar.

These systems weren’t crude or mystical. They were observational science rooted in landscape, light, and memory.

Cosmic Cycles and the 25000-Year Clock

Most of us are familiar with the day, the month, and the year. But there are even deeper cycles — ones that take tens of thousands of years to unfold.

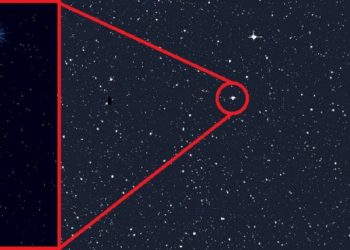

One of these is the precession of the equinoxes, a slow wobble in Earth’s rotation that shifts the position of the celestial equator. Over roughly 25,800 years, the stars we see at night gradually change position, subtly altering the backdrop of the heavens.

This concept wasn’t officially understood by science until the second century BCE. But some researchers believe that prehistoric people and ancient cultures were aware of it — not through telescopes, but through myth. The Sphinx in Egypt may have once faced the constellation Leo at sunrise during the spring equinox around 10,500 BCE — a date that aligns with the supposed beginning of a “Great Year” in some ancient belief systems.

The idea of “ages” defined by star positions appears in Babylonian texts, Vedic scriptures, and Greek philosophy. In India, Yuga cycles span hundreds of thousands of years. In Mesoamerica, the Long Count calendar tracks time in cosmic phases, with one cycle lasting over 5,000 years. Even the concept of zodiac ages — like the shift from Pisces to Aquarius — hints at an ancient understanding of long-term celestial movement. And these patterns weren’t just for record-keeping. They were tied to prophecies, world renewals, and cosmic resets. Time wasn’t a line. It was a wheel.

Myth Memory and the Shape of Time

The way we experience time — linear, relentless, forward-moving — is a relatively modern idea.

Many prehistoric people saw time not as a race toward the future, but as a recurring loop. Events repeated. Ages returned. Heroes were reborn.

The Mayans believed history moved through great cycles, each ending with transformation or collapse. The Hindu yugas represent a moral arc: from golden beginnings to dark decline, only to begin again. And in Greek philosophy, the concept of the “eternal return” suggested that everything that has happened will eventually happen again.

Even spirals, found carved into rock across the world — from Irish tombs to American petroglyphs — may represent this idea. Unlike a circle, a spiral moves forward but repeats its shape — a perfect symbol for time that loops but never stands still.

To these cultures, memory wasn’t just about the past. It was a map of what’s to come.

What We Inherited and What We Lost

If prehistoric people once measured time by stars and spirals, it’s worth asking what we’ve gained with modern clocks — and what we may have left behind.

Today, time is exact. We break it down to the second, sync it across devices, and plan our lives around schedules. But in doing so, we’ve drifted from the older rhythms — sunrise and sunset, the turning of the seasons, the quiet pull of the moon.

Our ancestors didn’t need digital reminders. They followed the sky. They remembered patterns passed down through generations. A shadow cast at noon. A full moon rising. A stone lighting up only once a year.

Next time you step outside at night, look up. The same stars they watched are still turning overhead. And maybe they were never just keeping time — they were living inside it.