When we think of pyramids, most minds jump to Egypt. But the pyramids in North America tell a different story—one of forgotten civilizations, lost building traditions, and ancient ingenuity that has often been overlooked. From shell-built mounds in Brazil to massive structures in Mexico, these sites reveal a much broader history of pyramid-building than what we learn in school.

Why the real pyramid capital might not be where you think

Egypt may have the fame, but it doesn’t have the numbers. While the Giza plateau is home to some of the most iconic pyramids in the world, Africa hosts about 350 known pyramid structures, most of them in Egypt and Sudan. In contrast, when we tally up the pyramids in North America—including those across the U.S., Mexico, and even further south—the total exceeds 2,000. And that’s a conservative estimate.

Many of these pyramids look different from what most people expect. Some are made of earth or seashells, not stone. Some are hidden under hills or mistaken for natural mounds. Others served entirely different purposes—calendars, temples, burial sites—depending on the culture that built them.

Yet across all these regions, a shared architectural idea emerged: building monumental structures with a distinctly pyramidal shape. Whether they were built independently or influenced by earlier traditions remains debated, but the scale and frequency of these pyramids prove they were central to ancient American societies.

The earliest pyramids arent where you think they are

I know that this article is about pyramids in North America, but I feel like I have to mention thins in the article since it is kind of important. Long before the Maya or Egyptians raised their massive stone pyramids, ancient builders along the Brazilian coastline were shaping huge mounds entirely out of seashells.

These now-lost pyramids, built more than 5,000 years ago, may be the oldest known pyramids on Earth—predating Egypt’s Step Pyramid of Djoser by roughly 300 years. Archaeologists have identified hundreds of such structures, many now destroyed, that once dotted the Atlantic coast of Brazil.

These weren’t random shell heaps. The mounds were carefully constructed and in some cases reached more than 30 meters in height. They often included burials, ceremonial features, and signs of long-term habitation. Researchers believe the builders were early fishing communities who viewed these mounds as both sacred and functional spaces.

Unfortunately, by the 19th and 20th centuries, many of these structures were misidentified as trash piles or natural hills and bulldozed for livestock pastures, roads, or settlements. As a result, an entire chapter of early American architecture was almost completely erased. Even more interesting, LiDAR scans have now revealed that there are many remnants of vast major ancient cities hidden deep beneath the Brazilian rainforest. And I would not be surprised if future explorations with new technologies revealed more pyramids.

Independent pyramid-building or shared origins?

According to conventional chronology, the Step Pyramid of Djoser in Egypt was built around 4,700 years ago and is considered the first monumental stone pyramid. But the Brazilian shell pyramids are dated to around 5,000 years ago, and the Caral pyramids in Peru emerged around the same time as Djoser’s—raising important questions.

Did pyramid-building arise independently in multiple regions, or was there an earlier, now-lost cultural connection across continents?

Most mainstream scholars support independent development, arguing that similar shapes arise from similar needs: large, stable platforms for religious or political use. In Egypt, pyramids evolved from mastabas—flat-roofed tombs. In America, they often evolved from platform mounds, used for ritual or communal activities.

In both cases, the pyramid form appears around the same time globally, in the “blink of an eye” in historical terms. That sudden appearance has prompted ongoing debate.

In Mexico, pyramids reached unprecedented scale

Among the most impressive pyramids in North America is the Great Pyramid of Cholula in modern-day Mexico. Though less known than Giza, it is in fact the largest pyramid on Earth by volume, measuring over 4.45 million cubic meters—nearly double that of the Great Pyramid of Giza, which contains about 2.5 million cubic meters.

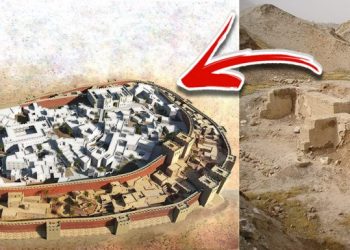

Cholula was once a bustling pre-Columbian city of over 100,000 people. Its central pyramid grew over centuries as temples were repeatedly built atop older ones, creating a layered superstructure. Today, the pyramid is mostly buried beneath a hill—so well concealed that when the Spanish conquistadors arrived, they failed to recognize it as a man-made structure.

According to one legend, the local population deliberately covered the pyramid to protect it from destruction. Whether by design or nature, it worked. The Spanish built a church, Nuestra Señora de los Remedios, on top of the mound. That church still stands today.

Beneath it, archaeologists have uncovered a vast network of tunnels and chambers that reveal the true scale of the ancient temple. Cholula was a religious and political center, and its pyramid may have served as a calendar, ceremonial platform, and sacred mountain all in one.

El Tajín and the Pyramid of Niches: an ancient calendar in stone

Another remarkable site lies in Veracruz, Mexico, at El Tajín, a city that peaked around the 8th century CE. Its most famous structure, the Pyramid of Niches, is a stone step pyramid with an extraordinary feature: 365 carved niches, each exactly 60 centimeters deep.

The precision suggests these niches may represent days in the solar year, functioning as a monumental calendar. The pyramid’s design is not just aesthetic—it carries astronomical and symbolic meaning, reflecting how closely the builders tracked celestial patterns.

The Pyramid of Niches is a stunning example of how ancient American civilizations embedded science, religion, and architecture into a unified structure.

Comalcalco: the Maya pyramid built from bricks

In Tabasco, Mexico, the Maya city of Comalcalco breaks from all expectations. Unlike other Maya sites built from limestone, Comalcalco’s central pyramid was constructed using fired clay bricks and mortar.

Many of these bricks are marked with unusual symbols. Some researchers have compared them to Roman characters, sparking fringe theories of transatlantic contact. While no direct link to Rome has ever been proven, the brickwork itself is exceptional.

It remains the only known brick-built Maya pyramid, showing that even within a single civilization, regional variations and experimentation occurred. Comalcalco reminds us that ancient builders weren’t simply copying a template—they were innovating constantly.

Why we don’t hear about these pyramids

Despite the clear archaeological significance of these structures, they remain underrepresented in mainstream history education. Part of the issue is material bias—pyramids made of stone survive better than those built from shells, clay, or earth. But it’s also about cultural visibility. Egyptian monuments were publicized early through European exploration, while many American sites were misidentified, looted, or buried. But what I find most amazing is the fact remains: pyramid-building was a global phenomenon, and North and South America were central to that story.

From the 5,000-year-old Brazilian mounds to the brick temples of Comalcalco, these forgotten monuments show that human ingenuity—and our desire to reach upward—transcended geography.