The origin of human mtDNA is a subject that continues to raise big questions about how — and when — modern humans truly began.

It might sound like the start of a myth or a sci-fi theory — but according to a widely discussed genetic study, there’s a surprising possibility that all human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) can be traced back to a single population that lived around 200,000 years ago. This idea doesn’t mean humans came from just two individuals. Instead, it highlights a fascinating pattern in our genetic history — one that might reshape how we think about our origins.

Exploring the origin of human mtDNA through ancient genetics

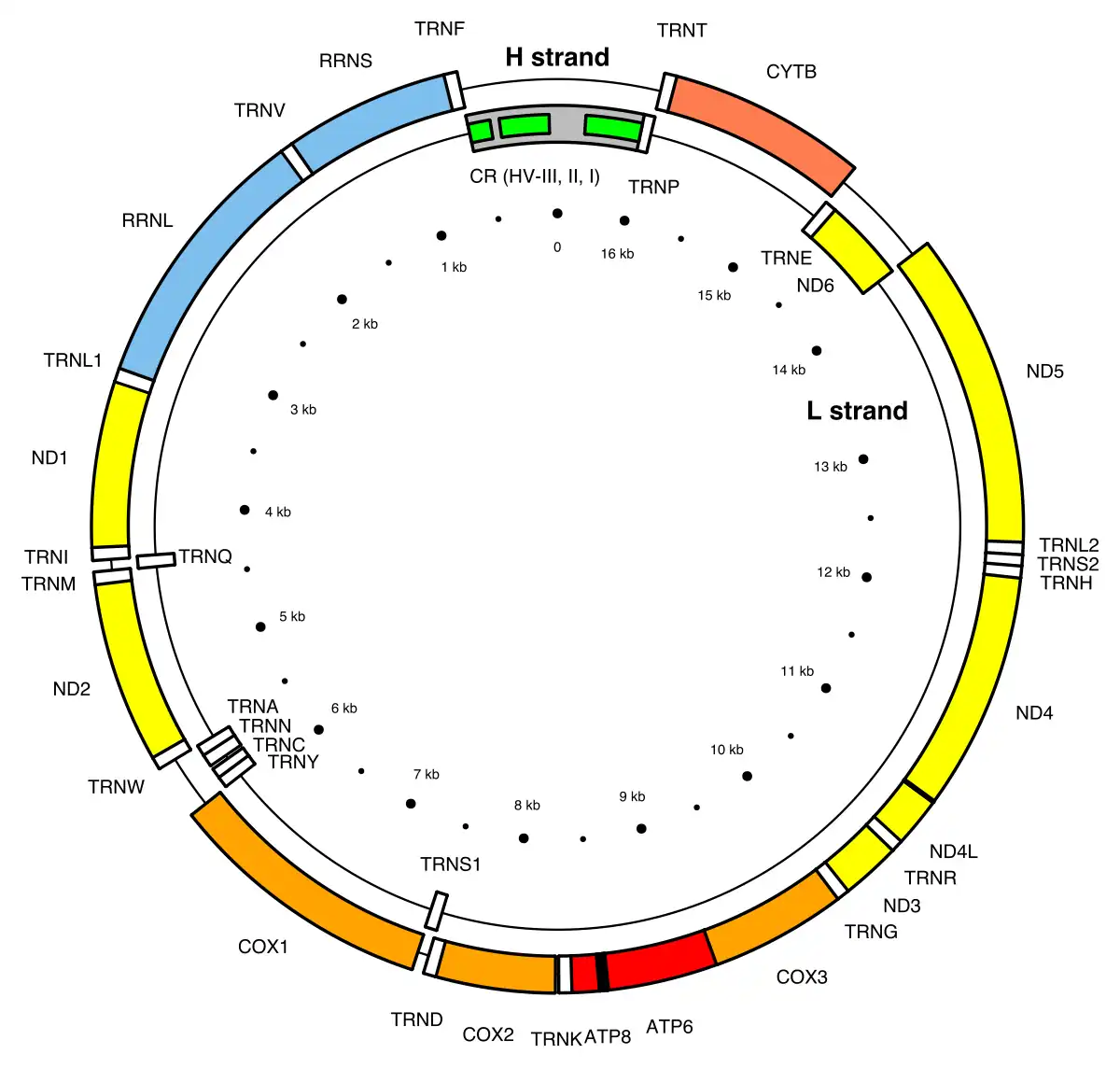

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is a unique part of our genome. Unlike nuclear DNA, which comes from both parents, mtDNA is passed down exclusively through mothers, unchanged except for small mutations over time. This makes it incredibly useful for tracing direct maternal ancestry through thousands of generations.

In 2018, researchers from Rockefeller University and the University of Basel analyzed mtDNA from over 5 million specimens representing more than 100,000 species, including modern humans. Their results were surprising: the vast majority of species, humans included, showed remarkably low genetic variation in their mitochondrial DNA — as if they all originated from a small founding population.

A genetic bottleneck of human mtDNA?

The researchers proposed that at some point between 100,000 and 200,000 years ago, humanity experienced a population bottleneck — a time when the human population was reduced to relatively few individuals. Whether this was due to a catastrophic environmental event, disease, or something else entirely is still debated.

What matters is that this group — possibly in the thousands, not just two people — became the source of all modern human mitochondrial lines. Over time, the mtDNA from other lineages may have simply faded out through natural population dynamics, leaving only the surviving line.

Other species show similar patterns

One of the most surprising parts of the study was that over 90% of animal species seem to have experienced a similar mitochondrial reset. Birds, fish, insects — all appear to trace their mtDNA back to a founding population that lived within the last 200,000 years.

This suggests that periodic resets may be a recurring pattern in evolutionary history — triggered by ice ages, volcanic eruptions, or other large-scale changes that temporarily reduce genetic diversity.

Does this mean we’re all descended from a “mitochondrial Eve”?

Kind of — but not in the way it might sound. Scientists sometimes refer to the most recent common ancestor of modern human mtDNA as “mitochondrial Eve”, but she wasn’t the only woman alive at the time. Her mtDNA lineage is simply the one that survived to the present day. Think of it like this: in a huge ancestral family tree, many branches eventually stop — through no fault of their own. The ones that remain become the basis for future generations. Mitochondrial Eve wasn’t the first woman, or the only one — just the one whose maternal line never ended.

What does this tell us about human history?

The study’s authors — Mark Stoeckle and David Thaler — were the first to admit how surprising the results were. Thaler even said, “I fought against it as hard as I could.” But after double-checking the data, the findings held up.

Their work doesn’t prove a literal “Adam and Eve” scenario, but it does support the idea that our species went through a period of near-collapse, leaving us genetically more similar than we might expect.

And while nuclear DNA tells a much more complex story involving interbreeding populations across Africa and beyond, mtDNA offers a zoomed-in lens on one piece of that story — the maternal one.

So… what really happened 200,000 years ago?

That’s the question researchers are still working on.

It could have been a volcanic winter, a rapid climate shift, or some unknown evolutionary bottleneck. Whatever it was, the mitochondrial legacy of that event still lives in each of us today.

Studies like this highlight how evolution doesn’t always follow a straight line. Behind the differences we see today, there may be shared moments of survival that connect us — not just as people, but as part of a much broader story of life on Earth.