The most detailed view yet of the universe’s earliest light has just been revealed—offering a rare look at the moment the cosmos began to take shape. Captured by a global team of scientists using the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) in Chile, this new dataset brings us closer to understanding how the first stars and galaxies formed, and what they can tell us about how fast the universe is truly expanding.

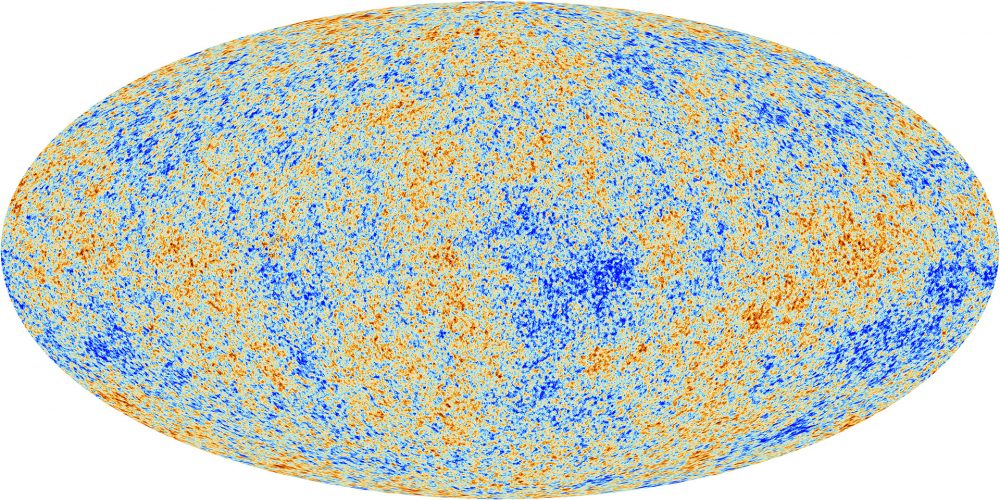

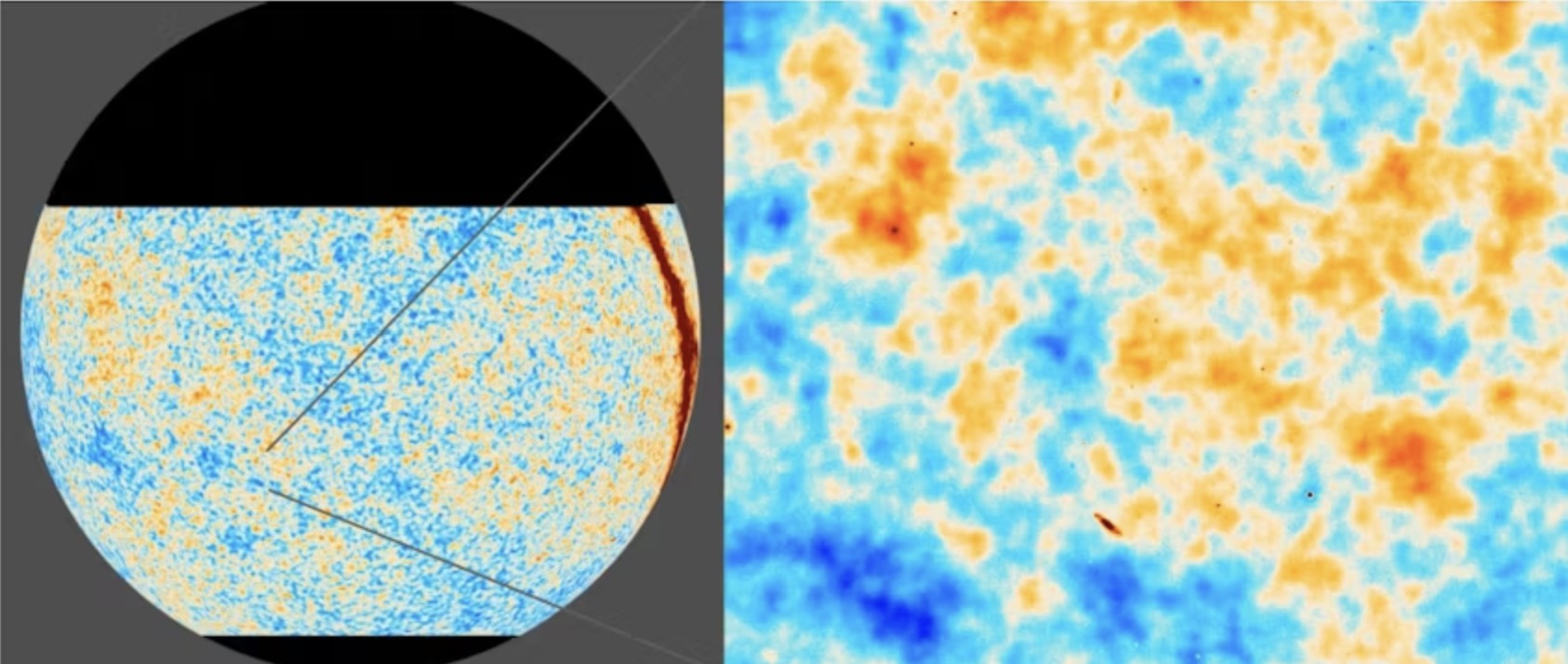

By measuring the faint traces of the cosmic microwave background—light that’s traveled more than 13 billion years to reach us—researchers have reconstructed the state of the universe when it was just 380,000 years old. These new images go beyond previous efforts in both precision and depth, offering a critical benchmark in a field where every detail counts.

But this breakthrough isn’t just about looking backward—it’s also about resolving a tension that’s been growing louder in the world of cosmology: how fast is our universe expanding, really?

A universe written in light

What these new images show is nothing short of extraordinary. The data reveals early clouds of hydrogen and helium collapsing under gravity—structures that would later evolve into the very first galaxies.

Key findings include:

-

The observable universe stretches almost 50 billion light-years in every direction

-

Its mass equals nearly 1,900 zetta-suns—roughly 2 trillion trillion times the mass of our Sun

-

Only 100 zetta-suns represent “normal matter”—hydrogen, helium, and the elements we’re made of

-

The rest is split between dark matter (500 zetta-suns) and dark energy (1,300 zetta-suns)

Credit: ACT Collaboration; ESA/Planck Collaboration.

Professor Erminia Calabrese, who led the analysis, explained that this level of precision allows us to “trace the seeds of all cosmic structure,” from galaxy clusters to the atoms in our own bodies.

The battle over the Hubble constant just got hotter

At the heart of modern cosmology lies one of its most uncomfortable problems—the Hubble tension. That’s the name scientists have given to the growing disagreement between two different ways of measuring the expansion rate of the universe.

One method, using nearby galaxies, suggests the universe is expanding at around 74 km/s/Mpc. But measurements from the cosmic microwave background give a lower rate—around 67 km/s/Mpc.

This new data from ACT backs the lower value, and with more precision than ever before. According to Calabrese, the team examined dozens of alternate models that might explain a faster expansion, but “none of them fit the data.”

The implication? Some of the most radical theories trying to explain this discrepancy may now be off the table.

This marks the final release of ACT’s data after nearly two decades of operation. Since 2004, it has played a central role in shaping our picture of the early universe. Now, attention is shifting to the Simons Observatory, a next-generation facility set to continue this work with even greater resolution.

For researcher Hidde Jense, who worked on the final phase of ACT’s data analysis, the project represents the culmination of years of effort. “ACT has been my cosmic laboratory during my Ph.D. studies. It has been thrilling to be part of the endeavor leading to this refined understanding of our universe,” he reflected.