About 74,000 years ago, a vanished supervolcano in what is now Sumatra erupted with such force that it left a mark on the entire planet. The explosion created a massive crater that would later become Lake Toba, but its impact reached far beyond the island. Ash fell across continents. Skies dimmed. Global temperatures dropped. For early humans, it may have been a moment of crisis unlike any before.

The Toba eruption left no towering cone behind. Instead, the collapsed caldera filled with water, masking the scars of disaster beneath a tranquil lake. But scientists have spent decades uncovering what happened, and the more they learn, the more it becomes clear that this vanished supervolcano may have permanently altered the course of human history.

A blast beyond comprehension and a vanished supervolcano

The eruption of Toba was not an ordinary geological event. It was a supereruption, releasing up to 2,800 cubic kilometers of volcanic material into the atmosphere. That’s nearly three thousand times more than the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens and over a hundred times greater than Krakatoa in 1883.

Ash from Toba has been found in deposits as far away as southern Africa and the Indian Ocean, signaling how far the eruption’s effects stretched. For weeks, the skies in many parts of the world would have been dimmed, the Sun obscured by a global veil of sulfuric aerosols and volcanic dust. Temperatures plummeted. Rainfall patterns shifted. The ecosystems that had nurtured early human communities began to break down.

While the Toba caldera today may appear serene, the force that created it was not. What I find most mind-boggling is that the eruption emptied a massive magma chamber, causing the overlying land to collapse inward and form a crater roughly 100 kilometers long and 30 kilometers wide, one of the largest of its kind anywhere in the world.

Near-extinction or survival bottleneck?

One of the most striking ideas linked to the Toba eruption is the hypothesis that it nearly wiped out early Homo sapiens. Genetic studies have revealed a sharp reduction in human genetic diversity around the same time, suggesting that our ancestors may have passed through what scientists call a population bottleneck.

Some researchers propose that the number of humans alive after Toba’s eruption may have dropped to fewer than 10,000. If true, it would mean that every person alive today descends from a small, isolated group that survived a global catastrophe. This hypothesis has been the subject of debate, but the timing between the eruption and the drop in genetic diversity remains provocative.

The survivors, scattered across Africa and parts of Asia, may have faced not only harsh climates but also disappearing food sources. Plants failed to grow, animals migrated or died off, and entire ecosystems were thrown into chaos. Adaptability, innovation, and social cooperation would have been key to survival.

Evidence buried in ash

Understanding what happened during the Toba eruption has required a multidisciplinary approach, combining geology, archaeology, climatology, and genetics. Layers of volcanic ash found in India, Malaysia, and even East Africa match the chemical signature of Toba, giving us a timeline for how and where the eruption spread.

In India’s Jurreru Valley, for example, archaeologists have found Middle Paleolithic tools both below and above the Toba ash layer. This is really interesting. The tools suggest that early human populations in the region survived the eruption, continuing to make and use stone tools in the immediate aftermath.

This discovery, among others, complicates the extinction theory. While some groups may have been wiped out, others may have survived. Climate models now suggest that the impact of the eruption, though severe, may not have been uniformly catastrophic across the entire planet. Some regions may have escaped the worst of the cooling or found ways to adapt.

Climate shock and cultural evolution

Scientists believe that the environmental shock triggered by Toba may have done more than prune the branches of humanity’s family tree. It might also have forced a leap in human innovation. Facing new challenges, early humans may have begun to develop more complex tools, social structures, and survival strategies.

Evidence from sites in South Africa shows bursts of symbolic behavior and technological advancement dating to around the time of the eruption. Ochre processing, engraved tools, and more refined hunting techniques suggest a cognitive shift, one possibly accelerated by the pressure to adapt.

Though it is difficult to draw direct lines between volcanic ash and cultural breakthroughs, the possibility remains that Toba’s eruption acted as a kind of kickstart for early human creativity. When the environment turned hostile, survival may have depended not just on physical endurance, but on imagination and cooperation.

A warning from the past

Toba wasn’t the first supervolcano, and it won’t be the last. Others are still out there. Yellowstone in the United States, Taupō in New Zealand, and Campi Flegrei in Italy are all closely watched by geologists. Some researchers say Yellowstone is overdue. With any luck, it won’t erupt in our lifetime.

What happened at Toba shows just how unstable the surface of our world can be. The early humans who lived through it weren’t prepared. They didn’t have tools to predict it or systems to protect themselves. Still, some of them managed to survive in a world that suddenly turned cold, dark, and unpredictable.

We live differently now. We have warning systems, global communication, and disaster plans. But we also depend on a fragile web of infrastructure that can fall apart quickly. A supereruption today would stop flights, disrupt food supply chains, and hit economies hard. Even with all our technology, there’s very little we could do to stop the fallout.

The lake that hides the memory

Today, Lake Toba looks calm. The water stretches wide across northern Sumatra. Villages dot the shoreline. Boats drift quietly across the surface. Most people who visit don’t know they’re standing in the middle of a collapsed volcano.

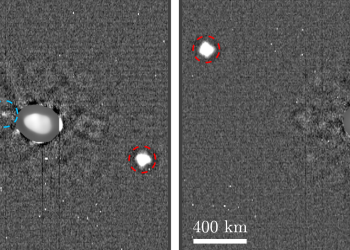

But the land remembers. Beneath the lakebed, layers of ash and sediment still carry the evidence of what happened. Scientists have been drilling into the bottom of the lake to study those layers. Each core reveals how the planet changed in the days, months, and years after the eruption. They’re learning how far the ash spread, how much the temperature dropped, and how long it took for things to recover.

The Toba eruption didn’t just shape the landscape. It may have shaped us. It forced our ancestors to adapt, to move, to survive. And even now, it’s helping us understand how humans respond when the world turns against them.

What happened 74,000 years ago isn’t lost. It’s still there, buried in the earth, waiting to be read by those who know how to look.