Before the world ticked to the rhythm of quartz watches and digital clocks, humanity looked up—to the sky, to the shadows, to the subtle flow of water—for answers. Across continents and centuries, people tracked time with tools so clever, so precise, that some still puzzle modern researchers. But more importantly, these ancient timekeeping methods weren’t just survival strategies. They were windows into how early civilizations understood the world, aligned their lives with nature, and created patterns that governed everything from harvests to holy days. What’s astonishing is how much they accomplished—without ever knowing what a “minute” was. In this article, I will go through a series of methods used by our ancestors over millennia.

The Shadow That Told the Day

Long before sundials had hour lines or decorative faces, there was the gnomon—literllay a simple stick in the ground. As the Sun moved, the shadow shifted. It sounds primitive, but it was revolutionary. In ancient Egypt, obelisks functioned as massive gnomons, casting shadows that could mark solstices and equinoxes with remarkable accuracy. In China, similar methods were used to define entire calendars. What seemed like a basic trick of light was, in fact, an early solar observatory.

The geometry was deliberate. Placement mattered. The length of a shadow at noon could determine the season, forecast weather patterns, or trigger a festival. These weren’t mere guesswork tools. These objects were precise instruments built on generations of sky-watching. After all, humankind has looked at the stars since the very beginning.

Time That Dripped, Not Ticked

When sunlight failed, water stepped in. The clepsydra, aka water clock, first appeared in Mesopotamia over 3,000 years ago. It was nothing more than a bowl with a hole—but what flowed out was structured time. In courts, water clocks limited the length of legal arguments. In temples, they timed rituals with rhythmic flow. Some were calibrated to adjust for seasonal changes in daylight—a level of complexity that modern scholars still admire.

Unlike sundials, water clocks worked in the dark. That made them crucial in night-time astronomy and religious ceremonies. They were also portable, used on ships or during long journeys when precision was still expected.

The Star That Heralded a Flood

In ancient Egypt, the annual heliacal rising of Sirius—its first appearance just before dawn after a period of invisibility—was more than a celestial event. It signaled the imminent flooding of the Nile, a life-giving phenomenon that replenished the soil and marked the beginning of the Egyptian New Year. The Egyptians associated Sirius with the goddess Sopdet (later identified with the Greek Isis), and they tracked its reappearance with meticulous care. This rising usually occurred in mid-July and became the cornerstone for their civil calendar, which was remarkably consistent and closely aligned with solar and agricultural cycles.

What’s especially impressive is that this wasn’t mere stargazing—it was predictive astronomy. It required centuries of detailed observation, pattern recognition, and recordkeeping. While ancient Europe remained largely pre-literate, Egyptian astronomer-priests were already developing a mathematical model of the sky to anticipate seasonal events critical to survival.

Moonlight as a Map

Lunar calendars were widespread, especially among cultures that depended on seasonal planting and migration. The Moon offered a reliable rhythm: new, waxing, full, waning.

What’s fascinating is how similar moon-based timekeeping systems appeared independently across the world—from Babylon and the Indus Valley to the Maya and the Inuit. In some cultures, each moon phase came with a name and a purpose. A “Planting Moon.” A “Fishing Moon.” A “Bone Moon,” when resources ran low.

They weren’t just poetic traditions. Watching the Moon helped people know when to fish, when animals would move, and when the land was ready for planting—knowledge passed down because it worked.

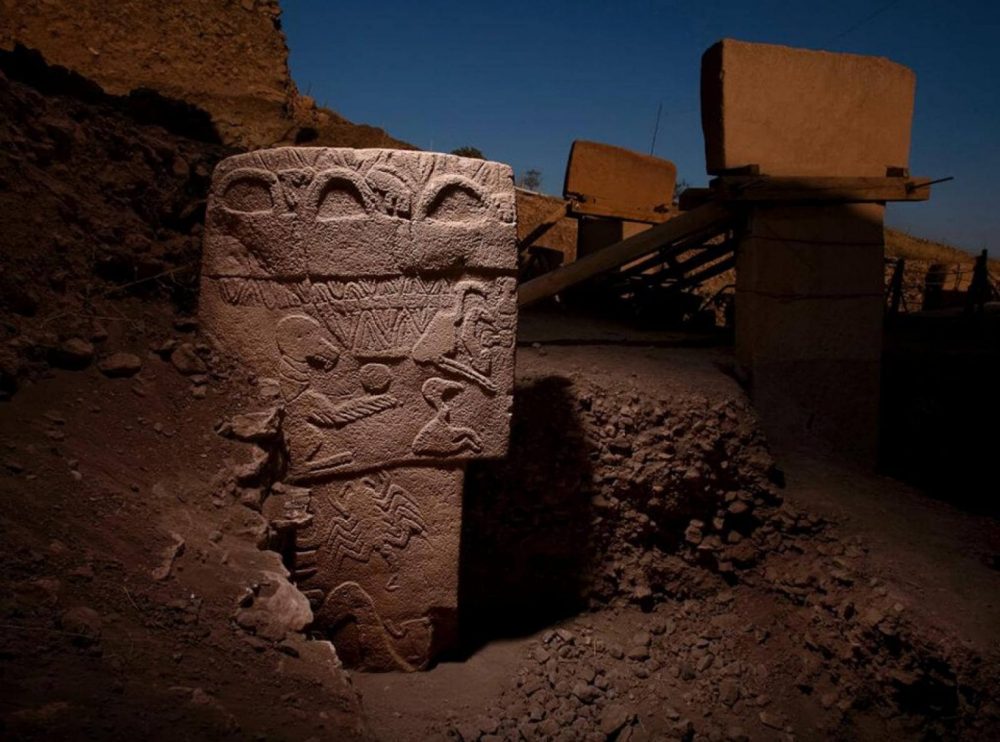

Calendars Carved in Stone

One of the most haunting examples of ancient timekeeping comes not from architecture—but from art. At Lascaux, the famed cave complex in southern France, researchers believe clusters of dots found near animal paintings may represent lunar calendars. Each dot could mark a phase of the Moon—suggesting these Paleolithic artists were also astronomers. This isn’t an isolated case. In Scotland, the Warren Field site includes a series of pits aligned with lunar cycles—dating back nearly 10,000 years. Also theres’s the Cochno stone (you can read more about it here). In the Americas, petroglyphs and rock carvings show spiral patterns and solar alignments, often tied to solstices.

What’s striking is that none of these cultures had writing systems. Yet they recorded time—with precision, with memory, and with purpose.

What Modern Scientists Still Can’t Explain

Despite our GPS satellites and atomic clocks, we still don’t fully understand how some ancient systems were calibrated with such accuracy. How did early Mesopotamians account for leap months? How did Polynesian navigators use star maps to track not just space—but time?

What we do know is this: ancient timekeeping methods were not primitive. They were adaptive, refined, and deeply connected to nature’s rhythms. In many ways, they were more holistic than modern systems—less about the exact second, and more about the right moment.

These days, we check the time on screens and race from one task to the next. But for most of human history, time wasn’t something you checked—it was something you felt. People watched shadows stretch, water drip, and stars return, not because they had somewhere to be, but because that’s how they stayed connected to the world around them.