The pyramid building fever is thought to have begun in Egypt during the Third Dynasty reign of Djoser. He is believed to have ruled over the land of Egypt from around ca. 2686 BC – 2648 BC. Depending on what sources we look at, he reigned anywhere between 19 and 28 years.

Although many Pharaohs existed before him, his reign left a profound mark in the history of Egypt; he is thought to have commissioned the very first Pyramid in Egypt, the Step Pyramid at Saqqara.

The project was led by his royal Vizier and architect Imhotep, a young man eager to prove himself in the Pharaoh’s eyes. Imhotep did not disappoint.

Basing his new design on the ancient mastaba, Imhotep would go on to produce the first step pyramid, which eventually resulted in an entirely new monument.

Egyptologists believe that Imhotep’s design draws ideas from several precedents, the most important of which c is a mastaba built at Saqqara around 2,700 BC. This ancient monument, whose substructure was built into a deep rectangular pit, was erected with walls rising 6 meters into the air. Three of the sides of the monument were extended and were built, creating an eight shallow-step monument, rising into the air at an angle of 49°.

Egyptologists believe that this would have been an elongated step pyramid if the remaining side had not been left uncovered.

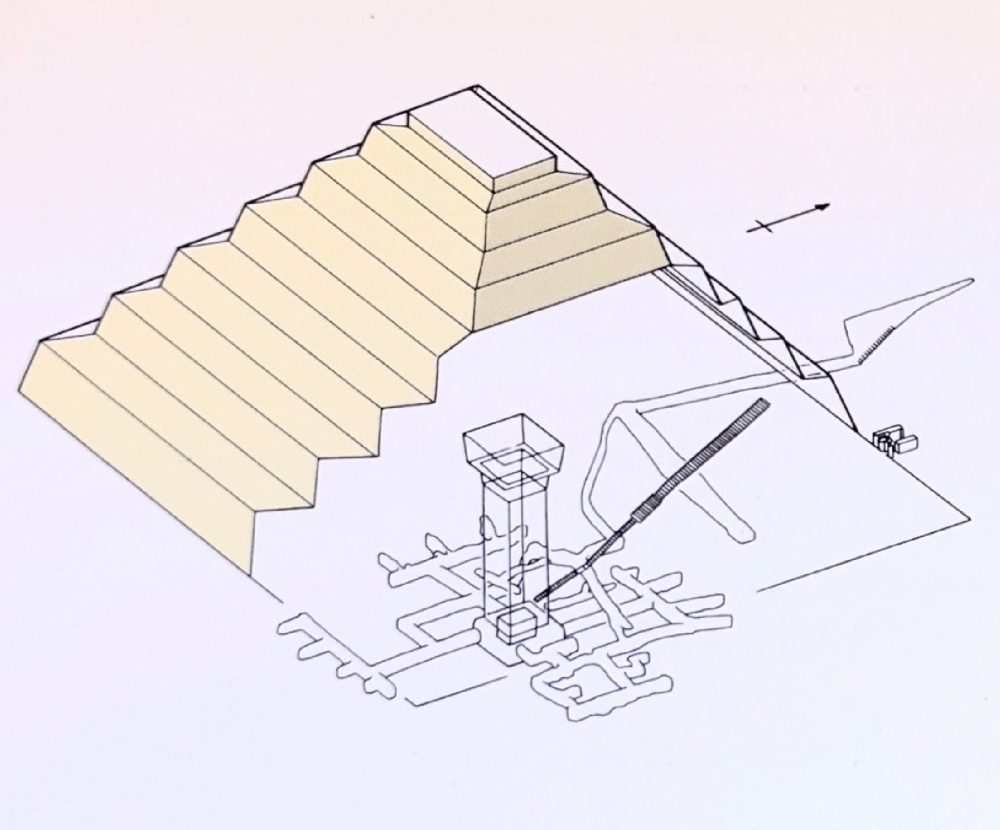

The Step Pyramid of Djoser is thought to have been completed in six distinct stages, which offers evidence that the monument commissioned by Djoser and constructed by Imhotep was an experimental structure.

The builders started, most likely, with a rough idea of what the Pharaoh wanted, and added to the structure throughout the years. Eventually, Imhotep produced what experts today hail as the earliest colossal stone building and the earliest large-scale cut stone construction in Egypt.

The Step Pyramid of Djoser completely revolutionized ancient Egyptian architecture, introducing an entirely new form of building, one that would prove to be far more lasting and more stable than mastabas, which were built of lesser materials.

Beneath the Pyramid, Imhotep also built a stunning subterranean world covering nearly six kilometers in length. This underground labyrinth was home to hundreds of rooms, magazines, and chambers.

Strangely, such a massive underground would never again be built in the history of Egyptian pyramids.

Lack of pyramid-building records

Even stranger is that the architect and his team never decided to write down how they planned and how they eventually built the pyramid.

There is a complete lack of pyramid-building records dating back to the third dynasty of Djoser.

Furthermore, although one would expect that a long line of similar pyramids would follow Djoser’s Step Pyramid, this was not the case. A few Pharaohs that succeeded Djoser to the throne tried replicating his astonishing monument but failed.

This changed in the Fourth Dynasty when a King called Sneferu became Pharaoh.

Sneferu would eventually become the greatest pyramid builder to ever live in Egypt, producing three magnificent “great” Pyramids.

Egyptologists credit Sneferu with the construction of the Pyramid at Meidum, and the Bent and Red Pyramids at Dahshur, the latter of which is the third-largest pyramid ever built in Egypt.

Sneferu’s pyramids directly influenced future pyramid design in Egypt. The Red Pyramid—Egypt’s first successfully smooth-sided pyramid set new standards just as Djoser’s Strep Pyramid Did.

Sneferus Red Pyramid at Dahshur laid down the foundations of the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza. But the curious part is there are no records that mention any of the construction processes involved in the construction of neither the Bent, Red, or Pyramid at Meidum.

Despite the importance of all three of Sneferu’s pyramids, we have no ancient papyri that make reference to Sneferu commissioning the pyramids, nor do we have any technical documents that tell us what the architects and engineers of ancient Egypt made use of when they were designing and building the pyramids.

This absence of written accounts is one of the most curious things about pyramid building in ancient Egypt, personally for me.

That’s why I agree with Egyptologist Ahmed Fakhry. He writes in his incredible detailed book “The Pyramids” that of all the problems concerning Egyptian pyramids, their construction is the most puzzling.

Fakhry explains that even in ancient Roman times, people were left awestruck by their size and complexity.

Writer Pliny, who condemned the pyramids as an “idle and foolish exhibition of royal wealth,” found much to be wondered at.

Pliny wrote that “the most curious questions is how the stones were raised to such a great height.”

As I have already explained, the Great Pyramid of Giza is home to two and a quarter million blocks of stone alone, some of which weighed as much as 60 tons. The imagination is staggered by the work involved, even if done with MODERN equipment. However, one must always bear in mind that the ancient Egyptians built these ancient wonders with the simplest methods available in their time; even the pulley was unknown in Egypt before the Roman period.

As explained by Fakhry, both in quarrying and building, the builders of the pyramids used copper chisels and probably iron tools, as well as flint, quartz, and diorite plunders that aided them in quarrying the stone.

The only additional tools they likely used were large wooden crowbars and, for transportation, wooden rollers and sleds.

But I find it highly interesting that Fakhry notes how moving blocks that weighed between eight and ten tons and some even larger than that was not considered a difficult task by the ancient Egyptians, who later would transport the colossus of Ramesses to the Ramesseum at western Thebes. This supermassive statue, made from one block of stone, had an approximate average of one thousand tons.

Fakhry notes that “indeed, the process of quarrying, transporting, and erecting these monuments was such an ordinary matter that the Egyptians did not consider it worthy of record.”

He adds that ” most of the information we have is based on the study of monuments themselves, especially those that were left unfinished by their builders.”

I find this lack of records beyond interesting.

Merer’s Journal and the Pyramid

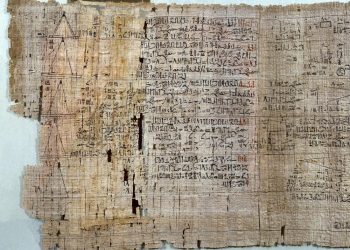

This leads me to an ancient document dubbed Diary of Merer (Papyrus Jarf A and B).

This is a papyrus logbook that was dated to be around 4,500 years old. Its translation revealed it to be the record of the daily activities of stone transportation from quarries at Tura (across the Nile) to Giza.

The importance of the papyri resides in the fact it is considered the oldest with writing ever found.

It was discovered seven years ago by a French archaeological mission in a cave on the Red Sea coast.

Written in both hieratic and hieroglyphs, the ancient text mentions, among other things, the diary of a middle-ranking official called Merer, who worked as an “inspector” in the 26th year of the reign of King Khufu.

ONE: The journal makes reference to several months of work involved in the transportation of limestone blocks from Tura to Giza.

This collection of papyri has been used by many “experts” and media outlets throughout the years as “conclusive evidence” of ancient texts that “mention how the Great Pyramid of Giza was built.”

However, regrettably, it is far from that. The truth is that we’ve adopted the notion that Merer’s journal “describes” how the pyramid was built. TWO: The diary does not specifically say where the stones were used or for what purposes.

However, and as revealed by Egyptologists, given that the ancient papyri may date to what is widely believed to be the end of Khufu’s reign, the stones may have been used for cladding the outside of the Great Pyramid.

THREE: The journal describes how, about every ten days or so, two or three trips were made from Tura to Giza and that Merer oversaw the transport of up to 200 blocks of limestone per block. While this is certainly fascinating information, for all we know, the blocks of limestone may have been used for a construction project entirely unrelated to the pyramid, or the Giza plateau.

The limestone blocks may have been transported elsewhere. More importantly, I believe that the limestone blocks may have also been used for the restoration of the pyramid.

Join the discussion and participate in awesome giveaways in our mobile Telegram group. Join Curiosmos on Telegram Today. t.me/Curiosmos