Around 3,000 BC, an ancient Sumerian astronomer meticulously recorded his nightly observations on a clay tablet—a star map that captured the celestial wonders above. On one fateful night, as he noted the usual positions of planets and stars, something unusual caught his eye. A bright, moving object, absent from previous records, emerged in the heavens.

Uncovering an Astronomical Treasure

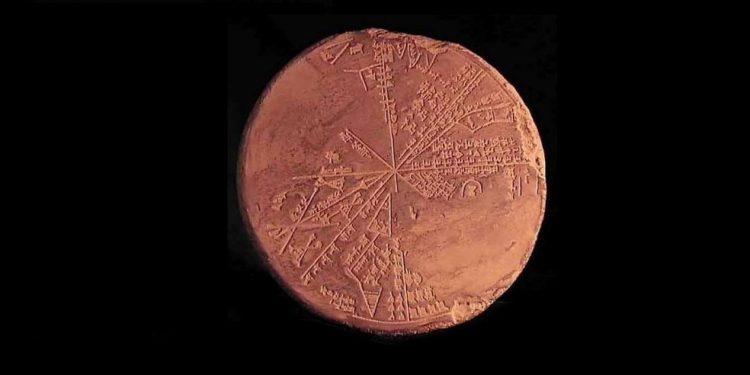

Discovered in the underground library of King Ashurbanipal in Nineveh during the 19th century, this 5,100-year-old clay tablet is now celebrated as an astronomical treasure. Cataloged as artifact No. K8538 and held at the British Museum, the tablet offers a window into over five millennia of celestial observation in ancient Mesopotamia.

Recent breakthroughs using advanced computer simulations have allowed researchers to reconstruct the ancient night sky with remarkable accuracy. Through this digital lens, scientists decoded a message inscribed by a Sumerian sky-watcher—a message detailing the approach of a massive cosmic visitor.

The Celestial Warning: “A White Stone Bowl”

The tablet is not just a map of constellations; it is a chronicle of an extraordinary event. The ancient astronomer described the incoming object as “a white stone bowl approaching from the sky.” According to the translated text, on 29 June 3123 BC, this massive asteroid was observed hurtling towards Earth, its trajectory recorded with an astonishing precision of less than one degree.

Modern simulations based on these ancient notes suggest that the asteroid—estimated to be around one kilometer in diameter—likely impacted Europe. Many experts believe the cosmic body may have struck near Kofels in Austria. The star map’s detailed record of celestial positions and weather conditions at the time enabled scholars to trace the asteroid’s path and understand the dynamics of its impact.

The Impact That Changed Everything

The tablet further explains why no prominent impact crater has been found. It appears that the asteroid’s shallow angle—reported to be as low as six degrees—caused it to clip a natural formation, likely the summit of Gamskogel. This glancing blow created an enormous pressure shock that pulverized the space rock, effectively erasing the evidence of a catastrophic impact.

This ancient Sumerian star map not only reveals the sophistication of early astronomical observations but also highlights the incredible precision achieved by ancient scholars. Their ability to capture complex celestial events offers modern researchers invaluable data, bridging a gap of thousands of years. Today, the tablet stands as a testament to humanity’s long-standing fascination with the cosmos and the enduring quest to understand our place in the universe.