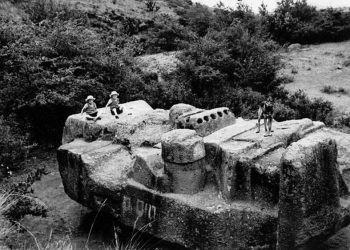

Before the British Isles became islands, a vast stretch of land connected them to the European mainland. That land was Doggerland, a now-submerged world that once teemed with life — a place of rivers, forests, and human settlements that thrived for thousands of years before it disappeared beneath the sea.

Sometimes called the “Atlantis of the North,” Doggerland is no myth. Archaeologists have found bones, tools, and even traces of settlements beneath the North Sea — clues to a lost chapter in human history. And now, thanks to new data pulled from the seabed, we’re learning more than ever before about this hidden world.

Uncovering the prehistoric world beneath the waves

In recent years, researchers from Wessex Archaeology retrieved one of the most complete sets of seabed cores ever extracted from the southern North Sea. These long, cylindrical samples contain thousands of years of sediment and organic material — a time capsule of environmental change.

“We’ve recovered what we believe is a unique sequence of sediments offering an environmental record spanning nearly 3,500 years,” said Dr. Claire Mellett, a principal marine geoarchaeologist at Wessex.

The cores reveal an unbroken story of Doggerland’s transformation — from fertile plains to wetlands, and finally to the ocean floor. They offer new insights into how rising sea levels after the last Ice Age reshaped the land and the lives of those who called it home.

What Doggerland was really like

Roughly 18,000 years ago, during the last glacial maximum, much of Britain and northern Europe was buried under sheets of ice. As the climate warmed, the ice retreated, exposing a vast land bridge between modern-day England and continental Europe.

Doggerland became an ideal environment for human habitation. Temperate grasslands, rich with game like mammoths and deer, supported nomadic hunting groups. Over time, the landscape changed again — rivers and marshlands appeared, and Mesolithic communities settled near estuaries, taking advantage of abundant fish, birds, and edible plants.

Archaeological finds pulled from the North Sea have included flint tools, spear points, animal bones, and even pollen grains — evidence of a vibrant and evolving ecosystem.

To me, what makes Doggerland so fascinating isn’t just that it existed — it’s how it disappeared. As global temperatures rose, melting glaciers caused sea levels to rise, flooding low-lying areas. Doggerland was gradually swallowed by the sea, with the final flooding likely triggered by a massive tsunami caused by the Storegga Slide, a submarine landslide off the coast of Norway, around 8,200 years ago.

By then, much of the land had already been transformed into a patchwork of islands, marshes, and shallow bays. But this final event may have abruptly erased what remained — and forced its last inhabitants to flee.

What lies beneath

Doggerland might be long gone, but what’s buried beneath the North Sea still has a lot to teach us. The more scientists uncover, the more we learn about how people handled environmental changes thousands of years ago — changes that, in some ways, aren’t so different from what we’re facing now.

By analyzing layers of sediment pulled from beneath the North Sea, scientists are learning what life was like there thousands of years ago. These layers reveal how the environment evolved as the Ice Age ended, offering clues about how rising sea levels reshaped the land and the lives of the people who lived on it.

That kind of research doesn’t just tell us about the past. When you think about it, it helps us think about the present, too. As today’s coastlines face similar challenges from sea level rise, studies like this give us a longer view of how humans have dealt with changing conditions before.

Much of Doggerland still lies unexplored, but new tools like seabed scanning and environmental DNA sampling are giving researchers a way to piece together what the region once looked like. Some of the most detailed data so far has come from sediment cores collected during offshore wind farm projects, covering more than 85 square kilometers.

As scientists continue to study the material, they may find remains of homes, hearths, or other traces of the people who once lived there. So far, the evidence paints a picture of a land that was rich in resources and well-used by the Mesolithic communities who called it home.