The idea of alien technology arriving on Earth has often belonged to science fiction. But now, some scientists are hunting for alien technology in Earth’s oceans with real expeditions, physical evidence, and peer-reviewed methods. Their focus is not the stars, but the seafloor, where something may have already crashlanded.

In 2023, off the northern coast of Papua New Guinea, a research team led by Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb completed a month-long expedition to recover fragments of an object that crashed into the Pacific almost a decade earlier. Known as IM1, the object is believed to have originated from outside the solar system. The team recovered hundreds of small metallic spheres from the volcanic sediment. These spherules are the center of a growing scientific debate about their possible origin.

A fireball from beyond the solar system

On January 8, 2014, U.S. Department of Defense sensors recorded a high-speed fireball entering Earth’s atmosphere. It exploded in the air near Manus Island, Papua New Guinea. The object’s velocity was extreme, measured at over 40 kilometers per second. Its steep entry angle and speed suggested that it was not gravitationally bound to the Sun. That made it interstellar.

The data remained classified for years. In 2022, U.S. Space Command confirmed that the object, formally named CNEOS 2014-01-08 (IM1), had indeed come from outside the solar system. This made it the first confirmed interstellar object to impact Earth, three years before ‘Oumuamua passed through the inner solar system. But unlike ‘Oumuamua, IM1 didn’t simply fly past. It struck the atmosphere and broke apart.

Loeb, who had already drawn controversy by suggesting that ‘Oumuamua might have been an alien probe, began developing a plan to recover whatever was left of IM1 from the ocean floor.

Into the Pacific: the completed search for IM1’s remains

In June 2023, Loeb and his team boarded the research vessel Silver Star and traveled to a narrow stretch of ocean roughly 100 kilometers north of Manus Island. Their goal was clear. If IM1 had survived its fiery entry and exploded over the sea, then fragments might still be preserved in the sediment.

The team deployed a magnetic sled designed to collect metallic debris from the seafloor. Over several weeks, they dragged the sled across a search area more than one and a half square kilometers in size. Each pass brought up sediment that was filtered and inspected in the ship’s onboard lab. The work was slow and methodical.

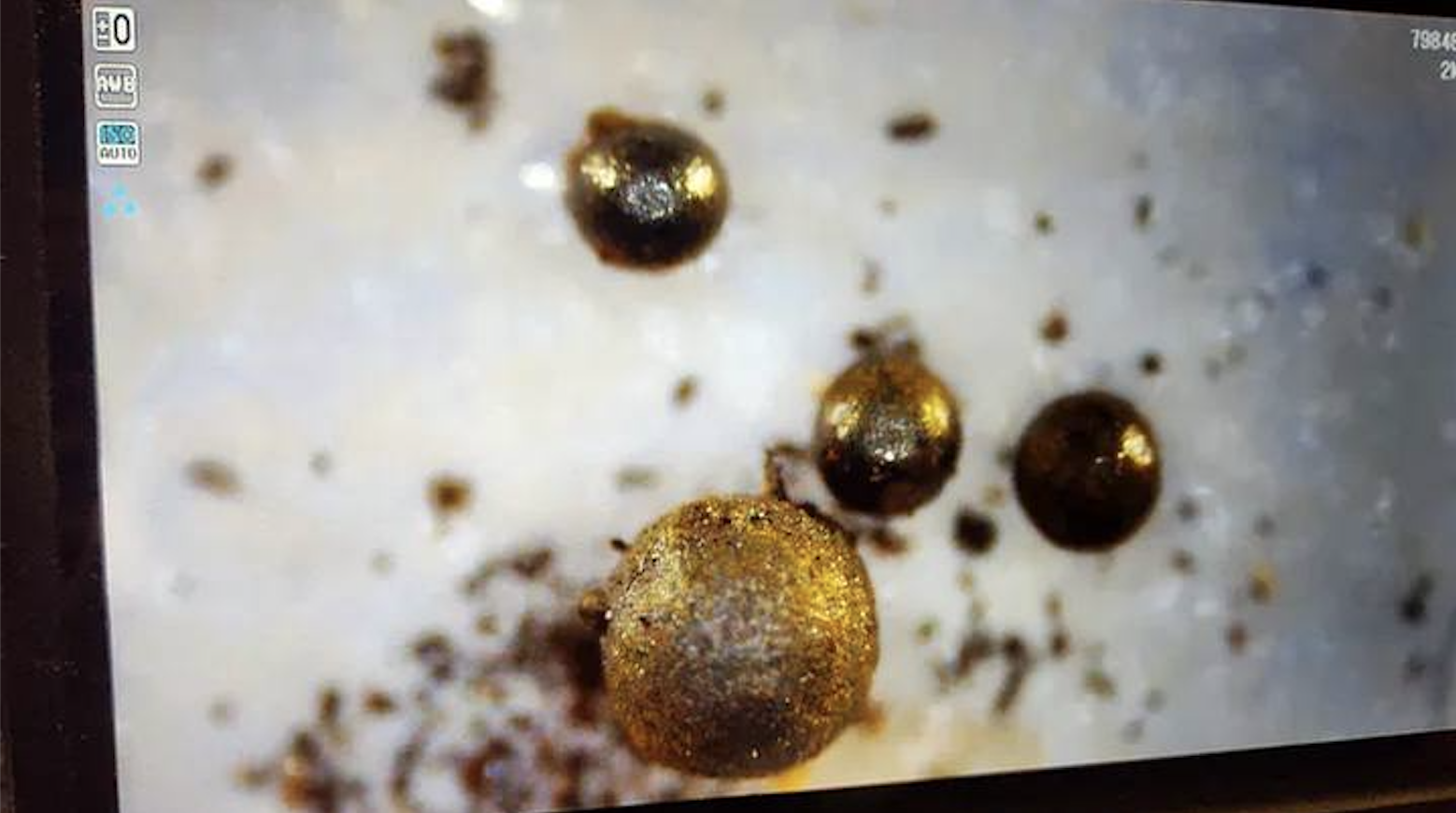

In total, they recovered 700 tiny metallic spherules. Most were smooth and round, no more than a millimeter across. Under the microscope, they resembled industrial ball bearings or micro-welded beads. But chemical analysis showed otherwise.

Hunting for alien technology in Earth’s oceans

The spherules contained high concentrations of iron, magnesium, and nickel, along with trace elements such as beryllium, lanthanum, and uranium. According to Loeb, their composition does not match any known class of meteorite, nor does it reflect typical industrial waste. Some were unusually hard and resistant to corrosion. Others showed microstructures that hinted at rapid cooling in high-energy environments.

Loeb has not claimed they are alien technology. He has said that the fragments might be artificial and may represent engineered materials of interstellar origin. That distinction matters. The evidence is not conclusive. But the recovered objects are real, and they differ from any known terrestrial or meteoritic samples, according to Loeb.

For Loeb and his colleagues, the discovery justifies continued investigation. Hunting for alien technology in Earth’s oceans, they argue, is not a fringe idea but a scientific effort to treat unusual materials seriously. The next steps include peer-reviewed publication, expanded testing, and planning for a second, more advanced expedition to the region.

The ocean as the quietest frontier

The reason scientists are hunting for alien technology in Earth’s oceans is not just because of IM1. It is also because the ocean itself is uniquely suited to conceal long-term visitors. The deep sea is cold, dark, and largely unexplored. More than 80 percent of the ocean floor has never been mapped in high resolution. Much of it remains invisible to satellites and sonar.

Water insulates thermal signatures. It blocks many forms of radiation. It absorbs light. For any intelligence wishing to observe Earth quietly, the deep ocean would be a logical location to operate from or hide within.

In recent years, some researchers have started looking beneath the waves rather than beyond the stars. The effort to search Earth’s oceans for non-human artifacts combines elements of oceanography, materials science, and astronomy. Instead of treating the sea as a biological frontier, this approach frames it as a potential archive, a place where evidence of past contact could remain hidden in physical form. This leads me to the next important thing.

A history of unexplained objects underwater

Reports of unidentified submerged objects, or USOs, go back decades. Submariners during the Cold War described sonar contacts moving at speeds beyond any known underwater craft. Pilots have reported aerial objects entering the sea without impact or disruption. In 2019, footage from the USS Omaha showed a spherical object descending into the ocean west of San Diego. It left no visible debris and has never been explained.

These encounters have rarely led to recovery. Most remain anecdotal or classified. But their consistency has led some researchers to consider the possibility that Earth’s oceans are not just empty zones of water but a domain where advanced technology could operate unseen.

From signals to fragments

The traditional search for extraterrestrial intelligence has focused on the sky. Radio telescopes scanned for signals. Optical observatories looked for laser pulses or unusual transits. But after decades of listening, no clear signal has ever arrived.

The discovery of IM1 and the recovery of physical fragments from the ocean floor mark a new approach. Hunting for alien technology in Earth’s oceans means searching for material evidence, alloys, components, or structures that suggest manufacture, not just chemistry.

This shift is profound. In fact it is as profound as when we decided to treat UFOs as a real thing, and not just a conspiracy theory.

It redefines what a technosignature might be. Instead of a broadcast, it could be a sphere of hardened iron buried in Pacific sediment. Instead of a message from light-years away, it might be a millimeter-sized object already on Earth.

The sky has not answered. So now, scientists are turning to the sea. Hunting for alien technology in Earth’s oceans is not about fantasy. It is about examining the places we have ignored, the signals we may have missed, and the debris that might already be here. I believe that if we focus more on the ocean, the ocean floor, we will perhaps come one step closer to answering the question “are we alone?”