All across the world, ancient civilizations carved sacred doorways into stone and did so with a level of skill that continues to confound experts.

Across deserts, cliffs, and remote valleys, we find something strange, doorways carved directly into solid rock. Some are tall and narrow, others wide and geometric. They’re not part of buildings. They’re not leading anywhere. But they were made with care — and in many cases, with precision that’s hard to believe.

They weren’t just symbolic. In some places, they seem to mark something important, a ritual space, an alignment, or maybe a boundary between worlds.

The real mystery is this: many of these structures were carved long before steel tools existed. And yet, the work is so clean, so deliberate, it’s hard to imagine how they pulled it off.

What Tools Were They Really Using?

It’s often said that early stonemasons shaped stone using little more than copper chisels, stone hammers, and sand. And in many cases, especially with softer rock like limestone or sandstone, that probably worked. Slowly, methodically, and with a lot of patience.

But granite? Andesite? Diorite, a rock dense enough to dull modern steel? That’s a different story.

These are the materials where the usual explanations fall apart. Some of the most precisely carved ancient structures were made from stones like these — the kind that require diamond-tipped tools today. At sites in Egypt, Peru, and Bolivia, we see clean cuts, sharp inner corners, and surfaces that aren’t just smooth but nearly polished. In some places, the edges are so precise they look as if they were shaped by machines. And strangest of all, there are often no clear signs of the tools that were used.

So how did they do it? If ancient civilizations carved sacred doorways into these stones, were they using techniques we’ve lost or methods we still haven’t identified?

The Precision Behind Egypt’s False Doors

Step inside a tomb from the Old Kingdom, and you’ll likely find a strange feature on the wall,a doorway that leads nowhere. It’s flat, symbolic, carved from solid rock, and known today as a “false door.” These were meant to represent passageways for the spirit of the deceased. But symbol or not, the workmanship is real.

Many are carved into granite, one of the hardest stones on Earth. And they weren’t just sketched and chipped into place. The lines are sharp and clean. The geometry is perfect. In some cases, the polish is so fine it reflects light. These weren’t casual religious symbols. They were deliberate, methodical, and crafted with incredible control.

And here’s the strange part: some were carved deep inside chambers with limited access, in spaces where it would have been nearly impossible to position large tools or work freely. Yet somehow, the quality never falters.

What we see in Egypt is more than artistic dedication. It’s technical excellence that still holds up after 4,000 years.

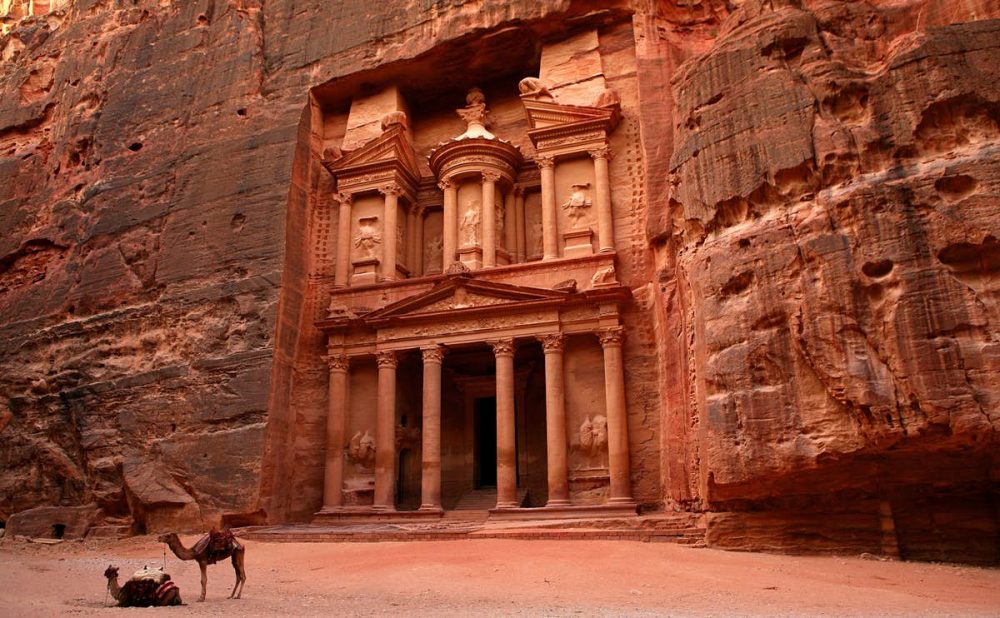

Petra’s Doorways Were Carved, Not Built

High in the sandstone cliffs of Jordan, the ancient city of Petra hides one of the most iconic facades in the world. The Treasury — with its massive columns, steps, and triangular pediment — looks like it was constructed from stacked stone. But it wasn’t built. It was carved.

The Nabataeans didn’t assemble Petra, they etched it from the living rock.

Some of the entrances rise 20 meters high, cut into vertical cliff faces. The architectural detail is staggering. What looks like separate blocks, beams, and architraves are all part of a single piece of stone. That illusion,of something built from parts, is part of Petra’s mystery. And achieving it meant working with extreme foresight and planning.

The symmetry is flawless, even though no modern scaffolding or leveling systems were available. Everything was done from the top down. Any mistake would have been permanent.

The sheer ambition of Petra’s doorways shows us something else too, this wasn’t just about creating a space. It was about creating a message. And the message had to last.

Puma Punku and the Mystery of the Incomplete

In Bolivia, at over 3,800 meters above sea level, lies one of archaeology’s most perplexing sites: Puma Punku.

The stonework here is different. It’s not decorative or spiritual … it’s mechanical. The blocks are shaped with notches, channels, and perfectly squared edges that lock together like components of a machine. Some feature geometric recesses that seem to be part of a modular system. This isn’t random design. It’s premeditated engineering.

Andesite and diorite — the primary stones used — are incredibly hard. To carve them with hand tools would take enormous effort, yet the results look effortless.

What’s even more fascinating is that some blocks were never finished. They were left mid-cut. Not in a crude or rough way, but in a way that shows the cut simply stopped, as if something interrupted the process. The unfinished stones are perhaps the clearest window we have into how the work was done. And that window suggests something much more advanced than trial-and-error hammering.

To this day, no one has reproduced the work with the tools believed to be available at the time.

Doors That Don’t Lead Anywhere

At some sites, the mystery isn’t just how the doorways were made, it’s why.

In Peru, the site of Hayu Marca features a doorway carved into a flat rock face. There’s no room behind it. No chamber. No interior passage. It’s just a door to nothing. Or maybe, to something we’ve forgotten.

Locals call it the Gate of the Gods. According to Andean legend, it’s a portal. A priest from ancient times is said to have walked through it carrying a sacred object and vanished.

Whether or not the story is true, the design is precise. The shape is unusual: a large rectangle with a smaller inset frame at its base. It stands alone in the landscape, but not randomly. Its alignment with the horizon and specific solar points has led some researchers to believe it was built with astronomy in mind.

Other doorways across the ancient world share similar qualities. They’re placed in hard-to-reach spots. They face the sun or stars at specific times of year. Some seem to “mirror” other sites miles away. It’s as if they were part of a larger system a network, not of roads, but of meaning.

What’s Left Behind — and What It Tells Us

For all our machines, our measurements, our digital models, we still don’t know exactly how these doorways were made. The stones remain. The precision is real. The alignment, the geometry, the craftsmanship, all of it is there in the rock. What’s missing is the method.

No texts explain the process. No tools have been recovered that would make the work make sense. What we have are the results. We see structures that suggest planning, skill, and knowledge that go far beyond what most people associate with the ancient world.

It’s easy to underestimate ancient builders. But maybe the problem isn’t that we give them too much credit. I think that maybe we haven’t given them enough. These doorways weren’t made for decoration. They were carved with intention. And if we can’t explain how they were built, then maybe it’s time we looked harder at why they were built at all.

That might be where the real answers begin.