Modern engineering spends billions to protect cities from earthquakes. But ancient builders may have mastered earthquake-proof stone structures long before rebar or seismic codes existed.

Some of the world’s oldest buildings have stood through devastating earthquakes for centuries or even millennia. From Peru’s Machu Picchu to Japan’s wooden pagodas, these ancient marvels reveal clues that suggest their builders developed intuitive, practical methods to survive seismic forces.

In a time without modern materials or scientific theory, how did they create earthquake-proof stone structures that endure when many contemporary buildings fail?

How earthquake-proof stone structures really work

Designing buildings to withstand earthquakes means accounting for sudden lateral forces, unpredictable ground shifts, and intense vibration. Structures need to move, flex, or absorb shock rather than resist it head-on.

Today’s architects use base isolators, steel reinforcements, and high-tech damping systems. But in the ancient world, none of that existed.

And yet, some builders consistently achieved what we now call earthquake-proof stone structures, using only natural materials and empirical knowledge. These principles included:

-

Dry masonry with interlocking stones that allowed slight movement without breaking

-

Tapered or inclined walls that added balance and stability

-

Layered foundations using earth, gravel, or sand to absorb shocks

-

Symmetry and weight distribution to prevent torsional stress during shaking

These weren’t one-off accidents. They were intentional strategies passed through generations of builders who had learned by watching what survived.

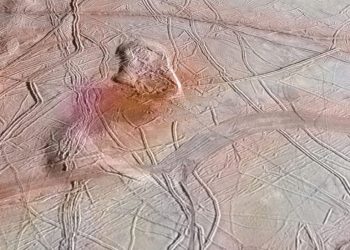

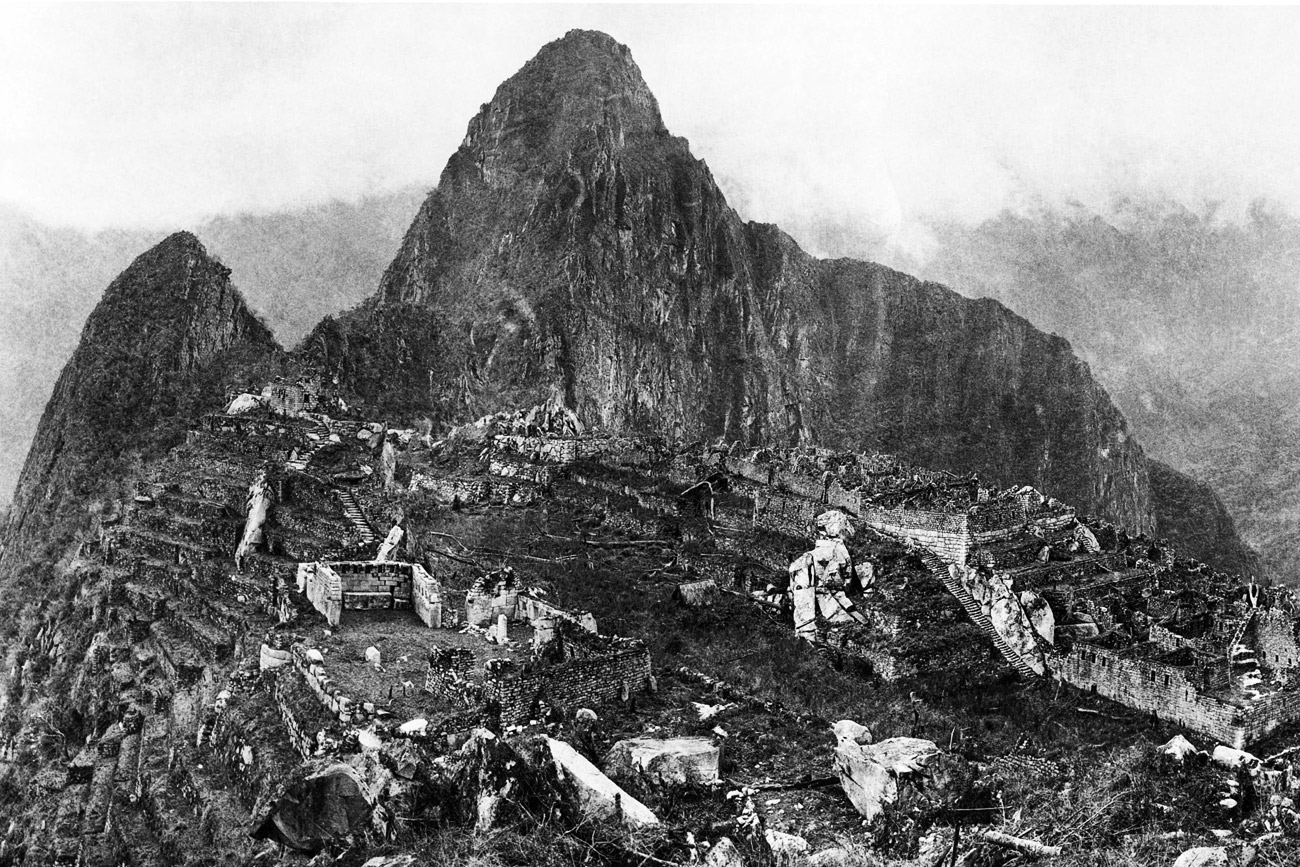

Machu Picchu: Stone blocks that move without breaking

The Inca city of Machu Picchu, built in the 15th century in the seismically active Andes, is a prime example of earthquake-proof stone structures.

Inca masons used ashlar masonry, cutting stones so precisely that they fit together without mortar. These stones aren’t just locked together — they’re carved to move slightly during seismic events, then settle back into place without cracking.

The Inca also sloped their walls slightly inward, creating a self-stabilizing effect. This subtle design choice has helped the city endure both powerful earthquakes and constant erosion.

Archaeologists believe Inca builders rebuilt and improved structures after seismic damage, constantly refining their knowledge. Today, Machu Picchu remains one of the world’s best-preserved examples of ancient seismic design.

Teotihuacan: Earthquake-proof planning in Mesoamerica

North of modern-day Mexico City lies Teotihuacan (one of my favorite ancient sites), a sprawling ancient metropolis founded around 100 BCE. This region is also one of the most earthquake-prone in the Americas — and yet, Teotihuacan’s pyramids remain standing.

The Pyramid of the Sun and Pyramid of the Moon were built with a layered system: volcanic stone, compacted rubble, lime plaster, and large stone blocks. This mix helped absorb shocks and redirect forces.

Some archaeologists argue these pyramids incorporated “floating floors” — layers of compressible materials that worked like basic seismic isolators.

The city’s planning also helped. Buildings were aligned along natural terrain contours, reducing structural stress. Together, these features suggest a remarkable early understanding of how to build earthquake-proof stone structures.

Japan’s pagodas and kofun tombs: Built to move, not resist

Japan has a long history of deadly earthquakes, yet some of its wooden pagodas have survived for over 1,300 years. How?

Pagodas like Hōryū-ji, built in the 7th century, use a central column known as the shinbashira. This vertical shaft acts as a shock absorber, swaying during a quake and stabilizing the surrounding structure.

These buildings are also constructed without nails. Instead, flexible wooden joints allow each level to shift independently. The result is a structure that doesn’t fight movement — it uses it.

Underground, Japan’s kofun tombs demonstrate another method. Their chambers are carefully layered with alternating materials to dampen ground motion. It’s a different approach, but with the same result: resilient architecture designed to survive seismic events.

Global evidence of ancient seismic knowledge

Remarkable examples of earthquake-proof stone structures exist far beyond the Andes and Japan:

-

Petra, Jordan: Most buildings were carved directly into cliffs. Without joints or seams, they’re nearly immune to collapse.

-

Sri Lanka: Ancient stupas sit on layered foundations of sand and soil. This acts as a cushion that absorbs shock.

-

Greece: Classical temples used segmented columns connected by metal dowels, allowing for slight shifts. Bases often included porous stone to disperse vibration.

-

India and Iran: Temples featured corbelled roofs and flexible brackets to reduce strain on walls and ceilings.

-

Armenia: Monasteries incorporated seismic joints and “rocking stones” that allowed structures to move independently during a quake.

In all these cases, builders developed practical techniques tailored to their materials, geography, and observed patterns of destruction.

How did ancient builders learn to protect against earthquakes?

Ancient civilizations didn’t have seismographs or engineering handbooks. What they did have was time, careful observation, and a long memory.

Their knowledge wasn’t written down in manuals. It was passed from one generation to the next through stories, hands-on experience, and learning by doing. When a building collapsed, they didn’t just rebuild it the same way. They made it better.

In many cultures, stories and rituals about earthquakes weren’t just myths. In fact, they often carried real lessons about how to build safely. Hidden in the symbolism were practical insights that helped guide future builders.

In places like the Andes or Japan, building wasn’t seen as just a trade. It was something closer to a calling. Skilled builders were respected not just for their craftsmanship, but for holding onto knowledge that kept communities safe. They understood the land, the materials, and how to work with nature instead of against it.

Can ancient techniques still help us today?

Modern cities rely on steel, concrete, and digital sensors to keep buildings safe during earthquakes. But when you look at how long some ancient stone structures have stood, it becomes clear that you don’t always need advanced technology to build something strong and resilient.

Today, some engineers are going back to study those older techniques. Inca masonry is being explored as a model for affordable, low-carbon housing in earthquake-prone regions. Traditional Japanese joinery, designed to flex and move with the ground, is inspiring new ideas in sustainable construction.

This isn’t about turning away from modern science. It’s about bringing ancient knowledge into the conversation. In many parts of the world where high-tech solutions aren’t available or affordable, these older building methods could still make a real difference.

Some of the strongest earthquake-resistant buildings ever made weren’t designed with computers or formulas. They were built by people who understood the land, paid attention to what worked, and passed that knowledge down through generations.

As earthquakes continue to pose serious risks around the world, the lessons from the past are more important than ever. Real strength doesn’t always come from complexity. Sometimes, it comes from working with the ground instead of against it.