There’s an ancient city in Syria that is said to be one of the oldest cities globally, so old that it even predates the Egyptian pyramids. Called Tell Brak, this ancient city dates back to when history itself was not being written.

It is older than old, so ancient that it predates the most ancient Egyptian pyramids by around 4,000 years. The city known today as Tell Brak remains shrouded in mystery.

Although we don’t know what the settlement was called more than 8,000 years ago, evidence suggests that people referred to the city as Nagar at one point in history.

Despite being one of the most ancient cities on the planet’s surface, its history, evolution, and fall have been anything but clear for historians. In fact, we didn’t even know the city existed until old Spy satellites from the US snapped images of the desert in the middle east, revealed the faint remnants of an ancient city. This ancient site is one of the best examples of archeology aided by aerial photography.

Tell Brak; an ancient city older than the pyramids

Imagine all the treasures that remain hidden beneath the surface, waiting to be spotted, uncovered, and revealed to the world.

The remnants of the ancient city were photographed by a US spy satellite and located in 50-year-old imagery by Dartmouth College anthropology professor Jesse Casana.

Professor Casana spent years studying and analyzing Corona Spy photographs of the Middle East.

These images are of great importance because 50 years ago when the images were snapped, the countryside was much less industrialized than today. The researcher and his colleagues documented around 10,000 previously unknown archeological sites thanks to the Corona Spy images.

The U.S. ran the CORONA spy satellite program between 1959 and 1972. During this time, the spy planes crisscrossed the skies snapping countless images o military infrastructure and innumerable archaeological sites.

A city buried by sand and history

The remnants of the city are located in the Khabur plain, a region in northeastern Syria, not far from the borders of Turkey and Iraq.

Considered one of the largest ancient sites in what is known as northern Mesopotamia, an ancient settlement predating the city is known to have existed as far back as 6,000 BC. This means that more than 8,000 years ago, people already settled in the area.

Erected in a strategic position, Tell Brak is was built on a major route from the Tigris Valley northwards to the mines of Anatolia and westwards to the Euphrates and the Mediterranean. The city was likely highly regarded and acknowledged as an important commercial center, evidence of numerous workshops found at the site.

Excavations have also revealed evidence of mass production of bowls and other items made of obsidian and white marble. Stamp seals and sling bullets have also been excavated from the ancient city layers.

It suggests the cities inhabitants engaged in numerous craft activities, including basalt grinding, flint-working, and weapon making.

Archeological excavations also suggest that the urban-based society was based on rain-fed agriculture.

Seals recovered at the site have been dated to the pre-Akkadian kingdom and revealed the use of four-wheeled wagons and war carriages.

Although much of the city’s history remains shrouded in mystery, Contemporary cuneiform tablets excavated from Ebla suggest that during the third millennium Nagar was one of the dominant cities in this part of northern Mesopotamia. Moreover, scholars argue the city was also a major point of contact at the interface between the cities of the Levant in the west and those of Mesopotamia.

The earliest levels of the city that have been excavated are thought to date back to the mid-fifth millennium BC and include some of the most massive buildings of the site, some of which date back as far as the end of the Ubaid Period.

Nagar’s importance reflects its position at the western margins of Mesopotamia itself and controlling routes to the West and the Tigris and the south.

Although the city was of great importance and evolved greatly during the fourth millennium BC, it shrank in size at the beginning of the third millennium BC, just at the end of the so-called Uruk period, only to expand again around 2,600, precisely when it became known among people as Nagar.

Eventually, the ancient city became the capital of a regional kingdom that controlled much of the Khabur valley.

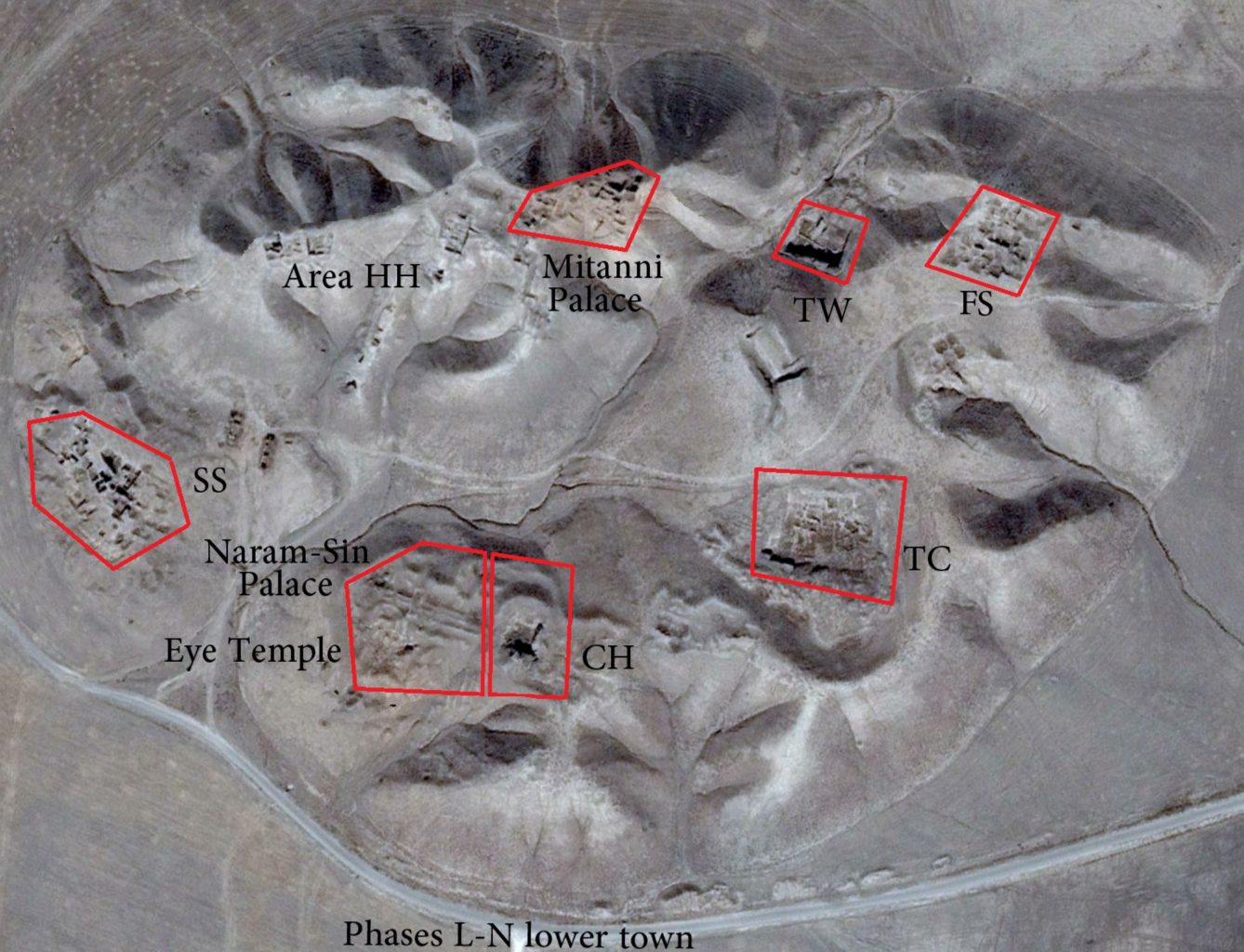

Today, the archeological settlement consists of a large—40 meter-high—central mound and various smaller “orbiting” mounds around it. The site covers a total area of nearly 300 hectares.

Archaeological excavations suggest a settlement of unknown—perhaps of a much smaller—dimension at the site before 4,200 BC. It was positioned at the center of the complex. However, its oldest remnants are buried deep beneath layers of buildings erected on top of it during later periods.

Although not many excavations have taken place at Tell Brak, the discoveries made by experts are nonetheless more than rewarding.

One of the most prominent discoveries made at the site is a non-residential structure that, according to experts, must have been gigantic. Although only a small part of the structure has been excavated, the building is thought to have had a large entrance with large towers covering its sides. Built with red mud bricks wall 1.85 meters thick, the remnants of the construction stand 1.5 meters today.

Radiocarbon dating of the structure suggests it existed around 4,400 BC.

The first excavations at the site took place in the 1930s by Max Mallowan, husband of Agatha Christie, who accompanied her husband in various excavations both in Syria and Iraq.

Mallowan’s central discoveries were the “Eye Temple” believed to date back to the 4th millennium BC, with its deposits of hundreds of small stone “idols,” and the “Naram-Sin Palace,” a discovery which confirmed that Mesopotamian political power was already there in the north during the 3rd millennium BC. The Naram-Sin palace was a huge storage and administrative building located at the southern edge of the city.

The ancient city was destroyed by the Assyrian empire around 1,300 BC, failing to regain its importance. As a result, it disappeared from history records during the early Abbasid era.

Join the discussion and participate in awesome giveaways in our mobile Telegram group. Join Curiosmos on Telegram Today. t.me/Curiosmos