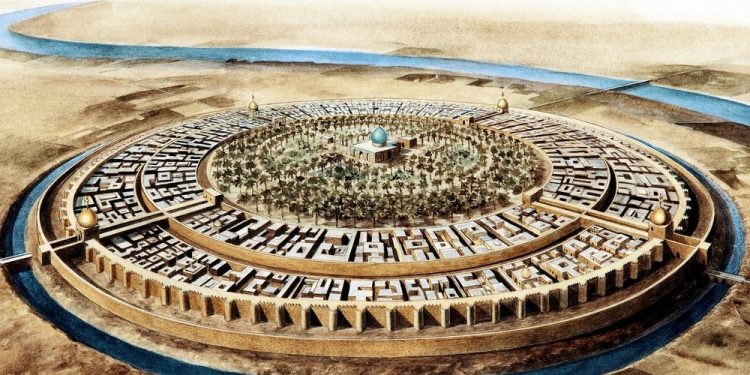

The round city of Baghdad was the Atlantis of Mesopotamia—an ancient circular capital engineered in the 8th century to reflect cosmic order, imperial ambition, and scientific mastery. Built by Caliph al-Mansur in the heart of ancient Mesopotamia, this lost city was designed to be the intellectual and political center of the Islamic world.

A forgotten circle at the heart of Mesopotamia

In the year 762 AD, deep in the land once known as Mesopotamia, Caliph al-Mansur began construction on one of the most unique cities ever built. It wasn’t just a capital. It was a perfect circle—a monumental experiment in geometry, symbolism, and power. Today, historians call it the round city of Baghdad. But to those who understand its scale, ambition, and legacy, it might just as well be remembered as the Atlantis of Mesopotamia.

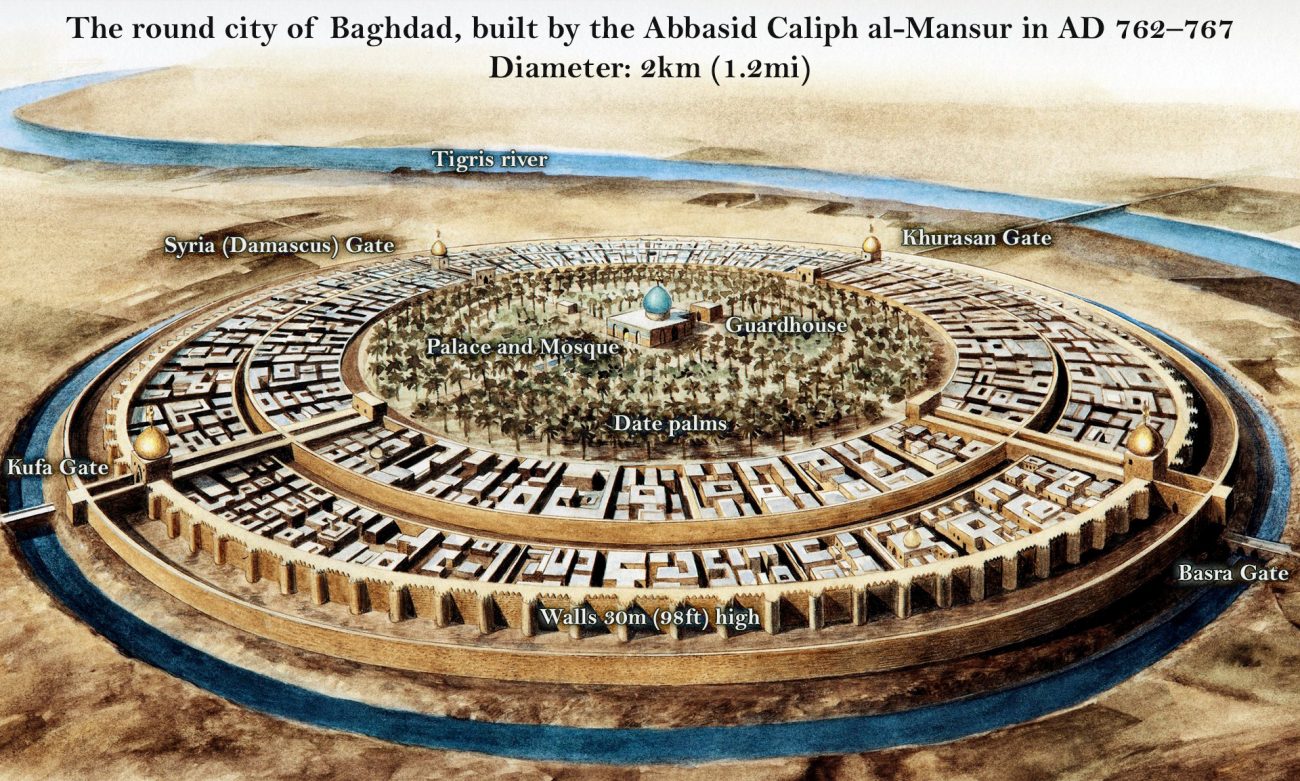

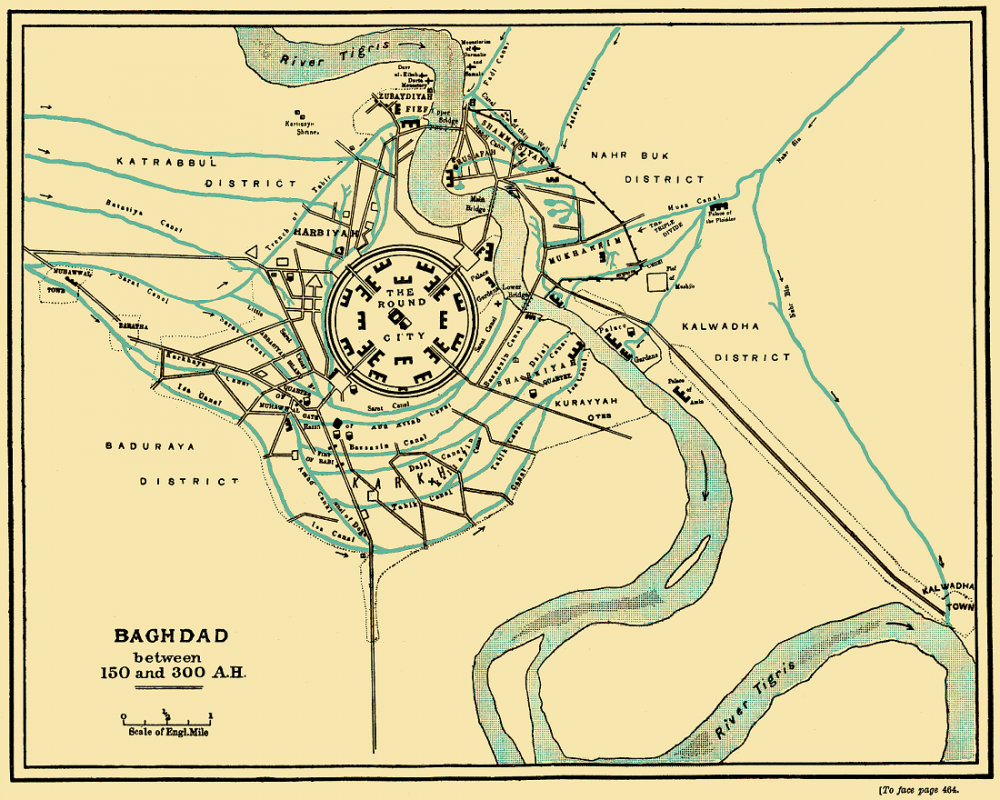

Al-Mansur didn’t choose the site lightly. He wanted a location with access to trade routes, defensibility, and spiritual resonance. He chose the banks of the Tigris River, a region once home to Babylon and Nineveh—ancient cities that had ruled vast empires long before the rise of Islam. From this historic ground, he would raise a new kind of city—one based not on random sprawl, but on calculated perfection.

The city’s construction began on July 30, 762, after astrologers determined the most auspicious date. That morning, al-Mansur prayed and ceremonially laid the first brick. He then commissioned more than 100,000 workers to build what some historians consider the most audacious city project in the Islamic world.

The round city of Baghdad was a mirror of the cosmos

Designed as a flawless circle two kilometers in diameter, the round city of Baghdad was meant to reflect the harmony of the universe. Al-Mansur, a lover of science and mathematics, was heavily influenced by the works of Euclid. His architects used geometric principles to plan every inch of the city. It was intended to be both defensible and symbolic: an earthly manifestation of cosmic order and divine rule.

The walls of the round city rose in concentric circles, flanked by a massive defensive moat. At four equidistant points stood monumental gates: Bab al-Kufa, Bab al-Basra, Bab al-Khorasan, and Bab al-Sham. Each gate opened toward a major region of the empire, linking Baghdad with the rest of the Islamic world. These avenues converged at the city’s very heart.

At that center stood the Palace of the Golden Gate, where the caliph himself ruled. Beside it stood the city’s grand mosque. Surrounding them were administrative buildings, courtyards, and barracks, all laid out with mathematical precision. From above, the city resembled a cosmic diagram, with power and faith radiating outward from its nucleus.

Al-Mansur was proud of what he had created. “This is indeed the city that I am to found, where I am to live, and where my descendants will reign afterward,” he reportedly declared. And for generations, his descendants did rule—from within a circle of stone and meaning.

The Atlantis of Mesopotamia: lost, but never forgotten

Though Baghdad grew far beyond its original circular walls, the round city remained its spiritual core. Within its walls flourished the House of Wisdom, a legendary institution of learning that preserved and translated texts from Greece, Persia, India, and beyond. While the origins of the House of Wisdom remain debated—some attribute it to al-Mansur, others to Harun al-Rashid or al-Ma’mun—its presence within the round city cemented Baghdad’s status as a beacon of knowledge.

Here, scholars translated Plato, Aristotle, and Hippocrates into Arabic. They developed algebra, advanced astronomy, and debated the nature of the soul. The round city of Baghdad wasn’t just a political capital. It was a global brain—an engine of ideas that powered the Islamic Golden Age.

The city’s reputation spread across continents. By the 9th century, Baghdad was likely the largest city in the world, with a population surpassing one million. Foreign travelers were stunned by its scale, wealth, and intellectual life.

The 9th-century writer al-Jahiz, after visiting, wrote: “I have seen the great cities… but I have never seen a city of greater height, more perfect circularity, more endowed with superior merits, or possessing more spacious gates or more perfect defenses than Al Zawra, that is to say, the city of Abu Jafar al-Mansur.”

And yet, over time, the perfect circle was consumed. As Baghdad expanded, the round city was absorbed into newer neighborhoods, its walls dismantled, its gates forgotten. Today, few visible traces remain. Modern Baghdad has buried its ancient core.

But the concept—the ambition—remains powerful. The round city of Baghdad was a city ahead of its time. Its planners envisioned not just a place to live, but a place to think, to govern, and to reflect the cosmos itself.

A lasting influence from the cradle of civilization

Baghdad was built at the heart of ancient Mesopotamia, where cities had first risen thousands of years earlier. But unlike Babylon or Ur, the round city didn’t simply emerge. And I would like to add that the round city design was no accident. Every feature, from its perfect symmetry to the position of its gates, was carefully planned to express meaning and control. It became the first purpose-built megacity of the Islamic world and one of the most symbolically charged capitals in history.

While its original form no longer survives, the city’s legacy continued to shape urban design for centuries. Cities like Cairo and probably even Samarkand drew on its core ideas: balanced layouts, central mosques, public learning centers, and the belief that a capital could represent something larger than itself.

I think that the round city of Baghdad wasn’t just an impressive building project. I see it kind of like the expression of an idea: that a city could reflect the values of its time. Its layout, its center, even its walls were shaped by a vision of order, learning, and power drawn from both faith and science.