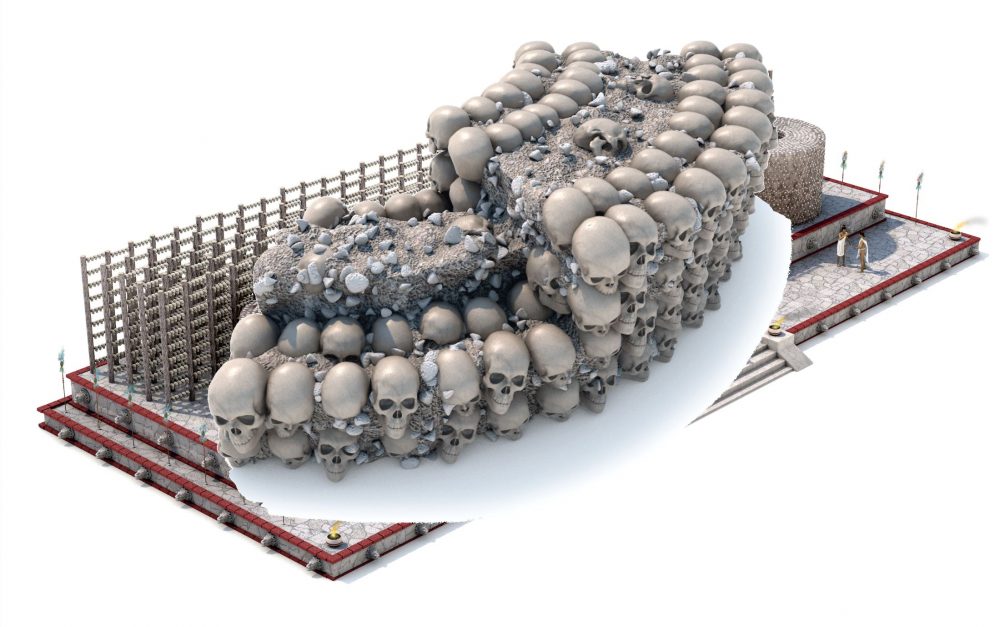

Beneath the heart of Mexico City, a group of archaeologists has unearthed a terrifying tower. It is no ordinary tower, but one made of human skulls. It’s called the Tzompantli, and it is the Aztec skull tower.

More than 650 skulls caked in lime have unearthed by researchers offer unprecedented views into Aztec rituals and religious practices. Not far from the gruesome tower, thousands of other fragments were found near the site of “The Templo Mayor“, one of the most important temples in Tenochtitlan; the Aztec Capital that later evolved into present-day Mexico City.

The ancient Aztecs—Mexica—erected their capital city on an island in the now-drained Lake Texcoco. At its zenith, the city is believed to have had a population of about 250,000 inhabitants and was the seat of an ancient empire that extended as far away as southern Mexico.

The temple complex in the middle of the island is thought to have been the political and religious heart of the city-state of Tenochtitlan.

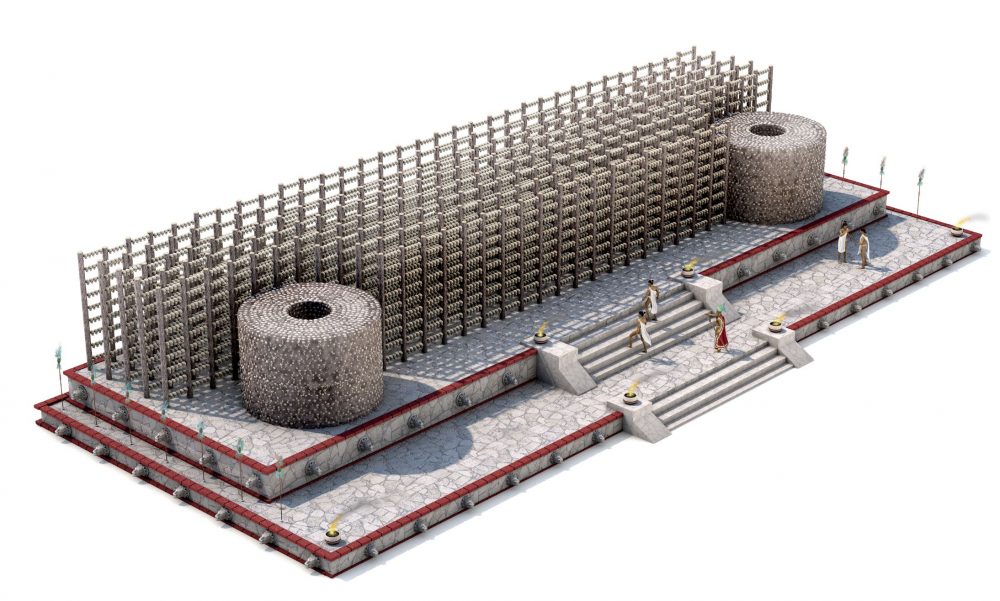

The terrifying skull tower is believed to form part of the Huey Tzompantli, a massive array of skulls that struck fear into the hearts of the Spanish conquistadores when they seized the city under the leadership of Hernan Cortes.

The tower of skulls, identified as the Huey Tzompantli was mentioned by Francisco Lopez de Gomara in ‘History of the conquests of Hernan Cortes.

The skull rack of the Aztecs, which served as a remained of death struck fear into the hearts of the Spanish. Scholars argue that the Aztecs expertly decapitated victims and carved standardized holes in the side of their skulls so they could be mounted onto the posts of a rack called the tzompantli which held thousands of skulls.

A terrifying skull tower

Gomara wrote:

Outside the temple and in front of the main gate, although farther than a stone’s throw, there was a skull rack with the heads of men captured in war and sacrificed by knife.

Shaped like a theater, longer than it was wide, the skull rack was made of stone masonry with tiers where the skulls were inset between stones with their teeth showing. The theater was flanked by two towers made of limestone and skulls facing outward.

Since the walls did not show any stones or other material, they were strange and colorful.

At the tip of the theater, there were seventy or more tall beams, separated from one another by about four or five palmos, and the space was filled with as many poles as they could fit from top to bottom, leaving some space between them.

These poles crossed through the beams, and each third of a pole had five. hears pierced through the temples.

Around 500 years passed by until researchers finally found the massive ossuary of which Lopez de Gomara was talking about in his book.

As history went by, scholars theorized that the skulls used in the terrifying skull tower were those belonging to the enemies of the Aztec Empire.

However, archeological discoveries shed light onto the Huey Tzompantli suggesting that many of the skulls re those of women and children which may indicate that some of the skulls belonged to people that were sacrificed.

The Huey Tzompantli discovered in Tenochtitlan is one of the most important Aztec-related discoveries in recent times, as it sheds important clues onto the religious and sacrificial ideology of not only the Aztecs but other related ancient Mesoamerican cultures.

It is known that such skull towers were common among many Mesoamerica Cultures. However, the one discovered in Tenochtitlan is one of the largest ever found.

In fact, not only did Lopez de Gomora write about it, but Andres de Tapia, a Spanish soldier who accompanied Cortes on his conquest of Mexico in 1521 also saw the need to document what he had seen.

In his account, de Tapia said the rack included as many as tens of thousands of skulls “that were intricately placed on a very large theater made of lime and stone, and on the steps of it were many heads of the dead stuck in the lime with the teeth facing outward.”

According to the testimony of de Tapia, the structure was composed of tens of thousands of skulls; archeological data, however, provides a rough number ranging between 30,000 and 136,000.

Human sacrifices in pre-Columbian cultures are well documented, although their exact purpose has not yet become clear in many cases, especially since the codices where their existence is reported were written by disciples.

It is likely, in the light of the modern findings, that the skulls did not belong only to enemies of the Aztecs and, therefore, did not have a sobering function, but religious or ritualistic one. Studies of the recovered skulls show that most of the skulls of the Tzompantli were deformed–elongated?–which is a very common cultural practice in Mesoamerica through which people obtained a certain affiliation to a specific community.

As to the function, given the latest findings, the tower of skulls most likely had a religious function, related to the process of life and death. As revealed by archaeologist Raul Barrera Rodriguez, from INAH. It is this element that claims the identity of the Mexican people’s war and its center of political, religious and economic power, and the discovery can be considered as one of the most important that have occurred in the Templo Mayor.

“It is, therefore, a cult of life, not a rite of death.” The fact that the exposed skulls were placed facing the Huitzilopochtli temple probably meant that it was an offering to the deity of war, sun, human sacrifice, and the patron of the city of Tenochtitlan.

Tenochtitlan and the Tzompantli

The discovery of the massive Tzompantli at Tenochtitlan took experts by surprise. Although they expected that the skulls would belong to young male warriors, they were surprised to have found the skulls of women and children that obviously did not participate in the wars.

Before the skulls were placed onto the Tzompantli, scholars argue that the skulls were displayed publicly in other, although much smaller racks across the city of Tenochtitlan. It is noteworthy to mention that in the ancient Aztec view, death was seen as just one state that takes to the next. However, in Tenochtitlan, the Spanish Conquistadors saw in the sacrifice of the Aztecs an argument that would eventually justify their conquest. To the ancient Aztecs, the sacrifice of people was seen as aa display of barbarity and was the ideal excuse used by the Spanish to legitimize their conquest and the birth of a new society.

The Aztecs were not the only ancient Mesoamerican culture to have constructed skull towers. Other ancient cultures like the Maya and the Toltec also had similar customs where they found build skull towers as the Tzompantli from the heads of captured war enemies. However, the discoveries at Tenochtitlan point to the possibilities that other Tzompantli from the Maya or Toltecs may also have featured the skulls of women and children pointing towards a ritual meaning of the structure.