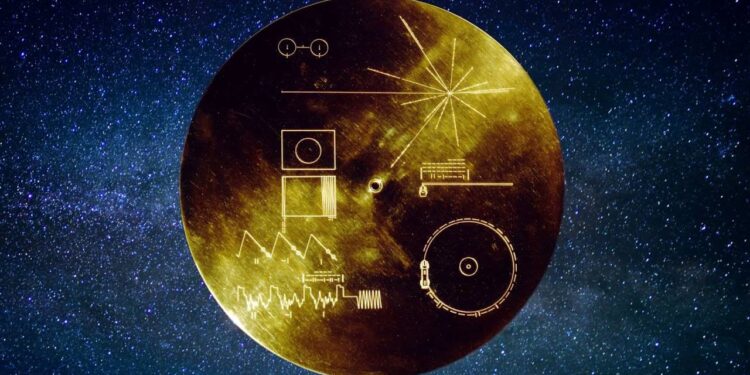

Somewhere beyond the edge of the solar system, a metal disc drifts through cold space. It is attached to a spacecraft built in the 1970s, powered by radioactive decay, and moving farther from Earth with each hour. The Voyager Golden Record is fixed to its frame. It carries no signal, emits no greeting, and was not designed to call attention to itself. But it contains a message. If another form of intelligence ever retrieves it, what they encounter will be the result of a decision made by a handful of scientists nearly fifty years ago.

A message added at the edge of the mission

The two Voyager spacecraft were designed to fly past the outer planets and then continue outward indefinitely. They were not built to return. In 1976, while the spacecraft were still under construction, astronomer Carl Sagan proposed adding a message to be carried aboard. It would not transmit. It would simply travel with the spacecraft.

NASA approved the idea and asked Sagan to lead the team. He assembled a small group, including Frank Drake, Ann Druyan, Linda Salzman, and Timothy Ferris. They were given less than six months to create a complete audio-visual record of Earth. The result would be a phonograph-style disc containing images, sounds, music, and spoken greetings.

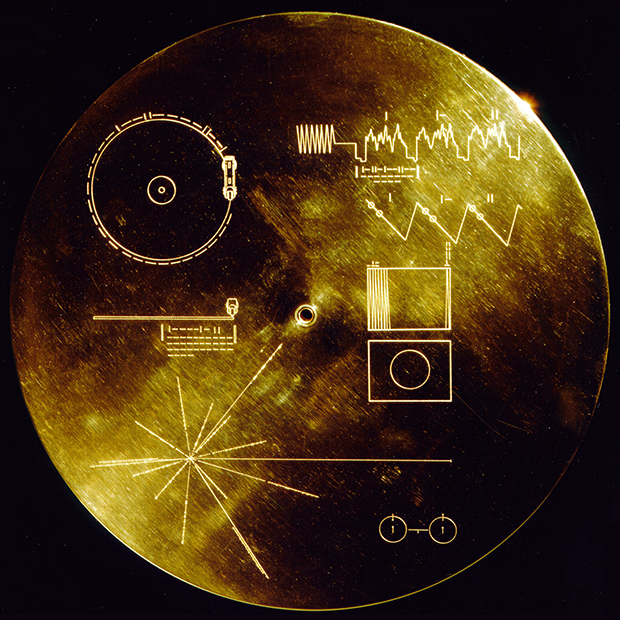

The Golden Record was made from copper, coated in gold, and stored under an aluminum cover mounted to the outside of each spacecraft. Etched into the cover were instructions for playback using universal physical constants, such as the hyperfine transition of neutral hydrogen and a diagram of 14 pulsars with their frequencies and distances. The goal was to make the contents accessible to any intelligence capable of detecting patterns in physics and mathematics.

So essentially, it was not designed to impress. It was designed to be understood. If, of course, it was ever found by an intelligent species.

What the Voyager Golden Record contains

The audio portion of the record includes 90 minutes of music from around the world. This includes classical pieces by Bach and Beethoven, traditional songs from Peru and Azerbaijan, Japanese shakuhachi flute music, and a rock and roll track by Chuck Berry. Spoken greetings in 55 languages are also included, beginning with Akkadian and ending with Wu.

The record contains 116 images encoded in analog format. These include diagrams of DNA and human anatomy, photographs of people eating, working, and giving birth, images of architecture, agriculture, and tools, and visual representations of scientific knowledge such as mathematical equations and chemical structures. One image shows a string quartet performing.

The sounds of Earth are arranged in a continuous sequence. There are recordings of waves, wind, thunder, birds, footsteps, a heartbeat, laughter, and a kiss. The greetings are short audio samples of people saying “hello” in dozens of languages.

There is a written message from then-President Jimmy Carter, who described the record as “a present from a small, distant world, a token of our sounds, our science, our images, our music, our thoughts and our feelings.” A written greeting from Kurt Waldheim, Secretary-General of the United Nations at the time, is also included.

Everything was encoded in analog format. Playback instructions were symbolic and based on physical constants, not language. The data could be recovered by constructing a stylus and following diagrams on the aluminum cover to translate the encoded waveforms into sound and images.

This is a present from a small, distant world, a token of our sounds, our science, our images, our music, our thoughts and our feelings. We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours.

— President Jimmy Carter

What we left out

The selection process was shaped by limited time, available technology, and the personal judgment of the small team involved. They chose not to include depictions of war, weapons, religious ceremonies, or political ideologies. The emphasis was on science, the natural world, and cultural variety.

The record was never meant to document a full history of civilization. Instead, it was a curated view of life on Earth during the 1970s. The exclusion of conflict was intentional. The team focused on peaceful and cooperative imagery. We are obviously not a peaceful race.

The disc includes a pulsar map that shows the Sun’s location relative to 14 known pulsars, with timing data included. While Earth is not labeled, this diagram could, in principle, allow a finder to determine the Sun’s position. The hydrogen transition diagram provides a universal reference for time and frequency. The communication relies on physics rather than language, with the assumption that any species capable of finding and decoding the record would understand these basic constants.

A message unlikely to be received

Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are not directed toward any specific star. Their final trajectories were set by gravity-assisted flybys during their planetary missions. Voyager 1 is moving toward the general vicinity of Gliese 445, a star in the constellation Camelopardalis. It will take more than 40,000 years to pass near it.

By that time, both spacecraft are expected to remain largely intact. In the vacuum of interstellar space, they are protected from heat, corrosion, and moisture. The main risks are occasional micrometeoroid impacts and high-energy radiation, but these are rare. The Golden Record, made from gold-plated copper and sealed beneath an aluminum cover, was designed to endure for over a billion years.

The disc contains no beacon or transmission system. It emits no signal. Any chance of discovery depends on another civilization detecting the spacecraft, retrieving it, examining its surface, and interpreting its contents. Playback would require only mechanical tools and an understanding of basic atomic physics. So this message of ours travels without a destination or announcement.

Earth in the 1970s, sealed in metal

The Voyager Golden Record captures a brief and specific moment in the late 1970s. Its music was selected by a small group working with limited time and resources, drawing from recordings they could access quickly. The imagery reflects the technological and cultural context of the United States, where the project was produced, though the subjects depicted were intended to represent human life more broadly.

All content was encoded in analog format. There are no digital files, no internet-era symbols, and no references to artificial intelligence, climate science, or orbital technology. The record presents Earth as it was seen through the lens of mid-20th-century science and optimism.

Among the more personal inclusions is a one-hour EEG recording of Ann Druyan’s brain activity. She prepared for the session by focusing her thoughts on the history of life on Earth, human relationships, and her feelings for Carl Sagan. The brainwave patterns were translated into audio data and included without annotation.

Today, the record remains attached to both Voyager spacecraft, drifting beyond the edge of the solar system. It contains no updates, no annotations, and no explanation beyond the diagrams etched into its cover. It reflects the judgment of a small team who made selections quickly, without consultation from international bodies. They worked with the materials and time they had, choosing content they believed would be understandable, non-threatening, and representative of life on Earth at that moment.

Would we send the same message today?

If a similar message were proposed today, the process would likely involve more people, more discussion, and more time. The content might include digital formats and modern symbols. Selections would be debated, and questions of representation, language, and purpose would likely shape the result.

In 1977, the team worked quickly. They had a few months to make decisions and prepare the materials. There was no global consultation or institutional review. The record was assembled under deadline, with content chosen by a small group based on what they could access and agree upon.

Voyager 1 is now more than 24 billion kilometers from Earth. It continues to respond to commands, although some instruments have stopped functioning. Voyager 2 is traveling on a different trajectory, farther behind. Both spacecraft carry identical copies of the Golden Record.

The discs remain bolted to the mainframes of the spacecraft, shielded by aluminum covers. They do not transmit or guide. They drift outward on trajectories set decades ago. Their path is not aimed at any destination. Whether the message will ever be found is unknown. It remains there, attached to a spacecraft in motion, recorded in analog, and built to persist.