Around 13,000 years ago, before the invention of technologies such as the wheel, the pulley, pottery, and metallurgy, and even before writing, a long-lost civilization in present-day Turkey built one of the most amazing multi-tun structures in the world.

There is a fascinating archaeological site located in the southeastern Anatolia region of Turkey. It is called Göbekli Tepe, and it promises to redefine our understanding of history, megalithic buildings, and early societies.

Built during a time when technologies such as the pully or the wheel were not even invented, Göbekli Tepe’s builders are thought to have been no more than hunter-gatherers.

To me, calling the builders of Göbekli Tepe undeveloped hunter-gatherers, who happened to somehow build one of the most impressive temples in the history of humankind, is an insult to the history of civilization.

These people were more than ordinary hunter-gathers. They were advanced in every sense. Had they not been, they would not have been able to construct a megalithic complex of such proportions.

Göbekli Tepe is massive. In fact, it is so large that although archeological excavations have been well underway for more than two decades, we’ve barely scratched the surface, exploring a little over five percent of the site. This means that around ninety-five percent of Göbekli Tepe remains buried beneath the surface.

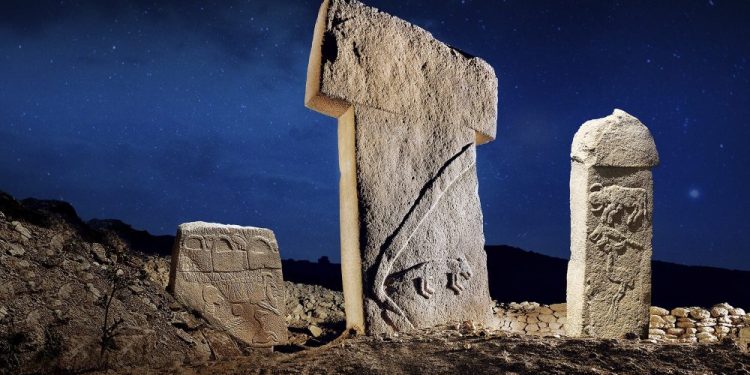

So far, archaeological surveys have revealed more than 200 stone pillars intricately placed in 20 circles. The fascinating part is the size and weight of the pillars. According to experts, each pillar has a minimum height of six meters, with a weight averaging ten tons.

These pillars were fitted into sockets that were hewn out of the local bedrock.

The exact purpose of the massive pillars and the entire complex remains a mystery, despite archaeological fieldwork being carried out on the site since 1996.

Even though we have barely scratched the surface of Göbekli Tepe, what we have found so far attests to various centuries of activity, beginning at least as early as the Epipaleolithic period–between approximately 20,000 and 10,000 years Before Present (BP).

This entire complex of stones, pillars, and sculptures were deliberately buried around 8000 BC for a reason we have still not understood.

Scholars argue that, together with Nevali Çori, this site has revolutionized the Eurasian Neolithic understanding.

It contains the oldest megalithic complex known to date, built six thousand years before Stonehenge. It is considered the oldest temple or sanctuary in the world, where “the consciousness of the sacred” was likely birthed, playing an important role in the spark that would eventually give rise to civilization as we know it.

Archeological fieldwork has identified three phases of occupation, or three layers: Layer III–the oldest–, Layer II and Layer I.

Layer III designates the oldest occupation level and is believed to date back all the way to the Pre-Ceramic Neolithic A (PPNA), around 9000 BC. During this time, the builders quarried and raised the massive pillars and linked them via walls that form circular or oval constructions. It is believed that during this time, the builders erected more than 20 intricate structures with massive pillars in their center.

The massive stone slabs were transported from bedrock pits found around 100 meters (330 ft) from the hilltop, and the builders used flint points to cut and shape the limestone bedrock. It is an incredible achievement for ancient cultures to have cut, quarried, and transported massive multi-ton blocks of stone more than 11,000 years ago.

Layer II, dated to the Pre-Ceramic Neolithic B (PPNB), between 7500-6000 BC, revealed several adjacent rectangular rooms with polished lime pavements, reminiscent of the opus signinum floors of Ancient Rome.

One of the most curious pillars was discovered at Göbekli Tepe in 2010, dating back to the PPNB; it is a stone pillar reminiscent of totem pole designs, measuring 1.92 meters in height, and resembles the totem pols commonly found in North America.

The pillar features three traits on its surface, the uppermost of which represents a predator, most likely a bear. Beneath, it features a humanoid shape. Regrettably, the pillar is damaged, making understanding its symbols challenging.

Curiously, similar pillars were also discovered at Nevali Çori.

But many of the symbols at Göbekli Tepe carry a message. Its monoliths are decorated with carved reliefs of animals and abstract pictograms.

These pictograms may represent what is usually interpreted as sacred symbols, similar to those painted in Neolithic caves around the globe.

These carefully sculpted figurative reliefs depict lions, bulls, wild boars, foxes, gazelles, donkeys, snakes, other reptiles, insects, arachnids, and birds, especially vultures.

When the sanctuary was built, the surrounding environment was probably much lusher than today, supporting a wide variety of wildlife; this was before the many millennia of human settlements. Agriculture turned it into the arid region we see today.

Vultures are also characteristic of the iconography of other Neolithic sites such as Çatalhöyük and Jericho; Researchers assume that in the early Neolithic cultures of Anatolia and the Near East, the deceased were deliberately exposed to the open air so that they could be emaciated by vultures and other raptors.

The head of the deceased was sometimes separated from the body and preserved apart, perhaps as a sign of ancestor worship.

This could represent an early form of open burial, as still practiced today by Buddhists in Tibet and India.

All conclusions about Göbekli Tepe, drawn until now, are considered preliminary since we have not fully excavated the site.

Given that we’ve only managed to reveal around five percent of Göbekli Tepe, it is likely that many generations of archeologists will work to reveal the site in the future fully.

The discovery will potentially help rewrite the history of humankind and the very origin of civilization, revealing a long-lost culture of megalithic builders.

Layer I of Göbekli Tepe is the uppermost part of the hill. Although the shallowest, experts say it accounts for the longest stretch of time.

Around 8,000 BC, the massive megalithic complex was buried under debris. The exact reason why the builders chose to hide Göbekli Tepe remains one of the site’s greatest mysteries.

Join the discussion and participate in awesome giveaways in our mobile Telegram group. Join Curiosmos on Telegram Today. t.me/Curiosmos